AbstractConsistent alignment of capabilities and internal processes with the customer value proposition is the core of any strategy execution.

Robert Samuel Kaplan

Emeritus Professor of Leadership Development, Harvard Business School

One of the most valuable resources a company owns is the "portfolio of value propositions" to its diverse external stakeholders, such as customers, investors, and resource owners. In this article, we fill a gap in the value proposition literature by identifying features that make the value propositions of new companies different from other resources, along with factors that make them valuable. A value proposition is conceived as being what enables and improves business transactions between a new company and external stakeholders. We reason that two features in particular make value propositions of new companies distinct: (1) business transactions between a new company and one or more external stakeholders, and (2) investments to create and improve a new company's value propositions that enable business transactions. We provide a definition of "value proposition" and postulate that a value proposition will benefit a new company when it: (1) strengthens the new company's capabilities to scale; (2) increases demand for the new company's products and services; and (3) increases the number, diversity, and rapidity of external investments in the new company's value proposition portfolio.

Introduction

We focus in this paper on value propositions for external stakeholders created by new companies that are committed to scale, that is, to growing the amounts they are worth rapidly. For example, a company that grows its value from $0 to $1 billion in less than ten years is a company that scaled. Scaling company value is the guiding principle that these focal companies use to manage their internal affairs, as well as their interactions with external stakeholders. For these new companies, the value propositions that matter most are those that help them scale, and value proposition portfolios for their stakeholders are their most valuable assets.

The purpose of this article is to identify (1) features that make a value proposition for an external stakeholder different from other new company resources, and (2) factors that make a value proposition beneficial to a new company committed to scale.

Important contributions have been made to improve our understanding of the value proposition concept since it was first introduced in 1983 (Lanning & Michaels, 1988; Lanning, 2020). While these contributions have been widely discussed and cited (Goldring, 2017; Payne et al., 2017; Eggert et al., 2018; Wouters et al., 2018; Payne et al., 2020), we find it difficult to understand what the features are that make a value proposition distinct from other company resources, what the factors are that make a value proposition for external stakeholders valuable, and how new companies that wish to scale can cost-effectively develop, communicate, and deliver value propositions.

Most of the extant research on value propositions focuses on established companies, rather than new companies committed to scale. These studies implicitly assume that a company that can invest in refining or enhancing its value propositions already has an established customer base, distribution channels, knowledge of the markets, and efficient business relationships with suppliers, investors, and other external stakeholders. However, the reality that new companies face when developing value propositions is far messier, particularly what is faced by those new companies that are capital-asset light (they own no or only a few assets), and yet still wish to scale their company value rapidly.

In addition to the challenges that new companies face to access, combine, deploy, and align internal and external resources (Bussgang & Stern, 2015; Kaartemo et al., 2018; Clough et al., 2019), they have to convince a diverse set of external stakeholders that the company’s value propositions will benefit them over the short-, medium- and long-term. The context of new companies committed to scaling thus requires a better understanding of what is special about the value proposition concept, and what factors affect the value of a value proposition.

New companies committed to scale need to operate across borders, innovate relentlessly, profitably adopt emerging technologies, and execute capital investment programs that enable them to meet aggressive growth objectives. The successful operations of such companies depend on their constructive engagement with multiple external stakeholder groups. Each stakeholder group has unique needs and objectives. The multiplicity of critically relevant external stakeholders necessitates the formulation of multiple valuable propositions that target very different groups with dissimilar roles, needs, and priorities.

Managing a “portfolio of diverse value propositions” requires the development of company capabilities that can configure internal and external resources in a way to deliver promises made to the different external stakeholders, as well as achieve the objectives of the company’s master scaling plan. New companies that wish to scale rapidly require value proposition development capabilities that go beyond the ones required by companies that have small or moderate growth objectives. Diverse value propositions, all having a logic to scale early and rapidly since inception, must be developed. Each value proposition must then be aligned with the value propositions of all other key stakeholders, as well as with the new company’s pathway to scale.

Most of the resources that an asset-light company uses to scale rapidly at early stage of its development are owned by external organizations. Quite often, these new companies develop value propositions for investors and resource owners before they operationalize customer value propositions. Most companies that manage to scale rapidly advocate shaping their investor value propositions as much as they advocate their customer value propositions. Clearly a multiple external stakeholder approach to value proposition development, communication, and delivery is required, rather than just an approach that focuses predominantly on customer value propositions and related customer transactions.

An implicit assumption of our research is that one of the most valuable resources (perhaps the most valuable resource) that a new asset-light company owns is its portfolio of value propositions to diverse external stakeholders. Yet, the conceptualization of what makes a value proposition itself valuable has received little attention in the literature.

In response to this, the article is organized as follows. We first identify the gap in the literature that later we attempt to fill. Next, we identify features that make a value proposition distinct for an external stakeholder, as well as insights gained from examining the “elemental version” of a value proposition. Following this, we identify factors that influence the benefits of value propositions. We then close with some conclusions.

2. Literature Gap to be Filled

At least five excellent reviews of the literature on value propositions have been published in the last three years (Goldring, 2017; Payne et al., 2017; Eggert et al., 2018; Wouters et al., 2018; Payne et al., 2020).

The extant literature provides at least seven constitutive perspectives on value propositions. A value proposition has been conceptualized as a:

1. Component of a business model (Johnson et al., 2008; Zott et al., 2011; Coombes & Nicholson, 2013; Goyal et al., 2017).

2. Narrative that describes the compelling reasons to buy products and services (Moore, 2002; Blank, 2007; Payne et al., 2017).

3. Promise of value creation that builds upon a configuration of resources and practices (Lusch & Vargo, 2006; Kowalkowski, 2011; Chandler & Lusch, 2015; Skålén et al., 2015; Vargo, 2020).

4. Framework to enhance the effectiveness of customer value creation and communication processes (Lanning & Michaels, 1988; Lanning, 2000; Webster, 2002; Anderson et al., 2007; Barnes et al., 2009; Osterwalder et al., 2014; Barnes et al., 2017; Dennis, 2018).

5. Market shaping device and customer contextualization strategy (Kumar et al., 2000; Holttinen, 2014; Kindström et al., 2018; Spinuzzi et al., 2018; Nenonen et al., 2019; Nenonen et al., 2020).

6. Process to address strategic and implementation concerns (Payne et al., 2020).

7. Mechanism to engage multiple stakeholders for developing market offers (Grünbacher et al., 2006; Ballantyne et al., 2011; Frow & Payne, 2011; Truong et al., 2012; Baldassarre et al., 2017; Eggert et al., 2018).

One of the constitutive perspectives on value propositions argues that conceptualizing value needs to take place in a multiple stakeholder setting, rather than just being embedded in a single stakeholder setting (for example, customers). We argue however that the adoption of a multiple stakeholder perspective can result in explicitly formulating value propositions for all relevant stakeholders, and not just a few stakeholders on company’s customer value proposition development. We find this emphasis significant in practice and believe that companies failing to realize its importance are likely bound to continuously struggle in pursuing a scaling path.

This should be taken into consideration while keeping in mind that value creation in industrial markets, “usually involves many companies and other actors where the links between them are interdependent and project tasks are not completely controlled by any one of them” (Ballantyne et al., 2011). It seems to imply the need for “a shift in a company’s strategic point-of-view to recognize the network of relationships in which they and their customers, suppliers, other institutions and their respective employees are embedded” (Ballantyne et al., 2011).

Payne, Ballantyne, and Christopher (2005), Frow and Payne (2011) and Ballantyne et al. (2011), all adopted a relational framework of six stakeholder groups to develop a value proposition. Ballantyne et al. (2011) proposed a process for shaping reciprocal value propositions that requires an initiator who can develop a provisional yet reciprocal view of what might be of value to the focal company, along with each of its most relevant counterparts. The process is enabled through workshops that bring both sides into one shared communicative framework. The initiator role of the process does not need to be credited or attached to a single stakeholder group. This reciprocity in value proposition development allows for innovating and optimizing the implementation of the process in specific contexts to meet diverse stakeholder needs.

Eggert et al. (2018) also emphasize the need to adopt a multiple stakeholder perspective for value proposition development in business-to-business (B2B) companies. They argue that, (1) business value should be conceptualized in an ecosystem perspective by understanding the complex network of relationships and “how these relate to the idiosyncratic value of an individual actor”, (2) there is a need to better understand how value propositions at various levels of granularity are linked together, and (3) business-to-business companies should develop multiple value propositions to reflect increasing levels of personalization for their clients and customers (Eggert et al., 2018).

We thus extracted two important lessons from our study of value propositions literature to highlight in this section: (A) Value proposition development efforts need to focus on multiple external stakeholders, rather than just on a single set of stakeholders, likely customers, and (B) Engaging reciprocally with all relevant actors enables the shaping of mutually beneficial value propositions and the development of new market offers (Grünbacher et al., 2006; Ballantyne et al., 2011; Frow & Payne, 2011; Truong et al., 2012; Baldassarre et al., 2017; Eggert et al., 2018).

One of the conclusions that can be drawn from engaging multiple stakeholders to develop value propositions is the existence of a need for aligning these propositions both with each other and with the new company’s scaling objectives. Unfortunately, theoretical approaches have not been proposed so far to address this need.

Martinez and Bititci (2006) offered one of the few studies that has examined the alignment of multiple value propositions among supply chain members in an industry. Their in-depth case study focused on the fashion industry, showing that: (i) the strategic members of a supply chain are those who hold the chain’s core competencies; (ii) the value propositions of a supply chain’s strategic members dictate its overall value proposition; (iii) the value propositions of the supply chain’s strategic members should be aligned to enhance its overall value proposition; (iv) if regular (not-strategic) members of the supply chain have value propositions that go beyond the needs of the supply chain, they should nevertheless support its overall value proposition; (v) the value proposition of the overall supply chain is the same as that of the company that is facing the end customer; (vi) the alignment of supply chain members’ value propositions with the overall supply chain’s value proposition ensures the alignment of strategic competencies; and (vii) strategic members collaborate to improve the supply chain’s competencies. However, the Martinez and Bititci (2006) findings do not apply to the case of new companies committed to scaling, which is what we have chosen as the main focus of this paper.

3. Key Features of a Value Proposition

The purpose of this section is to identify key features that make a new company’s value proposition different from other company resources.

We apply the logic used to identify what makes multisided platforms special by Haigu and Wright (2015), along with the “elemental version” approach to formalize insights from various theories of the firm used by Gibbons (2005), to argue that at the most fundamental level, a new company’s value proposition has two key features that make it distinct:

1. Business transactions: a value proposition enables a new company and an external stakeholder to directly interact via transactions between one another without the need of an intermediary.

2. Investment to create and improve business transactions: a value proposition attracts, both from new company owners and external stakeholders, the investments that are necessary to create, actualize, and improve a value proposition.

By “directly interact” between one another, we mean that the company and the external stakeholder “retain control over the key terms of the interaction” (Hagiu & Wright, 2015). An independent third party does not control the terms of the business transaction. While we applied the same logic that Hagiu and Wright (2015) used, the business transactions and direct interactions that we are concerned about are those between the company and external stakeholders, rather than those that occur between two external stakeholders.

By “investments that are necessary to create, actualize, and improve a value proposition”, we mean the cash and in-kind (time, effort, reputation) contributions that the company and external stakeholders allocate to the development, maintenance, execution, communication, and implementation of the value proposition portfolio, which enables business transactions. These investments are tangible evidence of organizational commitments to the development and evolution of the new company’s value propositions as a way to facilitate business transactions with external stakeholders.

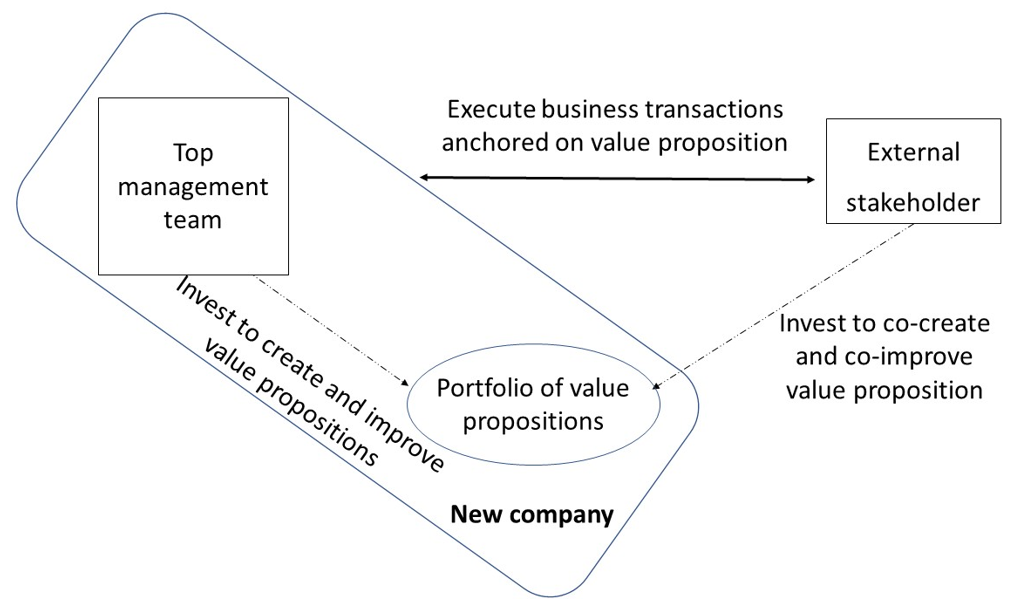

Figure 1 illustrates the elemental version of our perspective, which was inspired by Gibbons (2005). It reduces to stark simplicity what makes a value proposition special: business transactions between the new company and its external stakeholders, along with investments that create and improve value propositions.

The elemental version of our value proposition perspective applies to multiple stakeholders and incorporates what we call “reciprocal dialogues”. It highlights the need for a new company to develop two types of value propositions (1) value propositions to anchor business transactions (set prices for good and services) or investment (set company valuation), and (2) value propositions to attract external partners to make commitments to create and improve the already existing value propositions that enable business transactions (set terms for information and technology exchanges during product feature co-creation).

Figure 1 illustrates that the company and an external stakeholder execute business transactions anchored on an existing value proposition. For example, a customer value proposition enables transactions between the company and a customer for the purpose of the sale/purchase of goods and services. Each side retains control over the terms of the transaction. These terms may involve price, quality, delivery, timing, levels of service, and so on. Setting the terms of a transaction may take place before, during, and after the sale/purchase.

The external stakeholder could also be an investor, resource owner, partner, etc. In the investor’s case, an investor value proposition enables business transactions between the company and the investor. The company and the investor both retain control of the terms of the business transactions.

A value proposition is thus the outcome of a reciprocal process that takes place between a company and one or more of its external stakeholders. The formulation and implementation of a reciprocal process leading to the creation and improvement of a value proposition requires both the company and the external stakeholder to invest. These combined investments both maintain and enhance their commitments to one another. The investments are necessary for the two parties to be able to carry out business transactions with each other. For example, product co-creation requires that both company and customer invest money, time, effort, and reputation to produce the customer value proposition that anchors or will anchor their business transactions. Similarly, the preparation of a funding agreement, due diligence, and so on, requires the new company and investor to make cash and in-kind investments to develop an investor value proposition, and thus to anchor their business transactions. Lastly, the acquisition of any resource requires that the company and resource owner co-invest to create and improve the resource-owner value proposition that will anchor their direct transactions.

Figure 1. Elemental version of a value proposition

4. Insights about Elemental Versions of Value Propositions

Definition of value proposition

We define a value proposition as follows, based on our conceptualization of the two features that make it distinct:

A company’s value proposition makes explicit how a stakeholder and the company benefit from, (1) completing transactions with each other, and/or (2) improving how (the process by which) these transactions are completed.

Two classes of value propositions

A new company that wishes to scale rapidly needs to engage multiple stakeholder groups with value propositions. These propositions can be organized into two classes: (1) value propositions to carry out business transactions (for example, customer value propositions for the sale of goods and services; investment value propositions for funding rounds, resource owner value propositions for capital leases), and (2) value propositions for external stakeholders to invest in the development and improvement of the value propositions for business transactions.

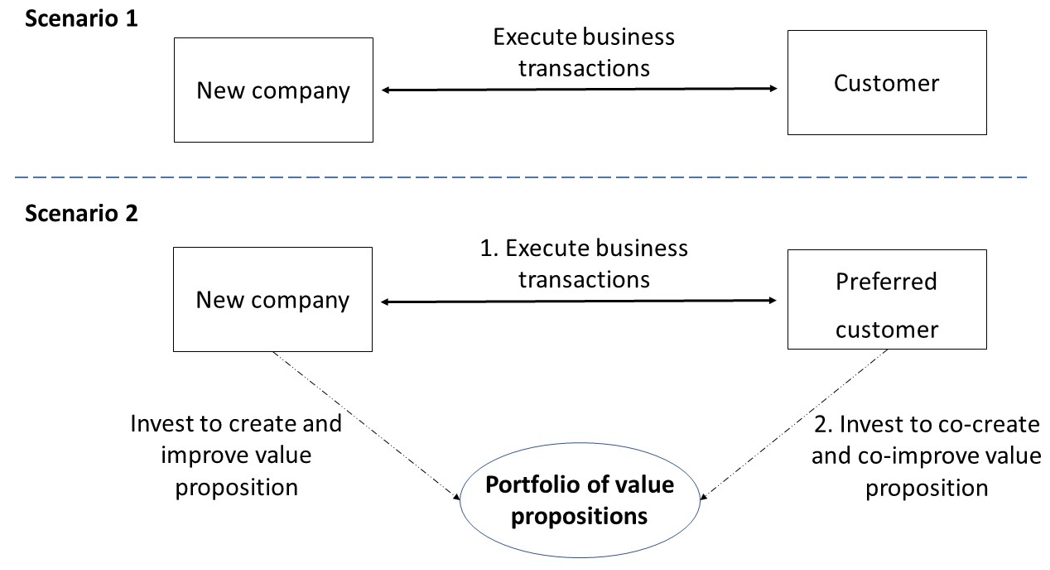

Consider two possible scenarios for the experience between a new company and a customer. Note that the logic used in this example also applies to other external stakeholder groups such as investors and resource owners.

In Scenario 1, the experience is that of a business transaction, which has been defined by a value proposition known to both parties.

In Scenario 2, the business transaction experience has been defined by a value proposition co-created by a customer and the new company. The customer has a “preferred customer” status because it is investing to work with the new company in order to create and improve one or more value proposition for business transactions.

The Scenario 2 preferred customer experience can be viewed as having two parts: the business transaction experience, and the investment experience. One outcome of the investment experience is co-developing or co-improving the value propositions that define the experience for all customers carrying out business transactions.

Preferred stakeholders are stakeholders that invest to co-create and co-improve the new company’s value propositions. Therefore, for each preferred stakeholder the new company holds two different value propositions; one that enables business transactions, and the other that attracts investments to create and improve value propositions.

Consider two portfolios of value propositions for external stakeholders. The first portfolio is comprised of five value propositions that were developed by the new company’s founders working in isolation. The second portfolio is comprised of five value propositions that were co-developed by the founders working with preferred stakeholders. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the second portfolio is more valuable to more people than the first.

Figure 2 illustrates the two scenarios identified above. It shows that new companies and their customers carry out business transactions in both scenarios. These transactions are anchored in a tested and validated customer value proposition. In Scenario 1, the new company and the customer use a predefined value proposition to complete a business transaction. In this example, the new company sets a price that meets the customer’s willingness to pay, reduces the buying cost by streamlining the buying process, mitigates opportunities for resistance, and reduces the transaction’s pain points. The customer in Scenario 1 evaluates the value of the purchase, accepts the price, and pays the buying costs.

In Scenario 2, both the preferred customer and the new company invest to co-create and co-improve the value proposition that defines the business transaction experience for all customers. In this scenario, the new company uses an investor value proposition to convince the customer not only to make the purchase, but also to invest in the definition and improvement of the value proposition for possible future purchases, in a way that mutually enhances the business transaction experiences.

Figure 2. Two value proposition classes

Figure 2 illustrates a customer’s perspective when assessing a new company’s prospective offer to them. The customer needs to answer two questions: (1) Is the value of the offer worth the price?, and (2) What investment in the new company that provided the valuable offer is required for it to continue to deliver an offer that provides value we want?

Wouters, Anderson, and Kirchberger (2018) examined technology startups that are in the process of shaping customer value propositions for large established companies. They found that companies “needs to screen a large number of potential startups and assess each time: What is the value of the startup’s offering to our business, and what resources and support will the startup need so we can actually obtain its offering?”(p. 101). The authors recommend that startups should construct two value propositions for each large customer, that include (i) an Innovative Offering Value Proposition (IOVP), and (ii) a Leveraging Assistance Value Proposition (LAVP). The IOVP communicates how the startup’s market offer creates superior value for the customer than what they currently get. The LAVP conveys what the customer firm, in a B2B scenario, will receive in return for providing support and resources to the startup.

Attracting investment to create and improve the new company’s value propositions

A prospective stakeholder needs to spend effort to ensure that it will receive the benefits it requires from a new company. New companies meanwhile need to develop, communicate, and deliver value propositions that compel stakeholders to spend their cash, time, and effort helping them to define suitable value propositions as a way to anchor their business transactions. Literature that focuses on ways to attract stakeholders to invest in co-creating and co-improving new company’s value propositions is so far not well developed.

The few articles published on how improve the relationships with customers suggest that new companies’ customer value propositions should offer to: (1) provide preferred status (Bemelmans et al., 2015; Schiele et al., 2012), (2) allocate better resources, and deliver products and services first in case of production problems (Steinle & Schiele, 2008; Schiele et al., 2011), (3) help customers design their products (Cramer, 2019), (4) reduce costs and charge lower prices (Hald et al., 2009; Nollet et al., 2012), (5) provide accurate and up-to-date information (Ishengoma & Lokina, 2017), (6) help increase the perception that their customer is mature and responsible in managing supplier relationships (Bemelmans et al., 2015), and (7) shorten the lead time needed for execution (Ulaga, 2003; Christiansen & Maltz, 2010)

Value proposition co-creation

Consider the null-set situation where a new company’s portfolio of value propositions is empty, that it includes no value propositions. Assume that the division of a large company and the new company in question are collaborating in the design and development of a product that a foreign division in that large company may purchase. In this case, both the new company and the large company are investing to co-create a value proposition that works for both parties. They are not engaging in the transaction for the standard purpose of selling or purchasing goods and services. Thus, the outcome of their investments will include a unique customer value proposition that anchors direct business transactions between the new company and the large company’s foreign division.

Adding a value proposition to existing portfolio

Now examine a case where a new company’s portfolio of value propositions includes 10 value propositions for diverse stakeholders, including customers, investors, power users, resource owners, etc. Next assume that the new company and a venture capital firm invest to co-create a new value proposition that will anchor their business transactions.

The development, communication, and delivery of the new investor value proposition will have to consider the needs of key organizations that are part of the investor’s and new company’s network. To these needs, they will align the 10 value propositions from the portfolio, thereby helping achieve the new company’s scaling objectives.

5. What Makes a Value Proposition Valuable?

The purpose of this section is to identify factors that make a value proposition beneficial to a new company ex-ante (that is, the value proposition’s benefit is based on anticipated new outcomes, not results from past performance).

We postulate that three factors influence the ex-ante benefit of a value proposition. A value proposition will benefit a new company committed to scale its worth rapidly when it:

1. Strengthens the new company’s capabilities to scale (Cepeda & Vera, 2007; Lindgren et al., 2009).

2. Increases demand for the new company’s products and services (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

3. Increases the number, diversity, and rapidity of investments in the conceptualisation, development, maintenance, and refinement of value propositions for external stakeholders (Emerson, 2003; Frow & Payne, 2011; Bussgang & Stern, 2015)

The remainder of this section provides a set of statements of what a new company can do to increase the benefit of its value propositions for the purpose of growth and scaling. Some of the collected statements below are based on insights emerging from existing literature, while others are based on insights that come from a team of experienced practitioners associated with our research project.

Strengthen capabilities to scale

1. Attract individuals who have the requisite experience and knowledge to increase the spread between customers’ willingness to pay for a product and the cost of the product (Emerson, 2003; Schmidt & Keil, 2013; Banker et al., 2014; Bussgang & Stern, 2015).

2. Most significant stakeholder benefits should be quantified in specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time bound terms (Barnes et al., 2009; Hudson, 2017; Eggert et al., 2018).

3. Use an end-to-end (E2E) solution that links procurement directly with end customers, in order to eliminate or reduce inventory and the number of intermediaries between the company and customers (Walters & Lancaster, 2000; Rodriguez et al., 2008).

4. Customize ideal next steps to coordinate activities between new company and customers (Buttle, 1999; Ballantyne et al., 2011).

5. Digitize as much of your company as you can to create value for customers, reduce costs, and increase security (Hervé et al., 2020: Westerlund, 2020).

6. Build internet-based capabilities to acquire and retain customers, investors, and owners of resources required to scale (Ordanini & Rubera, 2008).

7. Learn from value propositions of companies that have scaled early, rapidly, and securely, and use them to differentiate your company (Bussgang, 2015).

8. Increase the value chain’s competence(Walters & Lancaster, 2000; Carlucci et al., 2004).

9. Access, combine, and deploy resources required to create value and scale, by providing all external resource owners with returns they cannot gain on their own (Melancon et al., 2010; Girotra & Netessine, 2013; 2014; Bussgang & Stern, 2015).

10. Deploy combinations of resources that will create value that exceeds the sum of the value created from each resource separately (Bititci et al., 2004; Tantalo, & Priem, 2016).

11. Articulate a compelling image of your future company, using it to convince investors to provide funding, and resource owners to provide resources needed to scale the business (Dennis et al., 2007; Park et al., 2010; Davidsson, 2015).

12. Align your most valuable resource configuration with your master scaling plan (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Bailetti & Tanev, 2020).

13. Enable customers, users, investors, and others to automatically extract information from company data for the purpose of decreasing costs and adding value to stakeholders (Dawar, 2016).

14. Apply big data analytics to produce insightful information about users, suppliers, and customers (Schermann et al., 2014; Elia et al., 2020).

Increase demand

1. Grow customers' willingness and ability to directly interact with the new company for the purpose of consuming its products and services (Lindič & da Silva, 2011; Berman, 2012).

2. Adapt value propositions to changes in customer segments (Kowalkowski, 2011; Payne et al., 2017).

3. Use data and artificial intelligence to personalize offers to consumers (Pires et al., 2006).

4. Constantly monitor customers’ buying habits and deliver offers that are convenient, cater to customer demands, are secure, and offer excellent customer experiences (Fifield, 2007; Blocker, 2011).

5. Deliver better performance on the metrics that customers care about (Kowalkowski, 2011; Ling-Yee, 2011).

6. Define the ideal target customer profiles and engage them relentlessly (Anderson et al., 2006; Osterwalder et al., 2014).

7. Continuously improve value propositions based on results and feedback (Ballantyne, & Varey, 2006; Payne & Frow, 2014).

8. Listen to your customers, take their feedback seriously, and adjust operations as needed (Hardy, 2005; Walker, 2008).

Increase investments to enable direct interactions

1. Adopt a stakeholder-centric approach to satisfy the expectations of customers, investors, resource owners, and other important actors, as required to scale (Frow & Payne, 2011; Lusch & Webster, 2011; Corvellec & Hultman, 2014; Bailetti & Tanev, 2020)

2. Establish a position in external networks that increases stakeholders’ investments to improve the volume, variety, and velocity of direct interactions with the new company (Bititci et al., 2004; Windahl, & Lakemond, 2006; Schmidt & Keil, 2013).

3. Develop value propositions for key members of the value chain that align with other key members’ value propositions, as well as improving the overall competence of the value chain (Flint, & Mentzer, 2006; Martinez & Bititci, 2006; Frow et al., 2014).

4. Engage customers to produce testimonials, reviews, and ratings that help new customers to make purchasing decisions with knowledge of other customers’ experiences (Payne et al., 2008; Saarijärvi, 2012).

5. Collaborate with the company’s value chain to determine optimal offers that achieve customer fulfillment and enhance customer value (Martinez & Bititci, 2006).

6. Establish trust and positive rapport with your customers that nurtures long-term, mutually beneficial business relationships (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2003; Capon & Hulbert, 2007).

7. Attract great people with high customer and high growth orientation (Frow & Payne, 2011; Pandita, 2011; Nyman & Stamer, 2013).

8. Always think from your customer’s perspective both organizationally and personally (Capon & Hulbert, 2007; Buttle, 2019).

9. Track changes in stakeholders’ value propositions and use the information to realign the value propositions (Baldassarre et al., 2017).

6. Conclusion

The delivery and improvement of value propositions to external stakeholders is what determines whether a new company operates as a functional/actual business, or rather exists as an opportunity still merely wanting to become a business.

In this paper, we have attempted to fill a gap in the literature by examining the features that make a value proposition distinct from other new company resources, along with the factors that make it valuable or beneficial to a company. We framed the “portfolio of value propositions” for external stakeholders as one of the most important resources a new company holds. This portfolio aligns value propositions to one another, as well as investments to a new company’s scaling objectives. Marketable value propositions are a key source of competitive advantage for a new company.

New companies committed to scaling their business rapidly must design, communicate, and implement value propositions for diverse external stakeholders. Two features make these value propositions distinct: (1) value propositions anchor business transactions between the new company and external stakeholders, and (2) value propositions attract external stakeholder investments to create and improve the value propositions portfolio.

A value proposition will benefit a new company when it: (1) Strengthens the new company’s capabilities to scale; (2) Increases demand for the new company’s products and services; and (3) Increases the number, diversity, and rapidity of external investments in the conceptualisation, development, maintenance, and refinement of value propositions for external stakeholders.

The presence of preferred stakeholders combined with the continuous creation of new value propositions, along with improvement of existing value propositions, can add significant value to a new company’s value propositions portfolio.

We suggest that future research should focus on identifying dynamic capabilities that support a new company’s scaling activities, how to improve value propositions by interacting with preferred stakeholders over time, and features that make each of the identified seven perspectives above regarding value propositions distinct. In addition, future research should explicitly explore the attributes of business transactions that enable scaling company value in the near-, mid-, and longer-term. A more detailed exploration of business transactions in the context of new companies willing and attempting to scale rapidly and securely would also require differentiating between ex-ante and ex-post company value, as well as identifying clear-cut criteria about what makes certain transactions into value-adding mechanisms for a new company that wishes to scale.

References

Anderson, J.C., Kumar, N., & Narus, J.A. 2007. Value Merchants: Demonstrating and Documenting Superior Value in Business Markets. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Anderson, J., Narus, J. & Van Rossum, W. 2006. Customer value propositions in business markets. Harvard Business Review, 84(3): 91-99.

Bailetti, T. & Tanev, S. 2020. Examining the relationship between value propositions and scaling value for new companies. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(2): 5-13. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1324

Baldassarre, B., Calabretta, G., Bocken, N. & Jaskiewicz, T. 2017. Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: A process for sustainable value proposition design, Journal of Cleaner Production, 147: 175-186.

Ballantyne, D., Frow, P., Varey, R., & Payne, A. 2011. Value propositions as communication practice: Taking a wider view. Industrial Marketing Management, 40: 202-210.

Ballantyne, D. & Varey, R. 2006. Creating value-in-use through marketing interaction: the exchange logic of relating, communicating and knowing. Marketing Theory, 6(3): 335-348.

Banker, R.D., Mashruwala, R. & Tripathy, A. 2014. Does a differentiation strategy lead to more sustainable financial performance than a cost leadership strategy? Management Decision, 52(5): 872-896.

Barnes, C., Blake, H. & Howard, T. 2017. Selling your value proposition. How to transform your business into a selling organization. London: Koga Page.

Barnes, C., Blake, H. & Pinder, D. 2009. Creating and delivering your value proposition: Managing customer experience for profit. London: Kogan Page.

Bemelmans, J., Voordijk, H., Vos, B. and Dewulf, G., 2015. Antecedents and benefits of obtaining preferred customer status. International journal of operations & production management.

Berman, S. J. 2012. Digital transformation: opportunities to create new business models. Strategy & Leadership, 40(2): 16-24.

Bititci, U.S., Martinez, V., Albores, P. & Parung, J. 2004. Creating and managing value in collaborative networks. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 34(3/4): 251-268.

Blank, S. 2007. The four steps to the epiphany – Successful strategies for products that win. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Enterprises.

Blocker, C.P. 2011. Modeling customer value perceptions in cross-cultural business markets. Journal of Business Research, 64(5): 533-540.

Bussgang, J. & Stern, O. 2015. How Israeli startups can scale. Harvard Business Review (September).

Buttle, F. 2019. Customer Relationship Management: Concepts and Technologies. 4th Edition. Routledge.

Buttle, F. 1999. The SCOPE of customer relationship management. International Journal of Customer Relationship Management, 1(4): 327-337.

Capon, N. & Hulbert, J.M. 2007. Capon, Noel. Managing marketing in the 21st century: developing and implementing the market strategy. Bronxville, N.Y.: Wessex Inc.

Carlucci, D., Marr, B. & Schiuma, G. 2004. The knowledge value chain: how intellectual capital impacts on business performance. International Journal of Technology Management, 27(6-7): 575-590.

Cepeda, G. & Vera, D. 2007. Dynamic capabilities and operational capabilities: A knowledge management perspective. Journal of business research, 60(5): 426-437.

Chandler, J. & Lusch, R. 2015. Service systems: a broadened framework and research agenda on value propositions, engagement and service experience. Journal of Service Research, 18(1): 6-22.

Christiansen, P.E. and Maltz, A., 2002. Becoming an" interesting" customer: Procurement strategies for buyers without leverage. International Journal of Logistics, 5(2): 177-195.

Clough, D., Fang, T., Vissa, B. & Wu, A. 2019. Turning Lead into Gold: How Do Entrepreneurs Mobilize Resources to Exploit Opportunities? Academy of Management Annals, 13(1): https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.013

Coombes, P. & Nicholson, J. 2013. Business models and their relationship with marketing: A systematic literature review. Industrial Marketing Management, 42: 656-664.

Corvellec, H. & Hultman, J. 2014. Managing the politics of value propositions. Marketing Theory, 14(4): 355-375.

Cramer, R., 2019. How to improve the relationship between buyer-supplier: A qualitative research with exploration of new methods (Bachelor's thesis, University of Twente).

Davidsson, P. 2015. Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5): 674-695.

Dawar, N. 2016. Use Big Data to Create Value for Customers, Not Just Target Them. Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2016/08/use-big-data-to-create-value-for-customers-not-j...

Dennis, L. 2018. Value propositions that sell. USA: Mind Your Business Press.

Dennis, C., King, T. & Martenson, R. 2007. Corporate brand image, satisfaction and store loyalty. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(7): 544-555. DOI: 10.1108/09590550710755921

Di Pietro, L., Edvardsson, B., Reynoso, J., Renzi, M.F., Toni, M. & Guglielmetti Mugion, R. 2018. A scaling up framework for innovative service ecosystems: lessons from Eataly and KidZania. Journal of Service Management, 29(1): 146-175. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2017-0054

Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., Frow, P., Payne, A. 2018. Conceptualizing and communicating value in business markets: From value in exchange to value in use. Industrial Marketing Management, 69: 80-90.

Elia, G., Polimeno, G., Solazzo, G. & Passiante, G. 2020. A multi-dimension framework for value creation through big data. Industrial Marketing Management, in press. ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.08.004

Emerson, J. 2003. The Blended Value Proposition: Integrating Social and Financial Returns. California Management Review, 45(4): 35-51.

Fifield, P. 2007. Marketing Strategy Masterclass: Making Marketing Strategy Happen. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Flint, D.J. & Mentzer, J.T. 2006. Striving for integrated value chain management given a service-dominant logic for marketing. The service dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate and directions, ME Sharpe: 139-149.

Frow, P., McColl-Kennedy, J., Hilton, T., Davidson, A., Payne, A. & Brozovic, D. 2014. Value propositions: A service ecosystems perspective. Marketing Theory, 14(3): 327-351.

Frow, P. & Payne, A. 2011. A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2): 223-240.

Gibbons, R., 2005. Four formal (izable) theories of the firm? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 58(2), pp.200-245.

Girotra, K. & Netessine, S. 2014. Four paths to business model innovation. Harvard Business Review, July-August: 96-103.

Girotra, K. & Netessine, S. 2013. OM Forum—Business Model Innovation for Sustainability. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 15(4): 537-544. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2013.0451

Goldring, D. 2017. Constructing brand VP statements: a systematic literature review. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 5(2): 57-67.

Goyal, S., Kapoor, A., Esposito, M. & Sergi, B. 2017. Understanding business model – literature review of concept and trends. International Journal of Competitiveness, 1(2): 99-118.

Grünbacher, P., Köszegi, S. & Biffl, S. 2006. Stakeholder Value Proposition Elicitation and Reconciliation, Ch. 7 in: Biffl, S., Aurum, A., Boehm, B., Erdogmus, H. & Grünbacher, P. (Eds.). Value-Based Software Engineering. Berlin: Springer-Verlag: 133-154.

Hagiu, A. and Wright, J., 2015. Multi-sided platforms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43: 162-174.

Hald, K.S., Cordon, C., & Vollmann, T.E. (2009). Towards an understanding of attraction in buyer-supplier relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(8): 960-970.

Hervé, A., Schmitt, C., & Baldegger, R. 2020. Digitalization, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Internationalization of Micro-, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(4): 5-17. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1343

Holttinen, H. 2014. Contextualizing value propositions: Examining how consumers experience value propositions in their practices. Australasian Marketing Journal 22: 103-110.

Hudson, D. 2017. Value Propositions for the Internet of Things: Guidance for Entrepreneurs Selling to Enterprises. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(11): 5-11. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1116

Ishengoma, E. and Lokina, R. 2017. The role of linkages in determining informal and small firms’ performance: The case of the construction industry in Tanzania. Tanzania Economic Review, 3(1-2).

Johnson, M., Christensen, C. & Kagermann, H. 2008. Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review, 51: 51-59.

Kaartemo, V., Kowalkowski, C. and Edvardsson, B., 2018. Enhancing the understanding of processes and outcomes of innovation: the contribution of effectuation to SD logic. SAGE Handbook of Service-Dominant Logic: 522-535.

Kindström, D., Ottosson, M. and Carlborg, P. 2018. Unraveling firm-level activities for shaping markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 68: 36-45.

Kowalkowski, C. 2011. Dynamics of value propositions: Insights from service-dominant logic. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2): 277-294.

Kumar, N., Scheer, L. and Kotler, P. 2000. From market driven to market driving. European management journal, 18(2): 129-142.

Lanning, M. 2000. Delivering profitable value: A revolutionary framework to accelerate growth, generate wealth, and rediscover the heart of business. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Press.

Lanning, M. 2020. Try taking your value proposition seriously - Why delivering winning value propositions should be but usually is not the core strategy for B2B (and other businesses). Industrial Marketing Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.10.01

Lanning, M., & Michaels, E. 1988. A business is a value delivery system. McKinsey Staff Paper, 41: 1-16.

Lindgren, P., Saghaug, K.F., & Knudsen, H. 2009. Innovating business models and attracting different intellectual capabilities. Measuring Business Excellence, 13(2): 17-24.

Lindič, J. & Marques da Silva, C. 2011. Value proposition as a catalyst for a customer focused innovation. Management Decision, 49(10): 1694-1708. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111183834

Ling-Yee, L. 2011. Marketing metrics' usage: Its predictors and implications for customer relationship management. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(1): 139-148.

Lusch, R. & Vargo, S. 2006. Service-dominant logic: reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3): 281-288.

Lusch, R. & Webster Jr., F. 2011. A stakeholder-unifying, cocreation philosophy for marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 31(2): 129-134.

Martinez, V. & Bititci, U. 2006. Aligning value propositions in supply chains. Journal of Value Chain Management, 1(1): 6-18.

Melancon, J.P., Griffith, D.A., Noble, S.M. & Chen, Q. 2010. Synergistic effects of operant knowledge resources. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5): 400-411. DOI: 10.1108/08876041011060693

Mishra, S., Ewing, M. & Pitt, L. 2020. The effects of an articulated customer value proposition (CVP) on promotional expense, brand investment and company performance in B2B markets: A text based analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.10.005.

Moore, G. A. 2002. Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling Disruptive Products to Mainstream Customers. Harper Business, Revised edition.

Nenonen, S., Storbacka, K. & Windahl, Ch. 2019. Capabilities for market-shaping: triggering and facilitating increased value creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00643-z

Nenonen, S., Storbacka, K., Sklyar, A., Frow, P., Payne, A. 2020. Value propositions as market-shaping devices: A qualitative comparative analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.10.006

Nollet, J., Rebolledo, C., & Popel, V. 2012. Becoming a preferred customer one step at a time. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(8): 1186-1193.

Hardy, J. 2005. The Core Value Proposition. Trafford Publishing.

Nyman, A., & Stamer, M. 2013. How to attract talented software developers: Developing a culturally differentiated employee value proposition. Master’s thesis, Linköping University, Department of Management and Engineering, Industrial Economics. Linköping University, The Institute of Technology: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A668101&dswid=5141

Ordanini, A. & Rubera, G. 2008. Strategic capabilities and internet resources in procurement: A resource‐based view of B‐to‐B buying process. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(1): 27-52. https://doi-org.proxy.library.carleton.ca/10.1108/01443570810841095

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., Smith, A. & Papadakos, T. 2014. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. 2003. Modeling value propositions in e-Business. Proceedings of the 5th international conference on Electronic commerce: 429-436.

Pandita, D. 2011. The Employee Value Proposition-A Key to Attract Performers. SAMVAD, 3: 56-61.

Park, J., Sarkis, J. & Wu, Z. 2010. Creating integrated business and environmental value within the context of China’s circular economy and ecological modernization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(15): 1494-1501.

Payne, A., Ballantyne, D., & Christopher, M. 2005. A stakeholder approach to relationship marketing strategy: The development and use of the ‘six markets’ model. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7/8): 855-871.

Payne, A., Frow, P., Steinhoff, L., Eggert, A. 2020. Toward a comprehensive framework of value proposition development: From strategy to implementation. Industrial Marketing Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.015

Payne, A., Frow, P., Eggert, A. 2017. The customer value proposition: evolution, development, and application in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(4): 467-489.

Payne, A. & Frow, P. 2014. Deconstructing the value proposition of an innovation exemplar. European Journal of Marketing, 48(1/2): 237-270.

Payne, A. & Frow, P. 2005. A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69(4): 167-176.

Payne, A., Storbacka, K. & Frow, P. 2008. Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 36(1): 83-96.

Pires, G., Stanton, J. & Rita, P. 2006, The internet, consumer empowerment and marketing strategies. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9/10): 936-949. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610680943

Rodriguez, R.R., Escoto, R.P., Bru, J.M. & Bas, A.O. 2008. Collaborative forecasting management: fostering creativity within the meta value chain context. Supply Chain Management, 13(5): 366-374. DOI: 10.1108/13598540810894951

Saarijärvi, H. 2012. The mechanisms of value co-creation. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20(5): 381-391.

Schermann, M., Hemsen, H., Buchmüller, C., Bitter, T., Krcmar, H., Markl, V. & Hoeren, T. 2014. Big data. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(5): 261-266.

Schiele, H., Veldman, J. and Hüttinger, L., 2011. Supplier innovativeness and supplier pricing: The role of preferred customer status. International Journal of Innovation Management, 15(01): 1-27.

Schiele, H., Calvi, R. and Gibbert, M., 2012. Customer attractiveness, supplier satisfaction and preferred customer status: Introduction, definitions and an overarching framework. Industrial marketing management, 41(8): 1178-1185.

Schmidt, J. and Keil, T., 2013. What makes a resource valuable? Identifying the drivers of firm-idiosyncratic resource value. Academy of Management Review, 38(2): 206-228.

Skålén, P., Gummerus, J., von Koskull, C., Magnusson, P. 2015. Exploring value propositions and service innovation: A service-dominant logic study. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(2): 137-158.

Spinuzzi, C., Altounian, D., Pogue, G., Cochran, R., and Zhu, L. 2018. Articulating Problems and Markets: A Translation Analysis of Entrepreneurs’ Emergent Value Propositions. Written Communication, 35(4): 379-410.

Steinle, C. and Schiele, H., 2008. Limits to global sourcing? Strategic consequences of dependency on international suppliers: Cluster theory, resource-based view and case studies. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 14(1): 3-14.

Tantalo, C. & Priem, R.L. 2016. Value creation through stakeholder synergy. Strategic Management Journal, 37(2): 314-329.

Truong, Y., Simmons, G., Palmer, M. 2012. Reciprocal value propositions in practice: Constraints in digital markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(1): 197-206.

Ulaga, W., 2003. Capturing value creation in business relationships: A customer perspective. Industrial marketing management, 32(8): 677-693.

Vargo, S. 2020. From promise to perspective: Reconsidering value propositions from a service-dominant logic orientation. Industrial Marketing Management: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.10.013

Walker, J. 2008. Customer Value: Designing the Value Proposition. [Online] Available at: http://www.mycustomer.com/cgi-bin/item.cgi?id=133840

Walters, D. & Lancaster, G. 2000. Implementing value strategy through the value chain. Management Decision, 38(3): 160-178. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005344

Webster, F. 2002. Market-driven management: How to define, develop and deliver customer value (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Westerlund, M. 2020. Digitalization, Internationalization and Scaling of Online SMEs. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(4): 48-57. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1346

Windahl, C. & Lakemond, N. 2006. Developing integrated solutions: The importance of relationships within the network. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(7): 806-818.

Wouters, M., Anderson, J., Kirchberger, M. 2018. New-Technology Startups Seeking Pilot Customers: Crafting a Pair of VPs. California Management Review, 60(4): 101-124.

Zott, C., Amit, R. & Massa, L. 2011. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management, 37(4): 1019-1042

Keywords: new company, scaling company value, scaling-up, value proposition, value proposition alignment