AbstractStarting a company is like throwing yourself off a cliff and assembling an airplane on the way down.Reid Hoffman

This inductive study explores factors by which some new and innovative firms try yet fail to achieve born-global status. Born-global studies have a survivorship bias, with errors of omission that paint a favourable picture of how innovative and well-funded new ventures internationalise. In this paper, we counter such biases by focussing on innovative ventures that expressed intentions to become born global but failed to do so. Our findings reveal that these new ventures fail in two ways. Either they underestimate the need to tailor a portfolio of value propositions and over-extend their efforts across too many markets, a pattern called "baby born-global". Or they over-commit to one market at a time, thus limiting their capacity to develop value propositions in similar markets, a pattern called "micro multinational".

Introduction

The born-global literature sits at the crossroads between the fields of entrepreneurship and international business. Early research characterised born-global firms by having rapidly internationalised, within a few years of their inception, as well as having generated a large proportion of revenue from foreign sales (for example, Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2004; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). Since then, scholars have become sceptical of premature identification of "born-global” (Coviello, 2015), which has included a shift to studying how firms survive early internationalisation. This literature recognises the past characterisation of the internationalising process as a phase of nearly uncontrolled growth. Its emphasis on “survival” recognises the existence of failures, but still characterises internationalisation as being beyond the control of a company’s founders, and thus likely also in at least some ways unplanned, where a firm’s current set of transactions and value propositions (VPs) unintentionally gain a global appeal. Meanwhile, many founders proudly declare their intentions and plans to become global, making it difficult to distinguish between new ventures with genuine born-global intentions and plans versus those with only vague statements of intentions.

For those able to achieve legitimate born-global status, uncontrolled growth is a good problem to have. A common cause of failure is premature scaling (Marmer et al., 2011). Premature scaling is defined in the well-known Startup Genome Report as the “predominant form of inconsistency” whereby firms put the “product, team, financials and business model” dimensions of their business far ahead of or behind the “customer dimension” (Marmer et al., 2011). This speaks directly to placing an overemphasis only a sub-set of a firm’s portfolio of VPs, without a coherent and scalable business model (Baletti & Tanev, 2020; Baletti et al., 2020). The coherence of a business model prior to scaling remains an overlooked component of the classic Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur 2009), and is only achieved if the VPs and their relationship to all relevant stakeholders are aligned in a way that creates value for the startup to capture (immediately or sometime in the future if it is not immediately cash flow positive).

It is clearly appealing to scale quickly and establish a position in global value chains as soon as possible, a process recently referred to as “blitzscaling” (Hoffman & Yeh, 2018; Kuratko et al., 2020). The reality however is that scaling too early often leads to failure because the investment in scaling cannot be recuperated quickly enough. Entering international markets adds complexity to a new venture’s portfolio of VPs because each aspect of the business model is likely to require tailoring to specific new markets. We emphasise VPs here because the emergent literature on VPs distinguishes differentiated transactions that require an investment to develop and maintain an improved VP over time from standardised business transactions (Baletti & Tanev, 2020; Baletti et al., 2020). This qualitative emphasis on tailoring VPs is more holistic than the born-global literature’s quantitative emphasis on studying the number of markets and proportion of sales exported.

Overall, decisions on how and when to scale are certainly not left to chance at the whims of external factors and are ideally considered early in a company’s life. This article looks back at the very early days of firms to consider how they present themselves as being globally scalable. It likewise compares the historical business actions with their stated intentions. By focussing on not-yet-born-globals that have born-global intentions, we also aim to fill a gap in the born-global literature regarding failure to scale. This omission of failures and corresponding survivorship bias is a real concern for the international entrepreneurship field (noted as early as Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, 1993). This inductive study investigates why companies that express early global intentions to their funders have not been able to fulfil those intentions. In doing so, it enhances traditional born-global metrics, like markets and sales, with additional consideration of the effort and action required to manage the increasingly complex set of VPs.

This study begins by examining the literature on born-global firms, along with their failures. The methodology and findings section summarise the main research steps and the empirical analysis of four case studies of Australian-based firms that embarked on an internationalisation process with global intentions, yet have failed to achieve born-global status. Finally, we offer a framework and conceptual model that explains how this occurred. The conclusion provides a reflection on the value of the research findings.

Literature Review

Born-Globals

The born-global literature sits at the crossroad between the fields of entrepreneurship and international business. The term “born-global” was first coined in an article in The McKinsey Quarterly by Rennie (1993), which sought to describe manufacturing firms in Australia that began exporting 2 years after their inception, and that had acquired significant foreign sales.

Definitions in the core literature continued to sample on dependent variables, such as Knight and Cavusgil (2004) classified “born-globals” as the period from domestic establishment to initial foreign market entry, occuring in less than 3 years and with companies exporting at least 25% of their production. Similarly, Chetty and Campbell-Hunt (2004) defined them as “firms that began to internationalize within two years of their inception. In addition, 80% of their sales are in global markets”.

Meanwhile, Oviatt and McDougall’s (1994) seminal paper defined born-globals as a “business organization that, from inception, seeks to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources and the sale of outputs in multiple countries”. The latter definition highlights the importance of a firm’s intention to internationalise rather than its subsequent performance in global markets. The issue with defining a company based on its intentions is that intentions are easier to express and forge than is gaining actual market traction.

Modern born-global research further differentiates “born-globals” from “global startups”, where the latter include globally distributed teams and markets (Coviello, 2015; Tanev 2017), enabled by the operation of online offices (a trend that is accelerated today by the spread of Covid-19). While global startups are interesting, here we focus on more conventional innovative new ventures and their globalisation efforts.

To understand how born-global firms can rapidly internationalise, scholars have investigated what factors are uniquely distinctive to these types of organisations (Knight & Cavusgil, 1996, 2004). Among others, factors such as “global technological competence, unique product development, quality focus, and leveraging foreign distributor competences” (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004) have been studied many times over. More recently, Coviello (2015) provided a thorough overview of the born-global literature, pointing out that, if one wants to study a born-global firm, then that firm should have been founded with the intent to serve global markets, that is, globalization should have been part of its founding intent.

In this paper, we focus on how founders with global intentions use their limited resources to develop VPs that are aligned with the global markets they are trying to access. Our emphasis on VPs recognises that goods and services aren’t simply exported as is, but that the VP they embody needs to be tailored, which often requires adapting other parts of the business model (finding local overseas suppliers, distributors, partners, investors, professional service providers, employers, etc.).

Failure

“Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan” (proverb, source uncertain).

Failure can happen at many levels. Failing to learn from individual mistakes can lead to more systematic failure and ultimately business failure. At the level of business failure, many studies have concluded financial shortfalls as being the cause of failure (Lussier, 1995; Balcaen & Ooghe, 2006; Pardo & Alfonso, 2017). Questions remain about causes of the financial shortfalls and their combination. Franco and Haase (2010) investigated how multiple internal and external factors combine towards business failure, stressing the effect of a combination of factors rather than attributing failure to one exclusive factor. In many cases, they found that failure factors arose in the development and growth stage, as opposed to during the creation stage. So, while new ventures may have found a means to survive in the short term, they may still fail at scaling or growing.

This creates a series of challenges for new ventures. First, to develop VPs and a business model that scales for a given market. If the VPs for a company are only efficient when fulfilled at a smaller scale, then scaling prematurely will kill the business. Secondly, even if fulfilling the VP is more efficient at a larger scale, entrepreneurs are at risk of over-investing in attempting to build for scale prior to realising the actual benefits of scaling. This is known as “premature scaling”, where founders “overspend early on customer acquisition, hire too many employees, designate executive management too early, and focus too much on engineering at the expense of customer development” (Marmer et al., 2011). Thirdly, compounding the above risks, entrepreneurs sometimes seek internationalisation as a way to mitigate having an unsustainably small domestic market or in pursuit of growth. Internationalisation, however, requires adapting a business model to each new context (Onetti et al., 2012), and thus VPs for each stakeholder involved in the business model, including suppliers, distributors, recruiters, investors, employees, partners and more, not just customers. Scaling internationally, thus introduces several opportunities to develop appropriate VPs. Some of these stakeholder interactions may be transactional and do not involve jointly developing value propositions. At best, the lack of VPs can be a missed opportunity to create more value and may leave “money on the table”. At worst, the relationships among stakeholders interact in a negative way. For example, one bad transactional relationship can hinder the available resources required to maintain other relationships. Challenges with one stakeholder type can have ripple effects across other VPs and stakeholders (Bliemel et al., 2014).

There are clearly several reasons and attributions for failure to internationalise. The many reasons for failure are nonetheless consistent with the premise that growth and success internationally are achieved by aligning the VPs of multiple stakeholders, including suppliers, distributors, employees, investors, service providers, and many more. To make a portfolio of VPs and stakeholders more manageable to explore, this study focusses on the very early days of new ventures, when founders are seeking government commercialisation funding. During this period, when there are few other stakeholders, company scalability can be primarily based on the company’s particular scientific or technological intellectual property, while commitments to scale are still tentative.

Conceptual Gaps and Research Direction

The born-global literature displays a weakness in the lack of studies that identify why firms with pre-born-global characteristics fail to eventually attain born-global status as defined in the born-global literature. Coviello (2015) clarified that we “must distinguish between: (1) firms that are truly ‘born’ with the intent to serve multiple foreign markets quickly, and (2) firms that simply happen to export early”. This effectively returns the conversation to a broader definition of international new ventures based on Oviatt and McDougall (1994), combined with an exploration of inhibitors to scaling (that is, sources of failure to internationalise). This weakness has been perpetuated in the born-global and international entrepreneurship literature for over two decades. The recent bibliometric analysis of research from 1994-2016 does not even once mention “failure” (Dzikowski, 2018). This gap between the reality for companies attempting to internationalise and what is written on the born-global topic by researchers in the field is alarming. It displays problems with survivorship bias (Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, 1993), which can lead to overly optimistic beliefs and incomplete theoretical models due to ignoring failure cases.

Andersson and Wictor (2003) argued that although much of the born-global literature focuses on successes, “all entrepreneurs with a global vision do not succeed with their intentions”. They therfore highlighted the need for more studies to focus on the nexus of intentions to scale along with born-global failure. This was later echoed by Ţurcan et al. (2010) who argue that a “challenge for the researchers is to minimise coverage bias by studying not only successful events but also events that deviate from what can be considered expected”.

In the present study, we compare companies that started with similar pre-born-global conditions and intentions, but which did not lead to born-global outcomes. This study's broader research question is thus: Why do firms with early global intentions fail to achieve born-global status? More specifically, and rephrased in terms of a company’s portfolio of VPs that requires investment to develop, align, maintain, and improve multiple VPs over time, our research question becomes: For firms with born global intentions, what are the pathways by which their actions become misaligned from the proper development of their VPs? To address this research question, we first explore each company’s intentions to globalise early, followed by their choice of market entry mode. We interpret these intentions and choices through the lens of international entrepreneurial orientation before presenting our final framework.

Methodology

The context of this research is investigating Australian SMEs that have failed to achieve born-global status. For the last decade, the Australian economy has been consistently consisted of only 0.2% large employers, with between 6% – 6.4% of employers having 20-199 employees SMEs (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2012, 2020). This extremely skewed distribution reflects an economy that is dominated by oligopolies, surrounded by a plethora of small niche players. In oligopolies, the incumbent’s position is rarely based on innovativeness. Meanwhile, for the sake of national job growth, innovation and wealth creation, democratically elected governments have a responsibility to cultivate more innovative and competitive mid-size SMEs by investing in a subset of scalable new ventures.

The study uses an inductive approach to theory building through a multiple-case approach (Eisenhardt, 1989). The first phase of the study involved disseminating an online questionnaire to 107 firms that were recipients of a Commercialisation Australia grant. The Commercialisation Australia program was a merit-based assistance program that ran from 2010 to 2014, where the Australian Federal Government offered “funding and resources to accelerate the business building process for Australian businesses, entrepreneurs, researchers and inventors looking to commercialise innovative intellectual property” (AusIndustry, 2010). Being a recipient of this grant constitutes a public signal of the company’s growth intentions and potential value to stakeholders. VPs by applicants must implicitly create economic growth (including jobs, taxes, and exports), showcase Australian innovation, and inspire others to become high-growth SMEs.

Of the 107 firms that were invited to take part in the survey, 14 completed responses. From these 14 participants, 4 firms were selected for a Phase II case study analysis (see Table 1). To be included as a case study of a born-global failure, firms had to confirm that they had intentions to internationalise within 3 years of inception. This draws on the central tenet of Oviatt and McDougall’s (1994) seminal definition of an international new venture, where from inception, a firm must seek to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources and sale of outputs in multiple countries. In addition to this initial intention, firms had to meet one or more of the following criteria to be included in Phase II of the study:

-

It took longer than 3 years from inception for the company to enter its first international market (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004)

-

The company derives less than 25% of its total revenue from foreign sales (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004)

-

The company was active in less than ten countries outside of Australia and New Zealand (Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2004)

Semi-structured interviews were used as the main source of data collection, consistent with Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007). Interviews typically lasted from 35 minutes to 1 hour, and either took place in the firm’s office or were conducted over the phone with key decision makers in the internationalisation process. In addition to the interview data and survey, findings were triangulated using company websites, follow-up emails and other secondary data, such as press releases.

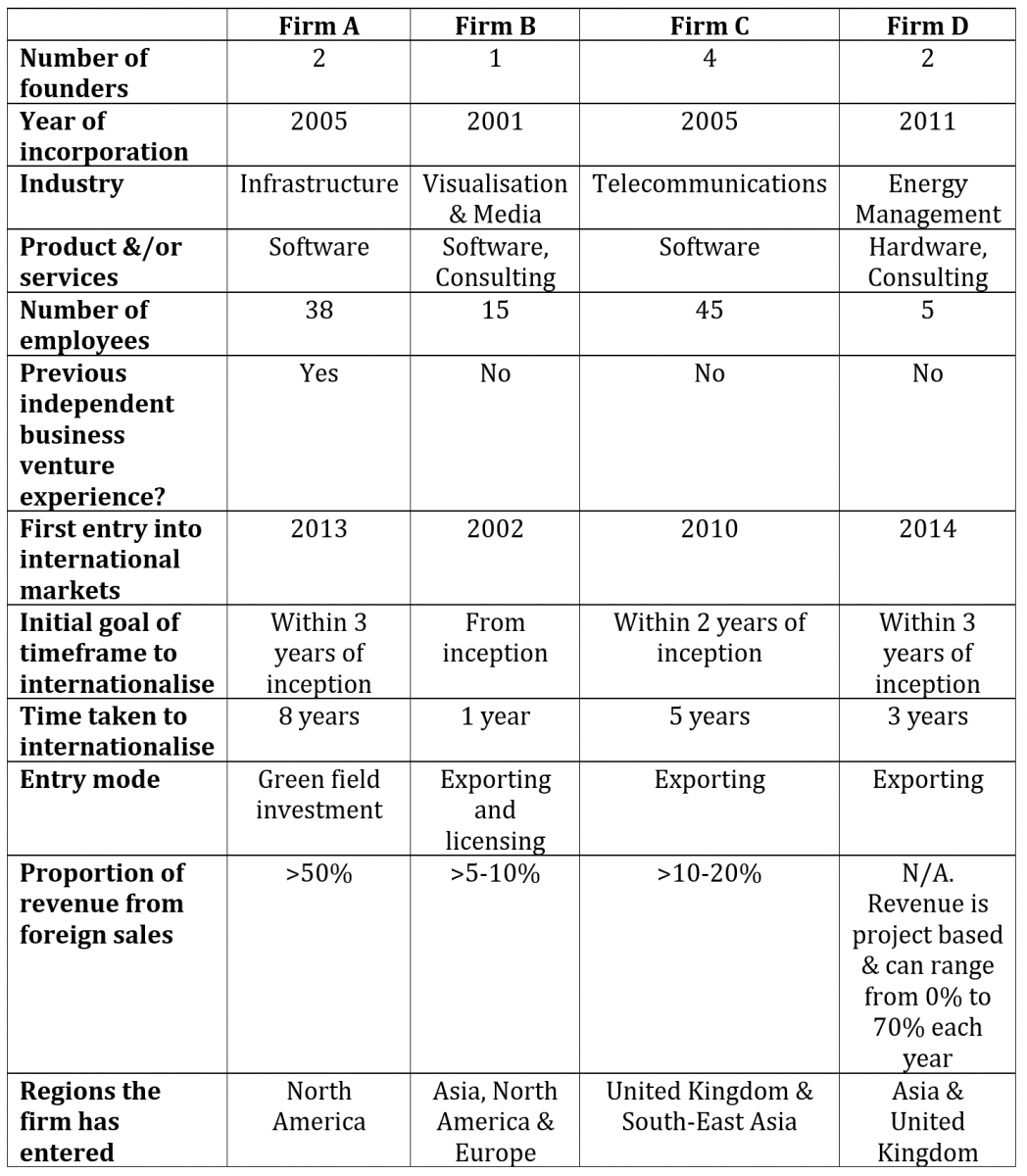

Table 1. Summary of Case Studies

We developed the propositions based on a qualitative analysis of the interviews following the general guidance by Gioia et al. (2012), and Strauss and Corbin’s (1998), complemented by theoretical insights based on the literature. Due to the low incidence of observed failures due to survivorship bias, the qualitative analysis adds empirical richness to the propositions.

Analysis and Findings

Intention to Internationalise Rapidly: broader market vs. market niche-centred internationalisation process

It is important to distinguish whether the firms had authentic intentions to internationalise rapidly and allocated significant resources towards this goal, or if their intentions to scale were perhaps more symbolic. For Firm A and Firm C, the founders’ intentions to internationalise were based on a conscious desire to build a company with scalability. The founders of Firm A had previously operated multiple companies, each with a barrier to its scalability, which led them to abandon these business models to pursue the next scalable business:

“So, this is my fourth or fifth business and every business I’ve gone ‘It’s got to be more scalable than that’. So, every time I’ve always wanted to build a really big global business”. (Founder, Firm A)

For the founders of Firm B and Firm D, the main intention to globalise rapidly was to gain access to a larger customer base. This was primarily due to the constraints of Australia’s comparably small market size, and near-agnosticism about which international market to expand into:

“The reality with Asia and China and even India is their population base… There’s certainly a big market there! Again, the size of the market in the States is much bigger than our market here.” (Founder, Firm B)

“Australia’s market is pretty small and defined and limited, and so going outside of Australia is really the only way you can expand the overall market.” (Founder, Firm D)

These findings support Bell et al. (2003), who argued that the intentions and objectives of traditional companies for internationalisation are driven by the need for survival in markets that are increasingly competitive globally, thus prompting a need to gain greater global market share. In juxtaposition to traditional firms, born-global firms usually internationalise by first seeking to gain first mover advantage and rapidly saturate a global niche market, ideally by optimally exploiting their networks and resources (analogous to effectuation theory). For three of the case studies (Firms A, B and D), the main intention to internationalise was more suited to traditional firm internationalisation than born-global niche strategies. These cases sought to – perhaps naively – gain more access to market share and generate more sales revenue without necessarily tailoring their value propositions to those markets. In contrast, born-global firms tend to focus their limited resources on purposefully developing products to exploit international niche markets. Thus, the interviews and literature confirm that a company’s intention for internationalising is an important indicator of whether it is likely to achieve born-global success, contingent on whether it tailors those intentions to a niche market or aims for broader markets. This leads to our first proposition:

Proposition 1: New ventures are more likely to fail at achieving born-global status if their main intention for internationalising is to gain access to a broader and more diverse market base. Conversely, failure at becoming born-global is less likely with a more market niche-centred internationalisation process.

Choice of Entry Mode: low vs. high commitment entry modes

All company founders stated that they had intentions to internationalise within 3 years of inception. This section evaluates choice of market entry mode. Firm A entered the US market through a green field FDI. This mode was resource intensive for Firm A’s US operations and exposed them to a higher risk of failure. Firm A derived two-thirds of its total profit from its operations in the United States, while deriving one-third of its revenue from its domestic operation. The firm perceived that the US market would be most receptive to the company’s technology, and thus allocated most of its resources for internationalising to this country. This path to internationalisation supported the findings of Agarwal and Ramaswami (1992), who found that “exporting is found to be relatively low in high potential markets indicating that high return/high risk investment modes are better modes in such markets”.

In comparison, Firm B, Firm C, and Firm D predominantly utilised a lower risk exporting or licensing model. Exporting is a low resource commitment mode of entry as a company does not have to contribute any of its equity to foreign operations, and is thus only bound by a contractual agreement at the product or service level, not the organisational level (Pan & Tse 2000). Exporting is more transactional and requires a simpler VP to distributors and their customers than establishing a joint venture or FDI. Exporting for these companies was associated with relatively low proportions of revenue from foreign sales, with Firm B deriving under ten percent and Firm C deriving between ten and twenty percent. Meanwhile, Firm D’s proportion of foreign revenue was unpredictable, ranging from sixty to seventy percent in one year to zero percent in the next.

The companies that utilised a lower resource commitment mode (Firm B, Firm C, and Firm D) also operated in a wider array of geographic markets, varying from Asian markets to European markets. In juxtaposition, Firm A, utilised a higher resource commitment entry mode, and only served domestic and New Zealand clients through its domestic operations, as well as Canadian and American clients through its US operations. Taken together, these findings lead to our second proposition:

Proposition 2: Resource constraints force firms with born-global intentions to choose between more transactional entry modes in pursuit of greater geographic scope versus higher commitment entry modes in pursuit of greater market traction in a very limited number of markets.

International Entrepreneurial Orientation

A general intention to become a born-global company differs from thoughtful consideration and actions to get there. The concept of “entrepreneurial orientation” is linked to a company’s decision-making, as well as strategic orientation (Gerschewski et al., 2015). In reference to international entrepreneurial orientation, Knight and Cavusgil (2004) define it as “the firm's overall innovativeness and proactiveness in the pursuit of international markets. It is associated with innovativeness, managerial vision, and proactive competitive posture”. One normative implication is that globalisation should not be left to happenstance and chance, but should rather be a deliberate process. To understand a company’s international entrepreneurial orientation, it is important to assess its innovativeness, and the founder’s managerial vision, as well as how proactive the firm has been in seeking success in international markets.

Innovativeness

To receive government funding through a Commercialisation Australia grant, companies had to demonstrate technological innovativeness. In their grant application, they had to explicitly state the type and level of innovation, including identifying relevant technical innovation and newness to one or more markets. The company founders also highlighted the importance that innovation and R&D played in developing their respective technologies. An example of this is the amount of time and resources the founder of Firm C dedicated to the developmental phase of the company’s technology to ensure a strong market fit:

“When the company was incorporated, we spent at least two years in development before we had a service or a software that we could sell and people could use.” (Founder, Firm C)

Knight and Cavusgil (2004) found that “innovative processes that drive the development of superior, unique products appear particularly important to born-global success”. Although employing innovative processes is one part of a scalable foundation to accelerate internationalisation, it is clear from this study that utilising innovative processes is an insufficient condition along for born-global success. All the firms included in this study could demonstrate the innovative nature of their products. However, none of these firms was able to translate it into becoming a born-global success.

Managerial Vision

All company founders had intentions to internationalise from early in the company’s timeline. However, actual company actions conflicted with these stated intentions. All firms initially focused their attention on the domestic market due to the perceived risk of internationalising without a strong domestic market base. The founder of Firm A even mentioned that one of the drivers to eventually focus the firm’s attention abroad was due to limited traction in the domestic market. For two out of the four firms (Firms B and D), the few export sales that did happen were largely opportunistic and client-driven as opposed to strategic efforts of market expansion on the company’s behalf.

The companies in this study lacked conviction regarding their managerial vision to globalise rapidly. Current theory proposes that managerial motivations play a key role in the success or failure of born-globals (Knight & Cavusgil, 2005; Freeman & Cavusgil, 2007). This variation in behaviour was highlighted by Rialp et al. (2005), who found that “early entrepreneurial entry into foreign markets characterise born-globals while traditional exporters’ key decision-makers generally tend to recognise opportunities in potential export markets on a more gradual basis and only after a stable market base has been achieved at home”. While the company founders involved in this study claimed to have had intentions to rapidly globalise, their subsequent behaviour was more aligned with the actions of traditional exporters who take a more gradual path to internationalisation. This suggests they lacked concreteness and conviction in their vision of how to rapidly globalise.

Proactiveness

Proactiveness, in respect to international entrepreneurial orientation, refers to the expectancy and initiatives to pursue new opportunities in international markets through actively seeking market opportunities, as opposed to simply reacting to competitors (Freeman & Cavusgil, 2007). The founder of Firm A displayed a willingness to take risks and pursue opportunities that existed because of the perceived technological superiority of the company’s offerings in the US market. After eight years of focusing predominantly on the domestic market for revenue generation, taking the initiative to present at a trade show in the United States triggered the founder’s decision to pursue this market due to the positive reception the firm’s technology received. This level of proactivity in seeking international markets only occurred after the founders had invested years to develop a scalable business model. The founder of Firm A stated that they were willing to set up physical operations in the US market because:

“I could just see the size of the market opportunity, [so] we had to move”. (Founder, Firm A)

While Firm A clearly focused on one international market (the United States), they were deliberately less proactive in pursuing further global markets.

In comparison, the other three firms were less proactive in their pursuit of international markets with all three dividing their attention between the domestic and international markets. Although these three firms (B, C, and D) were not proactive in their search for international opportunities, they were nevertheless able to react to widely differing global markets when opportunities emerged from their network.

Taken together, these observations regarding entrepreneurial orientation lead to our third proposition:

Proposition 3: New ventures are more likely to fail to achieve born-global status, regardless of their innovativeness, if they have an unspecified global managerial vision and do not proactively pursue global markets.

Discussion

Two general patterns emerge from the above combination of characteristics, both of which increase the chances of failure to achieve born-global status.

Over-committing resources

Firm A’s internationalisation into the US market was a late but strategic decision made by the co-founders to achieve growth. Although the United States is not geographically proximate to their domestic market, a low psychic distance exists between the two countries. Psychic distance refers to “the distance between the home market and a foreign market, resulting from the perception of both cultural and business differences” (Evans & Mavondo, 2002). The similarity between the US market and the Australian market decreased the perceived risk of Firm A entering this specific market. Although the decision to enter the US market was based on strategic motives, as well as cultural similarities, the company’s entry mode was still misaligned with even the Uppsala model.

The Uppsala model proposes that firms will minimise their risk through choosing low commitment entry modes (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977) prior to high commitment entry modes. Firm A’s behaviour acts opposite to this theory’s recommendation as the firm quickly pursued a high commitment mode through establishing green field FDI.

Market-seeking FDI can be appropriate “to produce products close to local markets” (Makino et al., 2002), including a clear VP for foreign customers, suppliers, distributors, partners, and investors. Market-seeking FDI is typical for multinational corporations for whom FDI is a relatively low commitment in relation to the scale of their existing operations. It is uncommon for new ventures. Firm A’s internationalisation path drew on a market-seeking intention, but without substantial domestic operations. Firm A perceived that the market opportunity in the US was too large to dismiss due to the overwhelmingly positive reception the company’s technology received there, leading to a more eclectic rationale (as per Dunning, 1993). As this firm combined the logic of the Uppsala model and Dunning’s eclectic theory of international production (1993), it can be described as a “micro multinational”. This is also consistent with Dimitratos et al.’s (2003) discussion on micro-multinationals. It offers a logic that adds depth to Proposition 2, as articulated in our fourth proposition:

Proposition 4: New ventures are more likely to fail to achieve born-global status if they over-commit resources to developing longer term VPs in only one international market.

Under committment of resources

Born-globals are characterised by their ability to rapidly enter multiple markets. Firms B, C, and D were successful in the sense that they were able to internationalise into multiple markets quite early in their lifecycle (that is, within 5 years). However, all three firms failed to achieve substantial and continuous revenue growth in their respective international markets. The low market traction and narrow range of countries occurred because of limited marketing initiatives, which would have aided in raising awareness about the companies’ product offerings, and tailoring their VPs to those markets. Although the company founders attributed their slow internationalisation to limited capital (consistent with Freeman et al., 2006), the generated foreign revenues remained insufficient to fuel further growth. The low returns were thus a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. By under-investing what was needed to tailor and maintain value propositions specific to each market, their transactional approach gained some traction, but was insufficient to fund the investment required to yield more traction. These companies can therefore be described as “baby born-globals”, as they succeeded in entering multiple global markets, but have still not achieved significant foreign sales.

By entering multiple markets with an undifferentiated value proposition, the companies also suffered from a lack of organisational learning through the process of entering one market before another. Weerawardena et al. (2007) noted the importance of market-focused learning capability in a born-global’s successful rapid internationalisation. A company’s market-focused learning capability refers to “the capacity of the firm, relative to its competitors, to acquire, disseminate, unlearn and integrate market information to create value activities” (Weerawardena et al. 2007). The companies we studied lacked the organisational slack to develop their market-focused learning capability. Due to limited attention from the founders, along with fragmentation across multiple markets, they were unable to interpret which activities they were performing well and which aspects of their operations were valuable to their customer base in each respective market. This logic adds further depth to Proposition 2, as articulated in our fifth proposition:

Proposition 5: New ventures are more likely to fail to achieve born-global status when they over-diversify, under-commit resources across too many markets, and enter each market using transactional relationships.

The failure thus appears to be largely due to the company’s inhibited ability to learn from sequential market entry experiences, as well as a lack of investment in developing longer-term VPs.

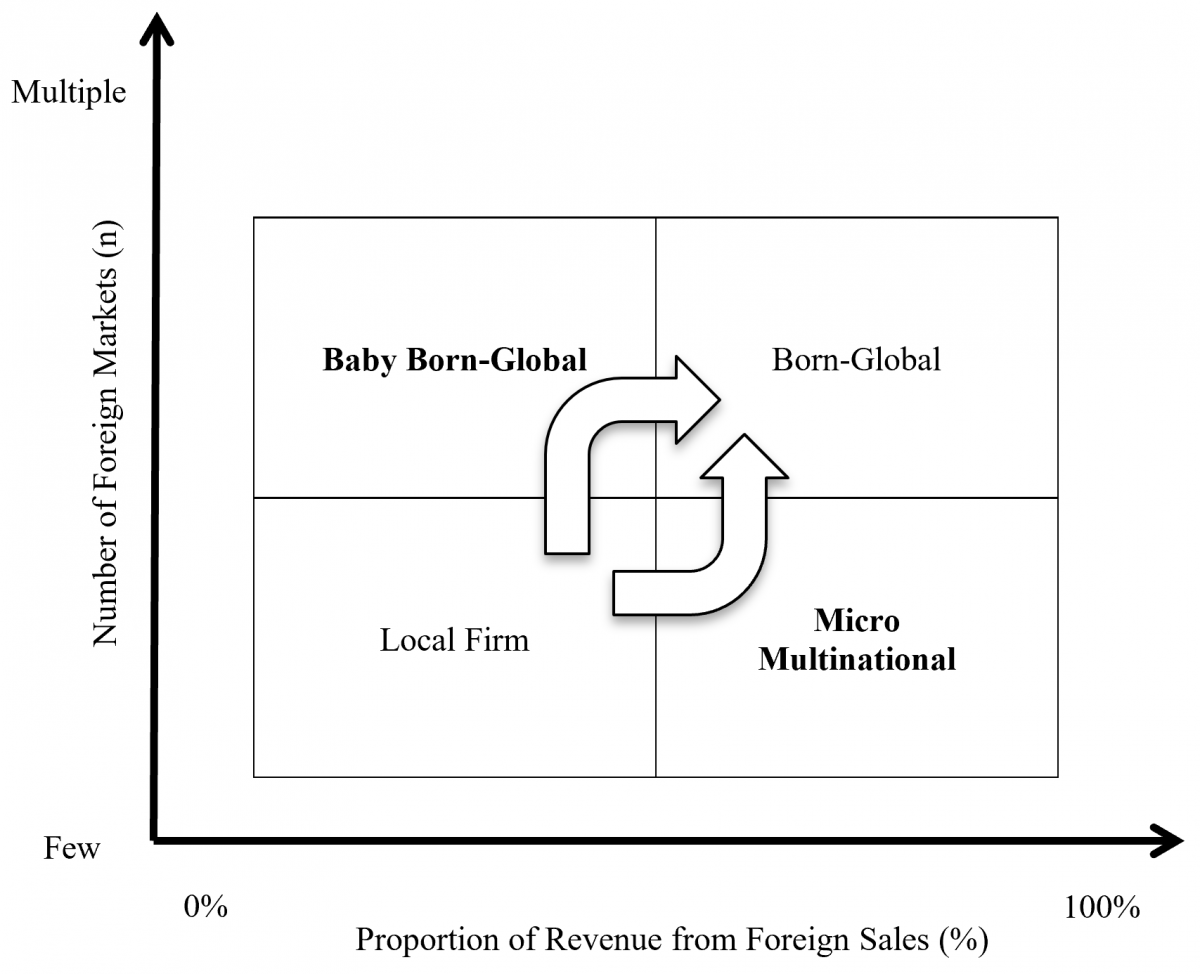

Born-Global Responsiveness Framework

These two patterns of commitment are visualised in Figure 1, to place them among the two other extreme patterns (of remaining a local firm and achieving born-global status). We developed Figure 1 by relating this study’s findings to the core literature on internationalisation models, such as born-global rapid internationalisation, the Uppsala model of low-risk internationalisation (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), and Dunning’s eclectic theory of international production by committing significant resources to each market (1993). The dimensions used to categorise firms are the criteria used to evaluate a firm’s born-global status: the proportion of revenue from foreign sales (x-axis) and scope of foreign markets entered (y-axis).

A local firm (lower left quadrant) only generates sales in its domestic market, and as a result, has no international sales. In contrast, a born-global firm (upper right quadrant) derives a significant proportion of its total revenue from foreign sales and entering multiple markets, which span a range of geographic zones.

Figure 1. Firm Paths to Scale Global Market and Revenues

In contrast, the other firms involved in this study internationalised across multiple regions by reacting opportunistically via their networks following a baby born-global model. The firms failed in each case to achieve scalability by internationalising, and instead relied heavily on assuming their domestic VPs would transfer and scale in international markets. When we adopted the definition of VPs by Bailetti, Keen, and Tanev (2020), it reinforces why especially the baby born-globals failed to achieve significant revenues. This is because they adopted a transactional approach to entering new markets without sufficiently investing towards aligning their VPs to their customers, and to other key stakeholders across each market. The context of our study thus shows an opportunity to extend the relevance of Bailetti, Keen, and Tanev’s insights (2020) by focusing on the specifics of born global firms. This extreme/unique form of new venture provides a context that highlights the need to theorise in terms of portfolios of VP.

A “baby born-global” firm (upper left quadrant) enters multiple international markets within a short period from inception. These companies share many similar qualities with born-global firms. The firms fail to achieve born-global status because their resource allocation is still predominantly allocated to the domestic market, while the firm only generates a small proportion of total foreign revenue. In contrast, a “micro multinational” (lower right quadrant) takes a significant amount of time to attain sales in foreign markets. These firms follow the general logic of the Uppsala model, which proposes that companies should first focus on their home market before selectively entering international markets (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). A slower process of increasing the number of markets is exacerbated when limited resources are fully committed to one market at a time, as with Dunning’s (1993) eclectic theory of international production through FDI. Such a high commitment entry mode limits the resources available for a company to enter other global markets, leading into failure to achieve born-global status. If companies cannot secure a significant resource base to fuel their rapid globalisation, only a few viable options exist to survive and gradually grow: either by low commitment dabbling in multiple markets (leading to baby born-globals), or slowly sequencing the company’s offerings into foreign markets, whether by gradually escalating commitments or jumping to FDI (leading to micro multinationals).

Development of a Conceptual Model

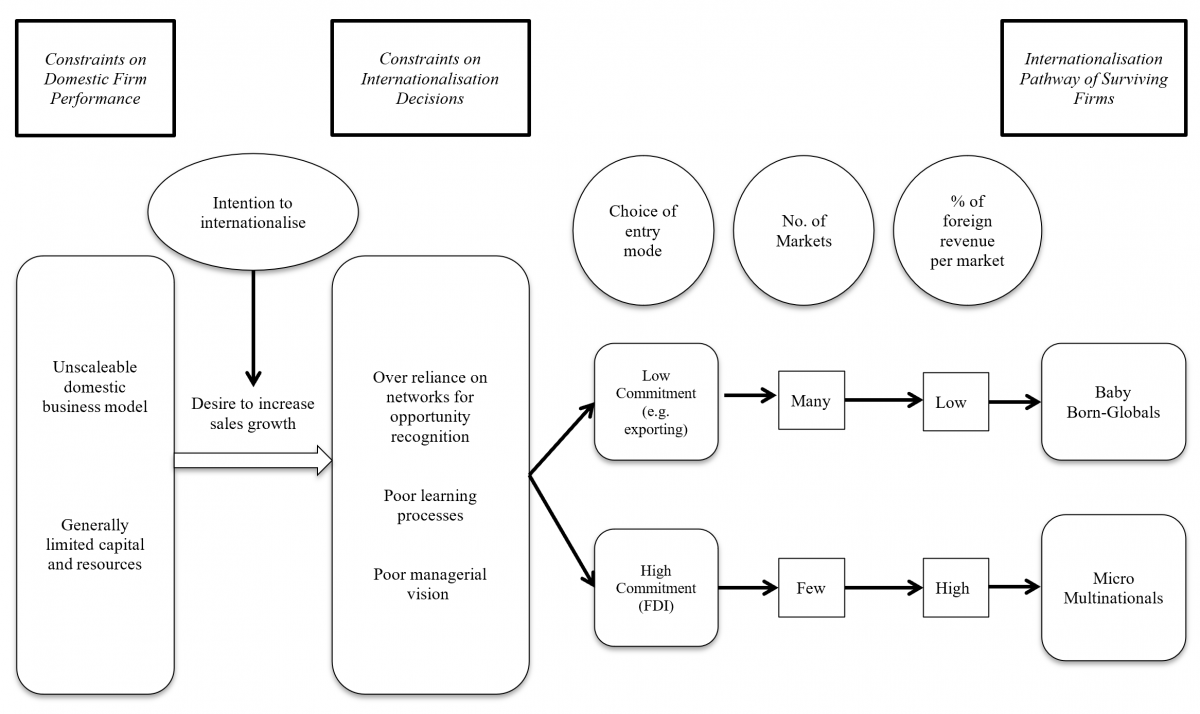

To visually conceptualise the sequence by which factors contribute to becoming a baby born-global or micro-multinational instead of a born-global, we provide Figure 2. This figure represents a conceptual model that integrates this study’s findings with the extant literature on born-globals that rapidly internationalise, and more traditional models of internationalisation. Starting with general capital and resource constraints in the domestic market on the lower left, Figure 2 lays out the role of other factors, such as the intention (or orientation) to internationalise, constraints on internationalisation decisions, entry modes, and consequences. The overall outcome of these factors leads firms to becoming a baby born-global or a micro multinational.

Figure 2: Constraints, decisions and consequences resulting in failure to achieve born-global status

Conclusion and Implications

The companies involved in this study had initial intentions to rapidly internationalise, but ultimately failed to achieve born-global status. This study developed propositions, along with a framework, and conceptual model to explain how this occurred. The main reasons included under-committing resources across multiple markets or over-committing resources to a single foreign market.

The companies we studied fitting these profiles were driven to internationalise because they perceived that entering international markets would significantly grow sales. One firm, which over-committed resources to internationalising through a micro-multinational mode, assumed that one international market had a higher knowledge and eagerness to embrace their product offering. This constrained their ability to experiment even more incrementally with other markets.

The key contribution to theory that emerged from this paper is that companies are likely to fail to achieve born-global status if they commit too many resources to a very limited number of international markets or under-commit resources across too many markets. Instead, having a more balanced portfolio of markets, VPs, and investments would likely be more fruitful. A common barrier for companies in this study was a reluctance to reallocate resources from the domestic market towards international markets as a way to avoid falling into these “not-quite born-global” ruts. In this sense, they suffered from a twofold problem: first, they tried mechanically to “copy paste” a domestic customer VP onto an international market context, and, second, they didn’t invest the resources necessary to align their customer VP to the VPs of their key cross-border stakeholders. This study thus highlighted how a firm’s VP development practices, global managerial vision, and proactiveness can be essential in either facilitating or limiting strategic global expansion. The latter has clear implications for practice relating to training or education of managers and employees in developing more proactive and thoughtful globalisation strategies.

In brief, the implications for theory proposed in this paper recognise the resource constraints of SMEs when adapting them to internationalisation theories. The challenges posed by resource constraints are compounded by the aversion of some founders to proactively explore new markets, along with an inability to align their VPs in those markets. Managers likewise need to be aware of the role that their attitudes and motivations, timing, and business networks play in the internationalisation process, as well as how they could potentially fool themselves into believing that they can export products or services with minimal investment that advances beyond a transactional model.

One limitation of this study was that it was based on a case study method of data collection, which means it can only make a theoretical generalisation and not statistical generalisation (Eisenhardt et al., 2016). However, a theoretical generalisation on this topic still holds value in helping to make existing theories more refined and incisive (Eisendhardt & Graebner, 2007). Other limitations are that the study was based in an Australian context, including predominantly software firms (3 software firms and 1 energy solutions firm). Future research could be conducted using quantitative techniques to test the model in Figure 2. In addition, this study could be applied to other geographic zones and sectors to provide a cross-cultural and cross-sectoral comparison of born-global failures. These studies would assist in contributing to reduce survivorship bias in the born-global field (Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, 1993).

References

Agarwal, S., & Ramaswami, S.N. 1992. ‘Choice Of Foreign Market Entry Mode: Impact of ownership, location and internalization factors’. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(1): 1-27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490257

Aldrich, H.E., & Wiedenmayer, G. 1993. ‘From Traits To Rates: An ecological perspective on organizational foundings’. Advances In Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, And Growth, 145-195. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/s1074-754020190000021010

Andersson, S., & Wictor, I. 2003. ‘Innovative Internationalisation In New Firms: Born Globals - the Swedish Case’. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1: 249-276. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024110806241

AusIndustry. 2012. Innovation Australia: Annual Report 2010-2011, Annual Report, Innovation Australia, Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2012. Counts Of Australian Businesses, Including Entries And Exits: June 2007 To June 2011. ABS, Canberra. 8165.0.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. Counts Of Australian Businesses, Including Entries And Exits, June 2016 To June 2020. ABS, Canberra. 8165.0.

Balcaen, S., & Ooghe, H. 2006. 35 Years Of Studies On Business Failure: An overview of the classic statistical methodologies and their related problems. British Accounting Review, 38 (1): 63-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2005.09.001

Bailetti, T., & Tanev, S. 2020. Examining The Relationship Between Value Propositions And Scaling Value For New Companies. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(2): 5-13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1324

Bailetti, T., Keen, C., & Tanev, S. 2020. Call For Papers: Aligning Multiple Stakeholder Value Propositions: The Challenge Of New Companies Committed To Scale Early And Rapidly. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(4): 1-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1365

Bell, J., McNaughton, R., Young, S., & Crick, D. 2003. Towards An Integrative Model Of Small Firm Internationalisation. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(4): 339-362. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025629424041

Chetty, S., & Campbell-Hunt, C. 2004. A Strategic Approach to Internationalization: A Traditional Versus a “Born-Global” Approach. Journal of International Marketing, 12(1): 57-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.12.1.57.25651

Coviello, N. 2015. Re-Thinking Research On Born Globals. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1): 17-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.59

Dimitratos, P., Johnson, J., Slow, J., & Young, S. 2003. Micromultinationals: New Types Of Firms For The Global Competitive Landscape. European Management Journal, 21(2): 164-174. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-2373(03)00011-2

Dunning, J.H. 1993. Multinational Enterprises And The Global Economy. Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-22973-4_4

Dzikowski, P. 2018. A Bibliometric Analysis Of Born Global Firms. Journal of Business Research, 85: 281-294. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.054

Eisenhardt, K.M. 1989. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4): 532-550. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

Eisenhardt, K.M., & Graebner, M.E. 2007. Theory Building From Cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1): 25-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

Eisenhardt, K.M., Graebner, M.E., & Sonenshein, S. 2016. Grand Challenges And Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4): 1113-1123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4004

Evans, J., & Mavondo, F.T. 2002. Psychic Distance and Organisational Performance: An Empirical Examination of International Retailing Operations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3): 515-532. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491029

Franco, M., & Haase, H. 2010. Failure Factors In Small And Medium-Sized Enterprises: Qualitative study from an attributional perspective. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4): 503-521. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0124-5

Freeman, S., & Cavusgil, S.T. 2007. Toward A Typology Of Commitment States Among Managers Of Born-Global Firms: A Study of Accelerated Internationalization. Journal of International Marketing, 15(4): 1-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.4.1

Freeman, S., Edwards, R., & Schroder, B. 2006. How Smaller Born-Global Firms Use Networks and Alliances to Overcome Constraints to Rapid Internationalization. Journal of International Marketing, 14(3): 33-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.14.3.33

Gerschewski, S., Rose, E.L., & Lindsay, V.J. 2015. Understanding The Drivers Of International Performance For Born Global Firms: An integrated perspective. Journal of World Business, 50(3): 558-575. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.09.001

Gioia, D.A., Corley, K.G., & Hamilton, A.L., 2012. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1): 15-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

Hoffman, R., & Yeh, C. 2018. Blitzscaling: The Lightning-fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Businesses. Broadway Business.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.E. 1977. The Internationalization Process of the Firm - A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490676

Knight, G.A., & Cavusgil, S.T. 1996. The Born Global Firm: A challenge to traditional internationalization theory. Advances in international marketing, 11-26.

Knight, G.A., & Cavusgil, S.T. 2004. Innovation, Organizational Capabilities, And The Born-Global Firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 124-141. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400071

Knight, G.A., & Cavusgil, S.T. 2005. A Taxonomy of Born-Global Firms’, Management International Review, 45(3): 15-35. DOI: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40836141

Kuratko, D.F., Holt, H.L., & Neubert, E. 2020. Blitzscaling: The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly. Business Horizons, 63(1): 109-119. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.10.002

Lussier, R.N. 1995. A Nonfinancial Business Success Versus Failure Prediction Model For Young Firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 33(1): 8-20.

Makino, S., Lau, C., & Yeh, R. 2002. Asset-Exploitation Versus Asset-Seeking: Implications for Location Choice of Foreign Direct Investment from Newly Industrialized Economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3): 403-421. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491024

Marmer, M., Herrmann, B.L., Dogrultan, E., Berman, R., Eesley, C., & Blank, S. 2011. Startup Genome Report Extra. Premature Scaling, 10.

Onetti, A., Zucchella, A., Jones, M.V., & McDougall-Covin, P.P. 2012. Internationalization, Innovation And Entrepreneurship: business models for new technology-based firms. Journal of Management & Governance, 16(3): 337-368. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-010-9154-1

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. 2009. Business Model Canvas, Self published.

Oviatt, B.M., & McDougall, P.P. 1994. Toward a Theory of International New ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1): 45-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490193

Pan, Y., & Tse, D.K. 2000. The Hierarchical Model of Market Entry Modes. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(4): 535-554. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490921

Pardo, C., & Alfonso, W. 2017. Applying “Attribution Theory” To Determine The Factors That Lead To The Failure Of Entrepreneurial Ventures In Colombia. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(3): 562-584. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/jsbed-10-2016-0167

Rennie, M.W. 1993. Global Competitiveness: Born Global. The McKinsey Quarterly, 45-53. DOI: 10.1509/jimk.10.3.49.19540

Rialp, A., Rialp, J., Urbano, D., & Vaillant, Y. 2005. The Born-Global Phenomenon: A comparative case study research. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 3(2): 133-171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-005-4202-7

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. 1998. Basics Of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd edn, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108324514

Tanev, S. 2017. Is There A Lean Future For Global Startups? Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5): 6-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1072

Ţurcan, R.V., Mäkelä, M.M., Sørensen, O.J., & Rönkkö, M. 2010. Mitigating Theoretical And Coverage Biases In The Design Of Theory-Building Research: An example from international entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4): 399-417. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0122-7

Weerawardena, J., Mort, G.S., Liesch, P.W., & Knight, G. 2007. Conceptualizing Accelerated Internationalization In The Born Global Firm: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of World Business, 42(3): 294-306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.04.004

Keywords: Born-global, failure, internationalisation, premature scaling, value propositions