This article investigates public opinion about smart robots, with special focus on the ethical dimension. In so doing, the study reviews relevant literature and analyzes data from the comments sections of four publically available online news articles on smart robots. Findings from the content analysis of investigated comments suggest that public opinion about smart robots remains fairly negative, and that public discussion is focused on potentially negative social and economic impacts of smart robots on society, as well as various liability issues. In particular, many comments were what can only be called “apocalyptical”, suggesting that the rise of smart robots is a threat to the very existence of human beings, and that the replacement of human labour by smart robots will lead to deepening the socio-economic gap, and concentrating power and wealth in the hands of even fewer people. Further, public discussion seems to pay little attention to the debate on whether robots should have “rights”, or on the increasing environmental effects of the growth in robotics. This study contributes to the extant literature on “roboethics”, by suggesting a dendrogram approach to illustrate themes based on a qualitative content analysis. It suggests that smart robot manufacturers should ensure better transparency and inclusion in their robotics design processes to foster public adoption of robots.

Introduction

At present, we are facing a “robotic demographic explosion”. The number of robots at work and home is rapidly increasing (Lichocki et al., 2011). Tsafestas (2018) adds a note of foresight, that not only will there be many types of robots (for example, industrial, service, social, assistive, home), but also that robots will become more and more involved in human life in the near future. In particular, “smart robots” are expected to achieve widespread diffusion in society (Torresen, 2018). As such, it is best for us to be prepared, by starting to understand the effects such robots will have on society and our personal lives, so that we may, as McLuhan (1964) noted, "think things out before we put them out”.

Using the definition by Westerlund (2020), smart robots are “autonomous artificial intelligence (AI)-driven systems that can collaborate with humans and are capable to learn from their operating environment, previous experience and human behaviour in human-machine interaction (HMI) in order to improve their performance and capabilities.” That said, it is becoming increasingly difficult to categorize smart robots by their purpose, as new smart robots are now built for multiple purposes (Javahari et al., 2019; Westerlund, 2020). For example, Samsung’s “Ballie” is used as a life companion, personal assistant, fitness assistant, robotic pet, and coordinator of a fleet of home robots in a household (Hitti, 2020). Similarly, Trifo’s “Lucy” is used as a smart robot vacuum that recognizes rooms by the type of furniture it sees, while also operating as a security system that provides day and night video surveillance (Bradford, 2020).

As smart robots are starting to come equipped with AI and various levels of functional autonomy, HMI thus becomes increasingly complex, and raises a host of ethical questions (Bogue, 2014a). Robotics applications must meet numerous legal and social requirements before they will be accepted by society (Lin et al., 2011; Alsegier, 2016). Thus, Torresen (2018) argues that designers of smart robots should ensure, 1) safety (mechanisms to control a robot’s autonomy), 2) security (preventing inappropriate use of a robot), 3) traceability (a “black box” records a robot’s behaviour), 4) identifiability (a robot’s identification number), and 5) privacy (protection of data that the robot saves). Nonetheless, although public opinion on robots may be positive, there is anxiety about robots replacing humans in the labour force (Gnambs, 2019; Tuisku et al., 2019). Other concerns include, for example, technology addiction, robotic effects on human relations, the risk of a dystopian future, the lack of control in robotics development, and in general the difficult category of ethics (Cave et al., 2019; Operto, 2019; Torresen, 2018). Opinions about killer robots and sex robots are particularly polarized (Horowitz, 2016; Javaheri et al., 2019). Hence, the current need is obvious for more systematic research on the public perception of smart robots involving ethics (Westerlund, 2020).

The objective of this article is to investigate public opinion about smart robots, giving special attention to the ethical dimension. In so doing, the study reviews the main issues in what is now called “roboethics”, involving public opinion about robots, as well as further elaborates an ethical framework for smart robots, as introduced by Westerlund (2020). The study follows this framework by using a thematic content analysis of a data set consisting of 320 publicly available readers’ comments, coming from the comments sections of four freely available online news articles about smart robots. The purpose of the content analysis was to categorize public opinion about smart robots using a framework with four different ethical perspectives. In so doing, the study reveals that the majority of comments focused on the current or coming future social and economic impacts of robots on our society, emphasize the negative consequences. The results even suggest that of four ethical perspectives, the one in particular that views “smart robots as ethical impact-makers in society” is characterized by negative perceptions, and even apocalyptical views about smart robots taking a greater role in human society.

Literature Review

In order to gain a better understanding about ethical dimensions in the context of smart robots, this study reviews previous literature on this topic. It includes a conceptual framework used for an empirical analysis in the present study. As well, the study briefly addresses the state of public opinion about smart robots.

Ethical perspectives to smart robots

The field of robotics applications is broadening in accordance with scientific and technological achievements across various research domains (Veruggio & Operto, 2006). In particular, recent advances in AI and deep learning have had a major impact on the development of smart robots (Torresen, 2018). As a result of scientific and technological progress in these fields, it is increasingly difficult for manufacturers to estimate the state of awareness and knowledge people have about smart robots (Dekoulis, 2017). Further, Müller and Bostrom (2016) argue that autonomous systems will likely progress to a kind of “superintelligence”, containing machine “intellect” that exceeds the cognitive performance of human beings in a few decades.

Veruggio and Operto (2008) take this a step further by suggesting that eventually machines may exceed humanity not only in intellectual dimensions, but also in moral dimensions, thus resulting in super-smart robots with a rational mind and unshaken morality. That said, scholars, novelists, and filmmakers have all considered the possibility that autonomous systems such as smart robots may turn out to become evil (Beltramini, 2019). In response to this danger, some people have thus suggested that the safest way might be to prevent robots from ever acquiring moral autonomy in their decision making (Iphofen & Kritikos, 2019).

There are many other ethical challenges arising along with robotics, including the future of work (rising unemployment due to robotic automation) and technology risks (loss of human skills due to technological dependence, or destructive robots) (Lin et al., 2011; Torresen, 2018). Further ethical challenges include the humanization of HMI (cognitive and affective bonds toward machines, “the Tamagotchi effect”), anthropomorphization of robots (the illusion that robots have internal states that correspond to emotions they express in words), technology addiction, the effect of robotics on the fair distribution of wealth and power, including a reduction of the socio-technological divide, and equal accessibility to care robots. Likewise important is the environmental impact of robotics technology, including e-waste, disposal of robots at the end of their lifecycle, increased pressure on energy and mining resources, and the rise in the amount of ambient radiofrequency radiation that has been blamed for certain human health problems and a decline of honeybees necessary for pollination and agriculture (Bertolini & Aiello, 2018; Borenstein & Pearson, 2013; Lin et al., 2011; Tsafestas, 2018; Veruggio & Operto, 2006; Veruggio & Operto, 2008).

Robots can in various ways potentially cause psychological and social problems, especially in vulnerable populations such as children, older persons, and medical patients (Veruggio et al., 2011). Children may form a bond with robots and perceive them as friends. This may also lure parents to overestimate the capacities of robots, resulting in over-confidence involving robots as caregivers and educators (Steinert, 2014). Thus, especially designers of companion robots or smart toy robots for children and care robots for the elderly, need to consider physical, psychosocial, and cognitive health consequences and side-effects of a robot to a person (Čaić et al., 2018).

Moreover, there are issues regarding the attribution of civil and criminal liability if a smart robot produces damages (Veruggio et al., 2011). Smart robots undoubtedly have the potential to cause damage and financial loss, human injury or loss of life, either intentionally or accidentally (Bogue, 2014b). The first recorded human death by a robot occurred in 1979, when an industrial robot's arm slammed into a Ford Motor Co.’s assembly line worker as he was gathering parts in a storage facility (Kravets, 2010). Thus, it is important to evaluate what limitations and cautions are needed for the development of smart robots, especially due to peoples’ increasing dependence on robots, which may lead to significant negative effects on human rights and society in general (Alsegier, 2016).

Westerlund (2020) reviewed previous literature on “roboethics” and, based on the work of Steinert (2014), introduced a framework to identify key ethical perspectives regarding smart robots. “Roboethics” has become an interdisciplinary field that studies the ethical implications and consequences of robotics in society (Tsafestas, 2018). The field aims to motivate moral designs, development, and use of robots for the overall benefit of humanity (Tsafestas, 2018). Thus, “roboethics” investigates social and ethical problems due to effects caused by changes in HMI. This can be defined as ethics that inspires the design, development, and employment of intelligent machines (Veruggio & Operto, 2006).

Taken in this light, Westerlund’s (2020) conceptual framework builds on two ethical dimensions, namely the “ethical agency of humans using smart robots” (robots as amoral tools vis-à-vis moral agents), and “robots as objects of moral judgment” (robots as objects of ethical behaviour vis-à-vis the ethical changes in society due to smart robots). Further, Westerlund’s (ibid.) framework introduces four ethical perspectives to smart robots: 1) smart robots as amoral and passive tools, 2) smart robots as recipients of ethical behaviour in society, 3) smart robots as moral and active agents, and 4) smart robots as ethical impact-makers in society. Even though these perspectives are non-exclusive and should be considered simultaneously, Westerlund (ibid.) suggests that the framework can be used as a conceptual tool to analyze public opinion about smart robots.

Public opinion of smart robots

Gnambs (2019) proposes that monitoring public opinion about smart robots is important because general attitudes towards smart robots shape peoples’ decisions to purchase such robots. Negative attitudes about them might therefore impede the diffusion of smart robots. According to Operto (2019), robotics is often narrated in the public consciousness with myths and legends that have little or no correspondence in reality. However, Javaheri et al. (2019) note that both news media and the general public show overall positive opinion about robots, even though the discussion focus has shifted from industrial robots to smart social and assistive robots. That said, public opinion can be polarized on issues such as increasing automation that yields both positive (workplace assistance) and negative consequences (job loss) in a society (Gnambs, 2019), including sex robots (Javaheri et al., 2019), and “killer robots” (Horowitz, 2016), which tend to raise fierce debate. Operto (2019) states that peoples’ attitudes and expectations towards robots are complex, multidimensional, and oftentimes self-contradictory. While people value the growing presence of robots, they also may show or express fears about the spread of robotics in human societies. Cave et al. (2019) found that anxiety about AI and robots is more common than excitement. Further, it is not uncommon for people to feel that they do not have control over AI’s development, advances in AI that serve to increase the power of corporations and governments, and that society’s technological development determines the progress of its social structure and cultural values. In other words, there appears to be a fairly widespread feeling against technological determinism, or at least concern about it in society today.

Method

This study draws on a content analysis of publicly available data, namely the comments sections of four online news articles about smart robots. These publicly available news articles included one from The Economist (Anonymous, 2014), two from The Guardian (Davis, 2013; Devlin, 2016), and one from The New York Times (Haberman, 2016) published in 2013-2016. Consequently, a total of 320 publicly available comments from readers of those four articles were collected from the host news media websites. The articles and their comments sections were found using Google News search, with a combination of “smart robots”, “ethics”, and “comments” as a search string. In this vein, it was expected that the search results would provide news articles that included a comments section. To be included, chosen articles needed to reflect a relatively neutral tone, and include a minimum of 20 readers’ comments to ensure higher quality data. Focusing on news articles related to smart robots from well-known news media companies resulted in four articles that met the criteria. Each of the chosen articles included between 29 and 127 comments.

The comments section is a feature of digital news websites in which the news media companies invite their audience to comment on the content (Wikipedia, 2020). Several previous studies on public perception of robots (for example, Fedock et al., 2018; Melson et al., 2009; Tuisku et al., 2019; Yu, 2020) have made use of publicly available articles, with commentaries or social media comments. Benefits in focusing on comments sections rather than social media data, include, first, that people behind the investigated comments in this study remained anonymous, as they commented on articles either behind a user-generated avatar, or without any screen name as “anonymous”. Second, the investigated news article comment sections were perceived as a feasible source of information. This is based on two features, that the articles are moderated in accordance with the host site’s legal and community standards, and that their moderators tend to block disruptive comments and comments aiming to derail the discussion and debate (Gardiner et al., 2016). Also, Calabrese and Jenard (2018) note that moving off-topic is less common in news media commentaries, in comparison with user posts on social media platforms such as Facebook, which largely do not produce news content, but rather redistribute it.

According to Yu (2020), analyzing online comments can give valuable insights into how people perceive robotics in society. Following the examples of Fedock et al. (2018), Melson et al. (2009), Tuisku et al. (2019), and Yu (2020), for this study readers’ comments were analyzed by means of thematic content analysis, which takes an organized approach to classify textual data. Fedock et al. (2018) emphasize the fact that a written informed consent (WIC) form is not required, as researchers are simply the primary instruments in subjectively interpreting words, phrases, and sentences of publicly available data.

Following the advice of Björling et al. (forthcoming), the collected data for this study were analyzed using a two-step process. First, the researcher used open coding, which aimed at identifying comments deemed relevant for the study’s focus, and then segmented them into short, meaningful quotes, as well as encapsulating their theme in single word. As a result, the data set of 320 comments was found to include 117 comments (37 percent) that were relevant for this study, and which expressed a meaningful, coherent and identifiable theme. Second, the researcher considered common themes and outliers in the data, contemplated them against the themes identified in the literature review, and then began a more focused thematic analysis of the data, according to the short quotes organized under common themes. Similar to Fedock et al. (2018), the themes that surfaced from this analysis will be discussed below using rich descriptions.

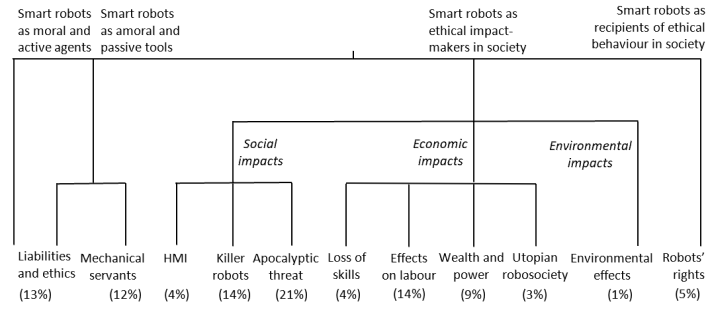

The results from the content analysis are visualized using a bar graph and a dendrogram, which is a popular method to display hierarchical clustering of similar objects into groups (Henry et al., 2015). Although such visual displays are common in quantitative research (Verdinelli & Scagnoli, 2013), some studies have suggested using them to illustrate thematic qualitative information as well (see for example, Guest & McLellan, 2003; Stokes & Urquhart, 2013). While the data does not need to be originally quantitative, the methods necessitate some kind of data quantification. For example, Melson et al. (2009) used topic counts to present relative coverage of topics in their data. Döring and Poeschl (2019) investigated representations of robots in media, and quantified a number of variables for visualising the results as a dendrogram. Creating a dendrogram requires the researcher to organize themes hierarchically according to research objectives, or in response to a perceived logical relationship among themes (Guest & McLellan, 2003). In the present study, topic occurrences were quantified according to “topic count”, and then themes were clustered applying Westerlund’s (2020) ethical framework for smart robots to organize the data.

Findings

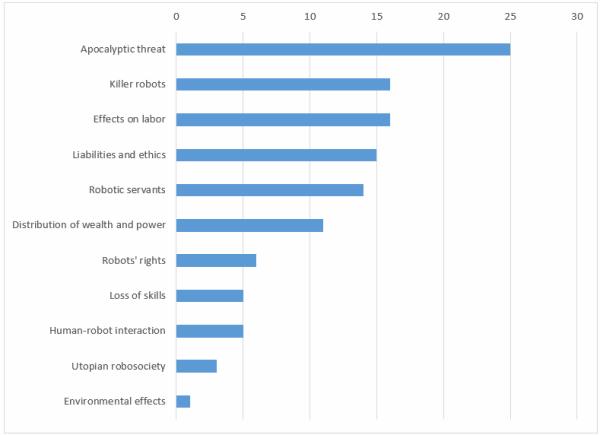

After organizing short quotes from 117 comments thematically into 11 themes, and labeling each theme in a compact characterizing manner, the number of quotes under each theme was counted. Figure 1 shows a bar graph of main themes, organized in declining order from the largest “topic count” to smallest.

Figure 1. Topic count of comments (n=117)

Apocalyptic view

The largest group of comments represented the “apocalyptic view”, where machines were seen as coming to take over, enslave, and even eventually extinguish humanity. While the reasons for this are many, the most common given was because future robots will at some point supposedly perceive humans as redundant, or even as a threat. Such apocalyptical views are seen as a consequence of robots learning and becoming increasingly intelligent, on a trajectory that some think will eventually exceed our human intellectual capacity, as well as being far superior physically. As a result, robots will emerge from servants of humans into helpmates, and then from helpmates into our overlords.

Only a few positive comments stated that the danger from robots is not a necessary outcome of their superiority, and instead that humankind will be safe and greatly benefit from robotic technology. They believed this is possible if we ensure that the developmental pathway of robots does not conflict with ours. The majority held the view that human beings as a whole would not have much chance in armed conflict against intelligent machines. Therefore, giving autonomy and rights to robots and AI systems such as Skynet – an intelligent military defense system in Terminator movies – may presage the end of the human race. Some comments added that an intellectually superior species always wins in confrontations with inferior ones; for example, gorillas are inevitably the losers in confrontations with humans beyond sheer physical strength. From this view, it is possible to conclude that, since robots do not share our same human values, they could easily become to us as we are to domestic pets, that is, as masters to another species.

Killer robots

Another major theme in the data was the notion of “killer robots”. Many commenters noted that military drones and robots are already developed and being used. The introduction of ever more destructive robotic weapons, they believed, is inevitable given the military’s role in funding and advancing robotics development. The military’s supposed interest in these fighting robots was linked to the fact that autonomous weapons are faster, safer, more effective, and more capable than only human soldiers, and that robots can carry out lethal missions without feelings of guilt or fear. Some commented that accountability for human deaths caused by an autonomous weapon always lies on those who programmed the machine as a weapon. Others pointed out that, similar to any computer technology, weaponized robots with autonomous decision-making capability are prone to “unexplained” errors and malfunctions. The lack of a robot’s capacity to reliably tell friend from foe (such as a civilian from a combatant), could lead to unintended and unavoidable deaths and injuries. Thus, an important question is raised about liability, whether or not owners and designers of autonomous fighting robots should be held accountable for killing caused by glitches in technology.

Effects of robotics on labour

Unsurprisingly, the “effects of robotics on labour” was a major theme. Some comments praised robotics as a means for developed economies to fight globalization, and the offshoring of production. Thus, robots can help local sourcing and provide new occupations and better jobs for people. However, again the majority of comments argued negatively, this time that automation is replacing both manual and non-manual workforce and stealing jobs. The argument here was that robots can work 24/7, and have no political power, which combined unquestionably makes them more profitable than even low-wage workers. The concern was that as robots come to displace certain human workers, society as a whole will face upheavals, structural unemployment, and a growing underclass of permanently unemployed. Interestingly, one comment suggested a solution to this problem: the ownership of robots should be limited to co-operatives, which could rent robots out for industrial and commercial use, as well as to individuals in need of robots. The generated revenue stream would then be used to compensate for lost human worker income resulting from the increased automation and job losses due to robots. In short, not all comments involving robotics and the future of work were full of doom and gloom.

Liabilities and ethics

Also, concerns regarding “liabilities and ethics” surfaced in the data. The analyzed comments addressed whether private individuals should be allowed to own a robot at all, and if the owner and/or the vendor of the robot could or should be sued in the event of an accident or injury. Comments also mentioned that everyone would likely try to blame someone else in such a situation. Especially the lack of transparency makes it impossible to know why designers and manufacturers make the decisions they do, and whether or not mistakes by their robots are due to a design fault or something else. That said, the majority of comments focused on the ethics guiding a robot’s decision-making process, meaning to say, what “ethics” a robot is itself coded to have. Some comments argued that robots will ultimately demonstrate the same ethics as humans, while others suggested that ethics are always subjective, and that there may be no absolutely applicable ethics. The question thus remains: whose values and ethics should be implied? Another issue was expressed that if a self-learning system emerges and evolves gradually, this would seem necessarily to lead to both unavoidable mistakes and unpredictable consequences. Such a conclusion was reached especially because robots lack essential human qualities such as kindness, compassion, empathy, love, and spirituality, which affect human values and ethics.

Robotic servants

Comments representing the perspective of “robotic servants” were threefold. Some people argued that even intelligent robots are nothing but tools and accessories for human beings to accomplish tasks, and that they are designed to work in structured and customized environments, such as factories, and to perform specific, difficult and sometimes dangerous tasks. They do not have “a mind of their own” with goals or purpose to accomplish anything beyond what they were built for, and thus robots cannot perform truly complex and sensitive tasks, such as taking care of and feeding a baby. Other comments emphasized that robots are artificial workers like household appliances, designed to be slaves that we do not need to feel guilty about. Robots in this perspective are not considered as a threat to human beings unless they start operating outside of our commands. Hence, robots should not be thought of as having emotions or feelings, such as being able to feel happy or enjoy playing a piano. Finally, many comments under this topic argued that AI is actually not “intelligence” at all, but rather something that incomprehensively resembles our understanding of intelligence. Further, the mainstream media has falsely painted a picture of AI as a super-advanced independent thinker. The reality is, however, that smart robots do not have real thought or consciousness, and even the most reliable artificially intelligent systems do well only as long as they have masses of reliable data for analysis and calculation.

Distribution of wealth and power

Comments on the possibility of a new “distribution of wealth and power” emerging due to the introduction of smart robots were fairly uniform. As long as technological advances in robotics are made available to everyone, the future is supposed to be bright. However, commenters seemed to lack belief in such a levelling generosity, and deemed instead that only the rich are likely to benefit from robots. The rich will get richer and more powerful, and will only socialize with people of their own class status. Their wealth will be measured by the number of robots they have or “own” as tireless and obedient servants and workers. Meanwhile, the middle class and lower classes will face higher prospects of losing their jobs due to automation, and more and more people will drop into poverty, while only a few rise to the top. Robots will widen not only the socio-economical gap, but also the socio-technical divide. Rich elites will program robots for their benefit and profit, while those people who are unable to handle new robotic technology will be forced to adapt or perish. Although the new wealth created with the help of robots could be used to benefit humanity, the rich elite will instead hoard it, leading to the total triumph of capital and defeat of labour. Such was often the dystopian political version of ethics that commenters voiced in relation to smart robots.

Robots’ rights

The theme of focusing on “robots’ rights” had the most positive comments. Two comments argued that not only it is inane to develop smart robots to a point where we might have to consider giving them rights, nevertheless, it would still likely take a long time before killing an intelligent machine would be considered equal to murder. Nevertheless, the rest of the comments took the approach that a freethinking robot cannot properly be thought about as a slave. Such an advanced robot should be seen as an independent non-human life form, with rights and responsibilities according to this new “artificial species”. Further, along with seeing smart robots as equal in certain ways to human beings, commenters believed we would likewise need to afford them some benefits and protections similar to humans, in terms not yet decided by the courts of law. In addition, one comment mentioned that a thriving economy necessitates consumers with incomes, so it would be better to make robots into consumers as well, just as human beings are, by paying them for their work. This line of thinking opens up countless opportunities for anthropomorphising the future of robots with human-like rights.

Loss of skills

Comments reflecting on the “loss of skills” topic, argued that, as masters to robotic servants, human beings will become lazy, thereby losing the skills of how to cook, clean, drive, and care for our children, the sick, and elderly. Such laziness, based on a naïve trust in technology, leads to a loss of basic skills, where people develop the habit of expecting to be served by smart robots that wander around our houses. This would lead to an ever-increasing technology dependency, with self-evident dangers, because eventually “the lights will go off”. In addition, the fact that smart robotic servants and companions will be programmed to make important decisions alongside of, or on behalf of their lazy masters, was seen as risky. Responsibility and blame can become unclear in problem situations, when the decision may actually have been made by a network of intelligent communication that the connected robot was part of, rather than by a robot itself. Moreover, one of the comments argued that having smart robots take over some tasks will not only lead to a human loss of skills, but also to a loss of pleasure. Many people, for example, would still enjoy driving a car in addition to just riding in an autonomous driverless vehicle.

Human-robot interaction

Issues in “human-robot interaction” have for many years in science fiction, and for fewer in industrial and professional practises, included the question of smart robots replacing human relationships, particularly in regard to raising children or taking care of the elderly. The comments emphasized the potential psychological consequences of replacing parenting with robots, and regarding the elderly potentially being confused into believing that a patient care robot actually cares about their feelings. On the other hand, one comment argued that robot companions could provide a great solution to depression from loneliness. At issue here, however, is that robots lack many human qualities, and indeed humans have to adapt their behaviour to make human-machine interaction useful. As a result, while robots are designed and manufactured to behave in some ways like humans, instead humans are nowadays also behaving more and more like machines. Another issue surfacing in comments was potentially inappropriate behaviour by autonomous robots in HMI, including unethical action, such as making racist, sexist, or homophobic remarks. That said, the comments also questioned how a robot can be sexist or racist, unless it was programmed that way. In such a case, how would one punish a robot for such behaviour?

Utopian robosociety and Environmental effects

Finally, a couple of comments addressed the birth of a “utopian robosociety”, which would mean a shift to some kind of post-capitalism scenario. These comments were largely political by nature, yet highly positive, arguing that, in the long run, technology typically improves the social and working lives of human beings. However, a concern was also raised that if labour at some point starts to rapidly disappear due to robotics, we would then need to think about how to better distribute the wealth, along with what people would do with their newly freed time. In a utopian robosociety, every human person would in principle have a fairly similar living standard, which is because essential goods such as food would be made and provided to us by robots. This means that the government would need to build automated farms running on solar or nuclear energy, which produce food for everyone. Nevertheless, cheap and ubiquitous robotics technology, with constant new models and improvements looks to become a huge future challenge, in terms of clean disposal, and recycling of robotics materials. These issues were addressed in a comment focusing on the “environmental effects” of robots.

Conceptual clustering of themes

Based on the above discussion, we grouped the themes under four ethical perspectives for smart robots. We adopted a dendrogram approach, which is a popular visual display for illustrating hierarchically clustered information. Hence, we clustered the themes that are conceptually close to each other into groups of themes. Further, following suggestions by Guest and McLellan (2003), themes were clustered by placing the resulted groups under four ethical perspectives, then applying a conceptual ethics framework (Westerlund, 2020). The vertical dendrogram in Figure 2 shows the 11 themes identified in comments as clustered into thematically similar groups. Consequently, these groups are placed under relevant ethical perspectives for smart robots, according to the relative size of each theme in the data.

![]()

Figure 2. A vertical dendrogram of main themes in comments

As a result of clustering, we can see that the notion of “smart robots as ethical impact-makers in society” was the most common ethical perspective in terms of the relative size of themes, representing a total of 70 percent of comments. Further, clustering revealed three different types of impact that people believe smart robots have, or are soon set to have: social, economic, and environmental impacts. Social impacts represented altogether 39 percent of the comments, in contrast with economic impacts, which represented a total of 30 percent, and environmental impacts just 1 percent. In total, ethical perspectives discussing “smart robots as recipients of ethical behaviour in society”, and as “ethical impact-makers in society” combined to represent 75 percent of comments, whereas ethical perspectives discussing robots either as moral or amoral actors only represented 25 percent. Of note, the theme “liabilities and ethics” surfaced in comments both from the perspectives of “smart robots as moral and active agents”, and “smart robots as amoral and passive tools”.

Discussion and Conclusion

The study’s objective was to investigate public opinion about smart robots, with special focus on the ethical dimension. Performing a thematic content analysis over 320 readers’ comments on four publicly available online news articles about smart robots, the study identified 117 relevant comments with 11 themes that surfaced in those comments. After clustering the themes hierarchically into a dendrogram, the study found that the vast majority (70 percent) of comments focused on present and coming future social, economic, and environmental impacts of smart robots. In general, the social impacts were seen as quite apocalyptical. Ever “smarter” robots might lead to the intended or unintended step of trying to destroy humanity. Comments also highlighted the economic impacts centered on robots taking over human jobs, and thereby deepening the socio-economic gap. On the other hand, 25 percent of comments viewed robots as servants to human beings, or addressed liability issues in case a robot malfunctions or demonstrates inappropriate action.

When clustered, the data illustrates a hierarchy of main concerns that revolve around smart robots’ social and economic impacts, as well as liability issues. This contributes a small, but important addition to the literature on “roboethics” by presenting a visual display that shows relevant ethical themes and their weighted importance, according to non-guided public discussion on smart robots.

While previous research has suggested that public opinion about robots is generally positive (Gnambs, 2019), the overall tone displayed in this investigation was remarkably negative. There were only a few themes with positive comments. The most positive themes were small, including “utopian robosociety”, which imagines a post-capitalist world using robots to provide welfare equally to everyone. In this perspective, “robots’ rights” would deem that eventually people should treat robots as equals to human beings. That said, previous research has also suggested people have anxiety about robots replacing humans in large numbers in the labour force (Gnambs, 2019), as well as concerns about technology addiction, the effects of robots on human relations, the risk of a dystopian future, the use of killer robots, the lack of overall control in robotics development, and both general and specific ethical questions (Cave et al., 2019; Horowitz, 2016; Operto, 2019; Torresen, 2018). All of these concerns were identified on display in the studied comments.

The findings thus confirm previously reported results. Adding to the current literature on smart robots is the finding that the majority of public discussion focuses on the impacts and implications of robots on society. There seems to be little interest in contemplating how humans should treat these robots, in the study, especially so-called “smart robots”. This supports the argument by Anderson et al. (2010), which called for more discussion on what robots’ rights might look like in the notion of “roboethics”. Also, a general lack of discussion on robots that adequately takes into consideration various current environmental perspectives and challenges, marks an interesting gap to be filled in the literature.

The findings also provide implications to technical and business practitioners in smart robotics. The lack of transparency in robotics design was mentioned as a specific problem under the theme of “liabilities and ethics”. This suggests that robotics manufacturers need to increase the transparency of their design processes, especially in regard to robots’ learning and decision-making algorithms, which specifically relate to what and how the robots “decide” to respond and act in specific environments and situations. In other words, this refers to what the robot is programmed to do by the designer, in contrast with what can be unexpected and potentially inappropriate outcomes of a robot’s learning and mimicking processes. Transparency from robotics entrepreneurs and manufacturers would not only help users to better understand a robot’s potentially awry behaviour, but also assist legal actors with whatever liability issues may arise involving accidents or inappropriate actions by smart robots.

Further, the findings support advice put forward in previous literature, especially by Borenstein and Pearson (2013), and Vandemeulebroucke et al. (2018), who argue that representatives from the target market of smart robots, such as elderly people and health and wellness or medical patients, should be involved in the design process as extensively as possible (a kind of “universal design” for robotics), and should have a voice in roboethics debates as well. A projection from this research is that addressing transparency issues in robotic product development may help contribute to better understanding the possibilities and limitations of the new technologies, thus leading to more familiarity, and increased adoption of smart robots as time goes on.

There are several limitations and avenues for future research in the current study. First, this public opinion measurement at a general level did not take into consideration sociological or political differences in attitudes between any types or groups of people. For example, the issue of “robots replacing humans as labour force” may be overly represented in the data, as readers who left comments were not identified. This group of commenters may, for example, consist mainly of people who do not have any experience with smart robots, so the capacity of their answers would be quite limited. Tuisku et al. (2019) found that people who had experience with robots at work had more positive attitudes about robots than those that did not. In their study, workers having experience with robots more often viewed robots as helpful tools, rather than as potential replacements for their jobs.

Thus, while analyzing publicly available qualitative data, such as comments sections in news articles can be useful, it is not intended to, nor could it ever replace targeted surveys that allow for comparisons based on demographic, sociographic, and other factors. Second, the articles chosen for this investigation may have affected the findings, which was a necessary risk in the filtering process. For example, Gardiner et al. (2016) note that articles in the “technology” section of The Guardian, such as those used in this study, tend to receive more comments from men compared to women, thus reflecting a gender gap in opinions. Further, a news article that takes a strong stance framing robots as a threat to the human labour force is likely to impose more comments with a more negative tone on that specific topic. Although the four articles on smart robots chosen for investigation were deemed largely neutral in tone, it is impossible to rule out the content and focus of the news article itself. Future research should therefore investigate a larger number of news articles and their commentaries, in order to balance potential biases through “scale effects”. Third, although it was useful to group the themes hierarchically using an ethical framework as a guideline, future research could also study themes in public discussion using tools better suited for quantifying themes in large data sets, such as topic modelling and hierarchical clustering software. Overall, the study reflected that research on public opinion regarding ethics involving robotics and smart robots is an important area which deserves more attention in the future.

References

Alsegier, R. A. 2016. Roboethics: Sharing our world with humanlike robots. IEEE Potentials, 35(1): 24–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MPOT.2014.2364491

Anderson, M., Ishiguro, H., & Fukushi, T. 2010. “Involving Interface”: An Extended Mind Theoretical Approach to Roboethics. Accountability in Research, 17(6): 316–329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2010.524082

Anonymous 2014. Rise of the robots. The Economist, March 29, 2014, Vol.410 (8880), [Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2014/03/29/rise-of-the-robots]

Beltramini, E. 2019. Evil and roboethics in management studies. AI & Society, 34: 921–929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0772-x

Bertolini, A., & Aiello, G. 2018. Robot companions: A legal and ethical analysis. The Information Society, 34(3): 130–140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1444249

Björling, E. A., Rose, E., Davidson, A., Ren, R., & Wong, D. forthcoming. International Journal of Social Robotics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00539-6

Bogue, R. 2014a. Robot ethics and law, Part one: ethics. Industrial Robot: An International Journal, 41(4): 335–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/IR-04-2014-0328

Bogue, R. 2014b. Robot ethics and law, Part two: law. Industrial Robot: An International Journal, 41(5): 398–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/IR-04-2014-0332

Borenstein, J., & Pearson, Y. 2013. Companion Robots and the Emotional Development of Children. Law, Innovation and Technology, 5(2): 172–189. http://dx.doi.org/10.5235/17579961.5.2.172

Bradford, A. 2020. Trifo’s Lucy robot vacuum won’t run over poop, doubles as a security system. Digital Trends, January 3, 2020. [Retrieved from https://www.digitaltrends.com/home/trifos-lucy-ai-robot-vacuum-wont-run-...

Čaić, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Mahr, D. 2018. Service robots: value co-creation and co-destruction in elderly care networks. Journal of Service Management, 29(2): 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2017-0179

Calabrese, L., & Jenard, J. 2018. Talking about News. A Comparison of readers’ comments on Facebook and news websites. French Journal for Media Research, 10/2018. [Retrieved from https://frenchjournalformediaresearch.com:443/lodel-1.0/main/index.php?i...

Cave, S., Coughlan, K., & Dihal, K. 2019. “Scary robots”: Examining public responses to AI. AIES 2019 - Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314232

Davis, N. 2013. Smart robots, driverless cars work – but they bring ethical issues too. The Guardian, 20 October, 2013. [Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/oct/20/artificial-intelligen...

Dekoulis, G. 2017. Introductory Chapter: Introduction to Roboethics – The Legal, Ethical and Social Impacts of Robotics. In Dekoulis, G. (ed.). Robotics: Legal, Ethical and Socioeconomic Impacts. IntechOpen. pp. 3-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71170

Devlin, H. 2016. Do no harm, don't discriminate: official guidance issued on robot ethics. The Guardian, 18 September 2016. [Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/sep/18/official-guidance-rob...

Döring, N., & Poeschl, S. 2019. Love and Sex with Robots: A Content Analysis of Media Representations. International Journal of Social Robotics, 11(4): 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00517-y

Fedock, B., Paladino, A., Bailey, L., & Moses, B. 2018. Perceptions of robotics emulation of human ethics in educational settings: a content analysis. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(2): 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-02-2018-0004

Gardiner, B., Mansfield, M., Anderson, I., Holder, J., Louter, D., & Ulmanu, M. 2016. The dark side of Guardian comments. The Guardian, 12 April 2016. [Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/12/the-dark-side-of-guar...

Gnambs, T. 2019. Attitudes towards emergent autonomous robots in Austria and Germany. Elektrotechnik & Informationstechnik, 136(7): 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00502-019-00742-3

Guest, G., & McLellan, E. 2003. Distinguishing the Trees from the Forest: Applying Cluster Analysis to Thematic Qualitative Data. Field Methods, 15(2): 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X03015002005

Haberman, C. 2016. Smart Robots Make Strides, But There’s No Need to Flee Just Yet. The New York Times, 6 March 2016. [Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/07/us/smart-robots-make-strides-but-ther...

Henry, D., Dymnicki, A. B., Mohatt,N., Allen, J., & Kelly, J. G. 2015. Clustering Methods with Qualitative Data: A Mixed Methods Approach for Prevention Research with Small Samples. Prevention Science, 16(7): 1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0561-z

Hitti, N. 2020. Ballie the rolling robot is Samsung's near-future vision of personal care. [Retrieved from https://www.dezeen.com/2020/01/08/samsung-ballie-robot-ces-2020/]

Horowitz, M. C. 2016. Public opinion and the politics of the killer robots debate. Research & Politics, 3(1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015627183

Iphofen, R., & Kritikos, M. 2019. Regulating artificial intelligence and robotics: ethics by design in a digital society. Contemporary Social Science, https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1563803

Javaheri, A., Moghadamnejad, N., Keshavarz, H., Javaheri, E., Dobbins, C., Momeni, E., & Rawassizadeh, R. 2019. Public vs Media Opinion on Robots. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.01615

Kravets, D. 2010. Jan. 25, 1979: Robot Kills Human. Wired, January 25, 2010. [Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2010/01/0125robot-kills-worker/ ]

Lichocki, P., Kahn Jr., P.H., & Billard, A. 2011. The Ethical Landscape of Robotics. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine, 18(1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2011.940275

Lin, P., Abney, K., & Bekey, G. 2011. Robot ethics: Mapping the issues for a mechanized world. Artificial Intelligence, 175(5/6): 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2010.11.026

McLuhan, M. 1964. Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man. Penguin.

Melson, G. F., Kahn, Jr. P.H., Beck, A., & Friedman, B. 2009. Robotic Pets in Human Lives: Implications for the Human–Animal Bond and for Human Relationships with Personified Technologies. Journal of Social Issues, 65(3): 545–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01613.x

Müller, V. C., & Bostrom, N. 2016. Future progress in artificial intelligence: a survey of expert opinion. In V. C. Müller (Ed.). Fundamental Issues of Artificial Intelligence. Berlin: Synthese Library, Springer, 553–571.

Operto, S. 2019. Evaluating public opinion towards robots: a mixed-method approach. Paladyn, Journal of Behavioural Robotics, 10(1): 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1515/pjbr-2019-0023

Steinert, S. 2014. The Five Robots—A Taxonomy for Roboethics. International Journal of Social Robotics, 6: 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-013-0221-z

Stokes, P., & Urquhart, C. 2013. Qualitative interpretative categorisation for efficient data analysis in a mixed methods information behaviour study. Information Research, 18(1), 555. [Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/18-1/paper555.html]

Torresen, J. 2018. A Review of Future and Ethical Perspectives of Robotics and AI. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 4:75. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2017.00075

Tsafestas, S. G. 2018. Roboethics: Fundamental Concepts and Future Prospects. Information, 9(6), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/info9060148

Tuisku, O., Pekkarinen, S., Hennala, L., & Melkas, H. 2019. “Robots do not replace a nurse with a beating heart” – The publicity around a robotic innovation in elderly care. Information Technology & People, 32(1): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-06-2018-0277

Vandemeulebroucke, T., Dierck de Casterlé, B., & Gastmans, C. 2018. The use of care robots in aged care: A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 74: 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.08.014

Verdinelli, S., & Scagnoli, N. I. 2013. Data Display in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1): 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200117

Veruggio, G., & Operto, F. 2006. Roboethics: a Bottom-up Interdisciplinary Discourse in the Field of Applied Ethics in Robotics. International Review of Information Ethics, 6: 2–8.

Veruggio, G., & Operto, F. 2008. Roboethics: Social and Ethical Implications of Robotics. In Siciliano, B. & Khatib, O. (Eds.). Springer Handbook of Robotics. Springer: Berlin. pp. 1499–1524.

Veruggio, G., Solis, J., & Van der Loos, M. 2011. Roboethics: Ethics Applied to Robotics. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 18(1): 21–22. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2010.940149

Westerlund, M. 2020. An Ethical Framework for Smart Robots. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(1): 35–44. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1312

Yu, C.-E. 2020. Humanlike robots as employees in the hotel industry: Thematic content analysis of online reviews. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(1): 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1592733

Keywords: Content analysis., Ethics, Public opinion, Roboethics, Smart robot