AbstractBut with lots of good ideas, implementation is the key.

Mitchell Reiss

27th President of Washington College

Service procurement is a business function of increasing importance and is highly suitable for integration of electronic support, but it suffers from severe research deficits. As yet, implementation prerequisites for electronic procurement of services are obscure and not quantifiable. In this research project, organization, formalization, and specialization of procurement and standardization and strategic importance of the procured services are identified as relevant implementation prerequisites. Measurement models for these prerequisites are established and proven through quantitative empirical research. As such, this article is a major step towards a more rigorous investigation of electronic procurement of services.

Introduction

Procurement is highly suitable for the integration of electronic support (Wu et al., 2003) as long as the information and communication technology (ICT) systems of the purchasing company and the potential subcontractors are compatible (Rajkumar, 2001). In reality, however, the actual implementation of ICT in the procurement process usually leaves much to be desired (Quale, 2005). Accordingly, procurement of services is a business function of increasing importance (Hallal et al., 2010). Yet, in spite of this importance, questions of electronic procurement of services suffer from severe research deficits (Bensch & Schrödl, 2011; Reuter, 2013).

This lack of scientific studies in electronic procurement of services is confronted by the research project on hand, which concentrates on the implementation prerequisites of electronic procurement of services arising from the organization's structure or the specific nature of the service. The research project is situated at an interface area between procurement, innovation, and service research, while also integrating aspects of business informatics. A clearly defined research framework and clearly operationalized dependent and independent variables are the prerequisites for empirical testing of assumptions. Suitable operationalization implies the existence of statistical measurement models. As yet, no such measurement models exist for the implementation prerequisites of electronic procurement of services.

Therefore, the main objectives of this research project are twofold. First, to identify the organizational structures within a company that are relevant for the implementation of electronic procurement of services from a theoretical perspective. And second, to establish and validate measurement models that allow testing for the connection between these organizational and service-related structures and the implementation of electronic procurement of services from a quantitative-empirical perspective. To reach these goals, the research project focuses on the users of electronic procurement applications. The focus on the application users is one of the four relevant foci within publications concerning electronic procurement of services, see Azadegan and Ashenbaum (2009). The precise research question that is answered in this article is:

Which prerequisites are important for implementing electronic procurement of services?

In the background section, possible implementation prerequisites arising from the organization's structure or the specific nature of the service are derived from theory. Then, measurement models based on reflective, multi-dimensional constructs are built, refined, and proven through quantitative empirical research. In the following section, the survey results are evaluated with explorative factor analysis and discussed in detail. Finally, the scientific importance of the findings is underlined and managerial advice is given.

Background

To truly understand how a company is functioning, intimate knowledge of organizational processes is crucial (Levitas & Chi, 2002). Access to external resources has a direct influence on strategic decision making within a company (Gilbert, 2005) – this holds true with procurement given that the resources of the purchasing company and the external resources from subcontractors and intermediaries are vital for the whole procurement business. However, cross-company resource requirements often conflict with internal needs. Hence, relational aspects are important. Reuter (2013) offers insights into electronic procurement of services from a relational resource-based perspective, which in this case depicts the integration of the relational view (Dyer & Singh, 1998) into the resource-based view (Lavie, 2004). This line of theory integration is apt because purchasing and supply management research is, at the moment, unable to provide insights into the management of subcontractors as external resources (van Weele & van Raaij, 2014).

The company-specific organizational structure directly influences the scale and scope of innovative action within a company and has a strong influence on the implementation itself and on the extent of application of electronic procurement tools (Reuter, 2013). Organizational structures influence capabilities, motivation, orientation, and attitude of employees. A firm’s sustainable competitive advantage depends on its organizational capital. Organizational capital consists of different structural dimensions. Centralization, formalization and specialization are very important in this context (Jansen et al., 2006).

Their importance leads to the first three possibly relevant implementation prerequisites, which are described in the subsections that follow.

Implementation prerequisite 1: Centralized organization of strategic procurement

Many companies organize procurement in a centralized, specific procurement department (Axelsson & Wynstra, 2002). The employees’ direct influence on strategic procurement leads to easier implementation of new ideas and enhances the innovation potential in procurement. Learning effects become apparent, especially in the implementation of new technologies and software solutions. From a financial perspective, centralization is beneficial as well. Centralized procurement improves the bargaining position of the firm. Demand bundling allows better procurement conditions in general and discounts in software procurement in particular (Brandel, 2010).

Implementation prerequisite 2: Formalization of procurement

Employees do their work in accordance with the roles ascribed to them (Hage & Aiken, 1967). Organizational learning and sustainable development both depend on tasks, rules, methods, and orders that are put into writing (Child, 1972). The more specific a certain task – such as electronic procurement of services – the easier it can be unambiguously described. Task specifity is the very basis of role description and increases the formalization potential of rules. To abide by these formalized rules is vital for the viability and operability of a company (Hage & Aiken, 1967). Unclear descriptions lead to confusion and disarray, which in turn, give rise to role ambiguity. In a formalized organizational structure, each employee knows what to do; this clarity simplifies decision making (Sine et al., 2006) and organizational learning.

Implementation prerequisite 3: Specialization of procurement

Organizations learn from the experiences their employees have made in former electronic procurement assignments. Especially in electronic procurement of services, specialization of employees is crucial for the efficiency of the procurement process as the knowledge basis expands and the number of specialists rises. A high number of procurement department employees, who are specialists in electronic procurement of services, raises the importance of electronic procurement of services within this firm (Reuter, 2013).

Constitutive characteristics of services can lead to notable differences in the implementation of electronic procurement of material and services. Procurement of services needs more information on the services to be procured than procurement of material. The consideration of service-related aspects is a major success factor in procuring services (Large & König, 2009). Therefore, the next two possibly relevant implementation prerequisites are identified, as described in the subsections that follow.

Implementation prerequisite 4: Standardization of services

The degree of standardization of services determines whether the services-to-be-procured can be adequately compared with each other. In spite of numerous examples of service standardization efforts, efficient, practically relevant approaches were not to be seen in the past and are still rare now (Reuter, 2013). If a service is standardized already, its degree of standardization can be identified. A highly standardized service can be procured electronically without further amendments. In this case, the respective service can be easily described. The risk of potential inefficiencies caused by inadequate description of services is minimal in this case (Ancarani & Capaldo, 2005).

If a service is not yet standardized, information about its standardization potential is sought after. A service with a high standardization potential can be easily described and can then be purchased electronically. To decide which service has a high standardization potential, the employees have to be very familiar with the services. Otherwise, misunderstandings are inevitable. In the worst case, such a misreading can result in the procurement of services that do not meet the quality standards of the procuring company. Or, the company who wins the bid (in case of an electronic auction) is not prepared to produce the offered services in the relevant time-frame because time-consuming adjustments become necessary (Reuter, 2013).

Implementation prerequisite 5: Strategic importance of services

The constitutive characteristics of services determine the degree of strategic importance of the services in question (Daub, 2009). The higher the strategic importance of a certain service, the lower seems the incentive to procure this self-same service externally. Concurrently, if the extent of external procurement of a service is low, the utilization of electronic procurement is even more improbable. The strategic importance of services (Aurich et al., 2010) seems to be another viable implementation prerequisite of electronic procurement of services.

Empirical Methodology

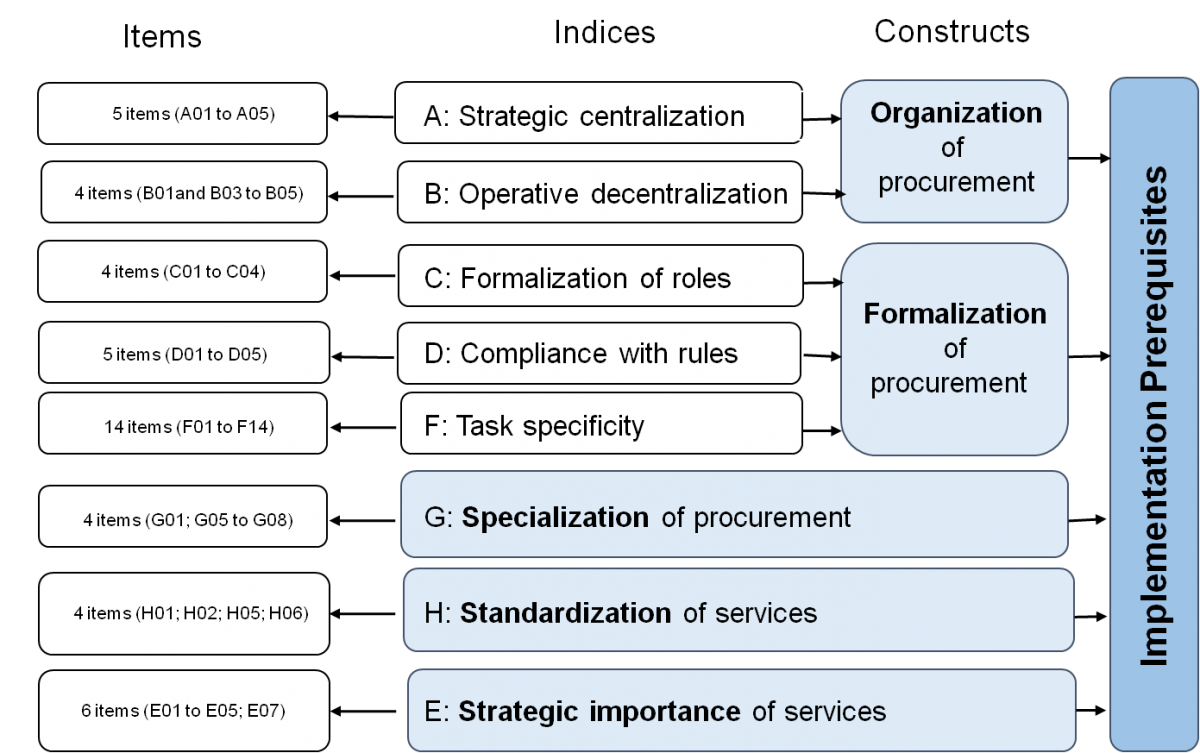

Measurement models for the different variables were created based on reflective, multi-dimensional constructs (Figure 1). These constructs condense and summarize the relevant items. Next, the measurement models depicted in Figure 1 were refined and proven through quantitative empirical research.

Figure 1. Measurement models

The construction of the measurement models requires the operationalization of the underlying constructs. Table 1 provides an overview of the constructs in the hypotheses that represent the implementation prerequisites originating from the organizational structure and the specific nature of the service. As a rule, all indices are built from several items (Curtis & Jackson, 1962). Furthermore, all underlying items are adjusted to the context of services procurement.

Table 1. Operationalization of constructs

|

Construct |

Indices / Items |

Derived By / Reliability Proven By |

|

Organization |

Strategic dimension of centralization; operative dimension of decentralization |

Dewar et al. (1980): Cronbach’s alpha 0.92 |

|

Formalization |

Formalization of roles |

Dalton et al. (1980) |

|

Compliance with rules |

Hull & Hage (1982) |

|

|

Task specificity |

Dewar et al. (1980): Cronbach’s alpha 0.76 |

|

|

Specialization |

Number of specialists |

Sine et al. (2006): highly reliable |

|

Standardization |

Describability |

Holcomb & Hitt (2007) |

|

Functional specificity |

Ancarani & Capaldo (2005) |

|

|

Strategic Importance |

Rarity |

Poppo & Zenger (1998): Cronbach’s alpha 0.82 |

|

Value |

Nothnagel (2008): reliable |

|

|

Imitability |

Nothnagel (2008) |

|

|

Substitutability |

Nothnagel (2008): reliable |

According to Deutskens, de Ruyter, and Wetzels (2006), an online survey is as reliable as any postal survey. Therefore, data was gathered online. Zikmund (2000) characterized the relevant population as a group whose participants share commonalities that are relevant for a certain statistical examination. In this case, the relevant population was the group of all facility management service providers in Germany. The exact number of participants in this group could not be determined. Therefore, a random sample was drawn from several sources. All in all, 1,048 facility management companies in Germany were identified as relevant members of the random sample.

During a survey, the researcher has no opportunity to intervene. Therefore, the design of the questionnaire is highly important and the exact meaning of items is extremely relevant in the development of measurement models. Hence, a preliminary survey was carried out in order to rule out any misunderstanding and ambiguity (Rossiter, 2002). As a result, several items were rephrased and the length of the questionnaire was reduced considerably.

The online survey itself took place in May and June 2011 using the Unipark EFS survey tool. The overall response rate was 12.5% (131 companies), which is an average, but still meaningful response rate (Röderstein, 2009) in terms of the representativity of the gathered data (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

The analysis controlled for company size (Hallal et al., 2010), company age (Aiken & Hage, 1968), and size of the procurement department (Jansen et al., 2006). None of these control variables had a significant influence on particular answers.

Evaluation and Discussion of Survey Results

The validity of reflective metrics is extremely important in correlation research. A valid metric measures what it is intended to measure (Field, 2011) and is situated within the subject area of the relevant construct (Combs et al., 2005). The items that best reflect existing correlations are identified with explorative factor analysis.

Explorative factor analysis is applicable if more than 100 questionnaires are analysed (Hair et al., 2010) and at least four items are used to build a construct (O'Leary-Kelly & Vokurka, 1998). Furthermore, the existence of correlations between items is another utilization requirement. According to Field (2011), Pearson’s r has to be at least 0.3. In the current research, all three of these basic requirements are fulfilled for the items in question. Therefore, explorative factor analysis is applicable to assess the relevance of the proposed constructs.

There are two different methods of explorative factor analysis: main axis and main component. The goal of this research project was to reduce data but to conserve most of the variables variance; hence, the main component method (Hair et al., 2010) was used. In a first step, the number of relevant components was derived with a scree test (Field, 2011). Most of the variables could be described through one single component. For those that could not, factor rotation was used (Reuter, 2013). Furthermore, the items’ factor loading was taken into account. According to Hair and colleagues (2010), factor loading has to be at least 0.5, if 120 to 149 questionnaires are considered. Therefore, nine items with factor loadings below 0.5 were eliminated from the analysis.

In a second step, factor analysis was run again with the remaining items only. Factor loadings showed that all items loaded highly on the respective factors: the results were all above 0.5. In the literature, the interpretation of extracted communalities is inconsistent. Field (2011) labelled extracted communalities of less than 0.5 as not acceptable. However, he also indicated that it is up to the researcher whether extracted communality or factor loading is used as decision criterion. Hence, most of the items exhibit high enough factor loading and high enough extracted communality to qualify as relevant. Eight items are relevant for their factor loading alone. The factor loadings and extracted communalities in question are displayed in Table 2.

Table 3 gives an overview of the second circuit of explorative factor analysis and its results. The highly significant results of the Bartlett test show that multicollinearity is evident for all tested items. Furthermore, the suitability of the random sample was tested using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criterion (Hair et al., 2010). According to Field (2011), results greater than 0.5 are acceptable. A look at the information in Table 3 (column: Suitability of the Random Sample) shows that the random sample is highly suitable to test the importance of the proposed constructs.

Furthermore, the reliability of the measurement models was tested. Cronbach’s alpha was used to illustrate the reliability of the constructs. Following Nunnally and Bernstein (2008), the results for Cronbach’s alpha are considered to be acceptable if higher than 0.6. As all results were considerably higher than this threshold; all (sub-) constructs were proven to be reliable. The results for both the multi-dimensional and the single-dimensional constructs are displayed in Table 3.

Regarding the implementation prerequisites originating from the organizational structure, the construct of organization of procurement features an average suitability of the random sample of 0.752 (KMO criterion) and explains an average of 72.496% of the existing variance. Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.755 and 0.950, which is very high. Thus, the results of explorative factor analysis show that organization of procurement is important for the implementation of electronic procurement of services.

Table 2. Extracted communalities and factor loadings

|

Construct / Sub-Construct |

Item |

Extracted Communalities |

Factor Loading |

|

A: Strategic centralization of procurement |

A01 A02 A03 A04 A05 |

0.914 0.875 0.847 0.915 0.624 |

0.956 0.935 0.920 0.957 0.790 |

|

B: Operative decentralization of procurement |

B01 B03 B04 B05 |

0.310 0.812 0.590 0.749 |

0.557 0.901 0.768 0.865 |

|

C: Formalization of roles of procurement |

C01 C02 C03 C04 |

0.785 0.825 0.804 0.266 |

0.886 0.908 0.896 0.515 |

|

D: Compliance with rules of procurement |

D01 D02 D03 D04 D05 |

0.758 0.468 0.650 0.645 0.734 |

0.871 0.684 0.807 0.803 0.857 |

|

E: Strategic importance of procured services |

E01 E02 E03 E04 E05 E07 |

0.439 0.381 0.690 0.641 0.374 0.653 |

0.663 0.617 0.831 0.801 0.612 0.808 |

|

F: Task specificity of procurement |

F01 F02 F03 F04 F05 F06 F07 F08 F09 F10 F11 F12 F13 F14 |

0.594 0.653 0.734 0.740 0.518 0.762 0.768 0.748 0.801 0.612 0.797 0.771 0.661 0.588 |

0.771 0.808 0.856 0.860 0.720 0.873 0.876 0.865 0.895 0.783 0.893 0.878 0.813 0.767 |

|

G: Specialization of procurement |

G01 G05 G06 G07 |

0.487 0.488 0.708 0.756 |

0.698 0.698 0.841 0.869 |

|

H: Standardization of procured services |

H01 H02 H05 H06 |

0.806 0.781 0.745 0.699 |

0.898 0.884 0.863 0.836 |

Table 3. Explorative factor analysis and results

|

Origin of Implementation Prerequisites |

Construct |

Sub-Construct |

Explained Variance (%) |

Suitability of the Random Sample (KMO Criterion) |

Cronbach's Alpha |

Significance (Bartlett) |

|

Organizational Structure |

Organization of procurement |

A: Strategic centralization |

83.483 |

0.829 |

0.950 |

0.000 |

|

B: Operative decentralization |

61.510 |

0.675 |

0.755 |

0.000 |

||

|

Formalization of procurement |

C: Formalization of roles |

66.981 |

0.779 |

0.819 |

0.000 |

|

|

D: Compliance with rules |

65.119 |

0.815 |

0.865 |

0.000 |

||

|

F: Task specificity |

69.612 |

0.934 |

0.966 |

0.000 |

||

|

G: Specialization of procurement |

63.631 |

0.802 |

0.847 |

0.000 |

||

|

Nature of Service |

H: Standardization of procured services |

75.768 |

0.830 |

0.893 |

0.000 |

|

|

E: Strategic importance of procured services |

52.977 |

0.775 |

0.815 |

0.000 |

||

As a construct, formalization of procurement, exhibits an average suitability of 0.843 (KMO criterion). An average of 67.237% of the existing variance can be explained with the respective construct. The results for Cronbach’s alpha range between 0.819 and 0.966. Both results are even stronger than the above-mentioned results. Hence, formalization of procurement is important in measuring the implementation prerequisites arising from the organizational structure , and so is specialization of procurement.

In what concerns the service-related implementation prerequisites, the results for standardization of procured services clearly indicate the importance of the implementation of electronic procurement of services. A small question remains regarding the strategic importance of procured services: with only 52.9% of the variance explained by the strategic importance of the procured services, it is by far the weakest of the implementation prerequisites examined.

In summary, explorative factor analysis showed that the theoretically derived measurement constructs were highly suitable for depicting the implementation prerequisites of electronic procurement of services. The partitioning into implementation prerequisites arising from the organizational structure and the nature of the service proves to be justified as well.

Conclusion and Managerial Implications

There are two different forms of prerequisites influencing electronic procurement of services. First, there are prerequisites arising from the organizational structure: organization, formalization, and specialization of service procurement. Second, there is the service-related perspective, which includes the degree of standardization and the strategic importance of the procured services.

Through this research, these five different prerequisites were transformed into constructs and measurement models. Explorative factor analysis identified the items that describe the constructs. Most of the theoretically derived items easily pass the quantitative-empirical testing. The KMO criterion shows that the items are highly suitable for measuring the random sample. Cronbach’s alpha values show that the constructs are highly reliable. Hence, quantitative-empirical testing underlines the importance of the theoretically derived prerequisites.

All in all, the implementation of electronic procurement solutions of services holds a lot of potential for future use in business-to-business procurement. The construction of reliable measurement models in the research area of electronic procurement of services is a major step towards a more rigorous investigation of this important topic.

Furthermore, rigorous investigation of this topic allows practitioners to take advantage of the scientific results. Already, practitioners can use the identified implementation prerequisites to adjust their organization's structure. The relevant managerial implications are as follows:

- Examine the organization of procurement within the company and centralize strategic procurement, leaving operative procurement decentralized.

- Formalize procurement processes in order to render them describable and more easily sought after electronically.

- Make use of or train employees specialized in electronic procurement of services. With the outlined organizational adjustments, electronic procurement of services will become much easier to handle.

The service-related implementation prerequisites can be useful when new service procurement requirements arise. For example, strategically important services should not necessarily be procured electronically, whereas highly standardized services seem a good choice for electronic procurement.

Finally, this research project has certain restrictions that should be highlighted. The measurement models were constructed with a quantitative-empirical survey within the facility management branch in Germany. This approach limits the generalizability of the research results. Therefore, the constructed measurement models should be tested again for other branches than the facility management branch and within other countries. Also, concerning the strategic importance of procured services on the usage of electronic procurement of services, the role of this implementation prerequisite should be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2014 Annual Conference of the European Association for Research on Services (RESER), which was held from September 11th to 13th in Helsinki, Finland. RESER is a network of research groups and individuals active in services research and policy formulation.

References

Aiken, M., & Hage, J. 1968. Organizational Interdependence and Intra-Organizational Structure. American Sociological Review, 33(6): 912–930.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2092683

Ancarani, A., & Capaldo, G. 2005. Supporting Decision-Making Process in Facilities Management Services Procurement: A Methodological Approach. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 11(5-6): 232–241.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2005.12.004

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. 1977. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3): 396–402.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3150783

Aurich, J. C., Mannweiler, C., & Schweitzer, E. 2010. How to Design and Offer Services Successfully. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 2(3): 136–143.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2010.03.002

Axelsson, B., & Wynstra, F. 2002. Buying Business Services. Chichester, New York: John Wiley.

Azadegan, A., & Ashenbaum, B. 2009. E-procurement in Services: The Lagging Application of Innovation. International Journal of Procurement Management, 2(1): 25–40.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2009.021728

Bensch, S., & Schrödl, H. 2011. Purchasing Product-Service Bundles in Value Networks: Exploring the Role of SCORE. ECIS Proceedings, 19(114): 1–12.

Brandel, M. 2010. IT Centralization is Back in Fashion. Computerworld. Accessed February 1, 2015:

http://networkworld.com/article/2203904/data-center/it-centralization-is...

Child, J. 1972. Organization Structure and Strategies of Control: A Replication of the Aston Study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2): 163–177.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393951

Combs, J. G., Russell Crook, T., & Shook, C. L. 2005. The Dimensionality of Organizational Performance and Its Implications for Strategic Management Research. In D. J. Ketchen & D. D. Bergh (Eds.), Research Methodology in Strategy and Management, 2: 259–286.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1479-8387%2805%2902011-4

Curtis, R. F., & Jackson, E. F. 1962. Multiple Indicators in Survey Research. American Journal of Sociology, 68(2): 195–204.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2774723

Dalton, D. R., Todor, W. D., Spendolini, M. J., Fielding, G. J., & Porter, L. W. 1980. Organization Structure and Performance: A Critical Review. Academy of Management Review, 5(1): 49–64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1980.4288881

Daub, M. 2009. Coordination of Service Offshoring Subsidiaries in Multinational Corporations. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Deutskens, E., de Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. 2006. An Assessment of Equivalence Between Online and Mail Surveys in Service Research. Journal of Service Research, 8(4): 346–355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1094670506286323

Dewar, R. D., Whetten, D. A., & Boje, D. 1980. An Examination of the Reliability and Validity of the Aiken and Hage Scales of Centralization, Formalization, and Task Routineness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1): 120–128.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2392230

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. 1998. The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Inter-Organizational Competitive Advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4): 660–679.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.1255632

Field, A. 2011. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Gilbert, C. G. 2005. Unbundling the Structure of Inertia: Resource Versus Routine Rigidity. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5): 741–763.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803920

Hage, J., & Aiken, M. 1967. Relationship of Centralization to Other Structural Properties. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1): 72–92.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2391213

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis – A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hallal, J., Xu, J., & Quaddus, M. 2010. E-Commerce Adoption in Small Enterprises: An Australian study. In J. Xu & M. Quaddus (Eds.), E-Business in the 21st Century: Realities, Challenges and Outlook: 365–393. Singapore: World Scientific.

Holcomb, T. R., & Hitt, M. A. 2007. Toward a Model of Strategic Outsourcing. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2): 464–481.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.05.003

Hull, F., & Hage, J. 1982. Organizing for Innovation: Beyond Burns and Stalker's Organic Type. Sociology, 16(4): 564–577.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038582016004006

Jansen, J. J. P., van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. 2006. Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Management Science, 52(11): 1661–1674.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576

Large, R., & König, T. 2009. Cross-Border Business Service Buying: Results of the Empirical Analysis of Influence and Success Factors. Stuttgart Working Paper Series in Logistics and Supply Management, 2(2): 1–23.

Lavie, D. 2004. The Interconnected Firm: Evolution, Strategy and Performance. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Dissertation Services.

Levitas, E., & Chi, T. 2002. Rethinking Rouse and Daellenbach's Rethinking. Isolating vs. Testing for Sources of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 23: 957–962.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.255

Nothnagel, K. 2008. Empirical Research within Resource-Based Theory: A Meta-Analysis of the Central Propositions. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. 2008. Psychometric Theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

O'Leary-Kelly, S. W., & Vokurka, R. J. 1998. The Empirical Assessment of Construct Validity. Journal of Operations Management, 16(4): 387–405.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00020-5

Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. 1998. Testing Alternative Theories of the Firm. Transaction Cost, Knowledge-Based, and Measurement Explanations for Make-or-Buy Decisions in Information Services. Strategic Management Journal, 19(9): 853–877.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199809)19:9<853::AID-SMJ977>3.0.CO;2-B

Quale, M. 2005. The (Real) Management Implications of e-Procurement. Journal of General Management, 31(1): 23–39.

Rajkumar, T. M. 2001. E-Procurement: Business and Technical Issues. Information Systems Management, 18(4): 52–60.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/1078/43198.18.4.20010901/31465.6

Röderstein, R. 2009. Erfolgsfaktoren im Supply Chain Management der DIY-Branche. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler.

Rossiter, J. R. 2002. The C-OAR-SE Procedure for Scale Development in Marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(4): 305–335.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6

Reuter, U. 2013. Elektronische Beschaffung von Dienstleistungen. Anwendungsvoraussetzungen, Dienstleistungsbeschaffungsprozess und Innovationswirkungen. Göttingen, Germany: Cuvillier.

Sine, W. D., Mitsuhashi, H., & Kirsch, D. A. 2006. Revisiting Burns and Stalker: Formal Structure and New Venture Performance in Emerging Economic Sectors. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1): 121–132.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.20785590

van Weele, A., & van Raaij, E. 2014. The Future of Purchasing and Supply Management Research: About Relevance and Rigor. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 50(1): 56–72.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12042

Wu, F., Mahajan, V., & Balasubramanian, S. 2003. An Analysis of e-Business Adoption and Its Impact on Business Performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(4): 425–447.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0092070303255379

Zikmund, W. 2000. Business Research Methods (6th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt.

Keywords: digitalization, electronic procurement, implementation, improvement, process innovation, procurement, purchasing, service management, service procurement