AbstractThere is no kind of problem that baffles one or a dozen experts that cannot be solved at once by a million minds that are given a chance simultaneously to tackle a problem.

Marshall McLuhan

Philosopher of Communication Theory

A large crowdsourcing project managed by Fiat Brazil involved more than 17,000 participants from 160 different nationalities over 15 months. Fiat promoted a dialogue with an enthusiastic community by linking car experts, professionals, and lay people, through which more than 11,000 ideas were selected and developed to create a concept car using a collaborative process. Through an in-depth case study of this crowdsourcing project, we propose a new approach – the accordion model – which uses project management to help maximize the beneficial inputs of the crowd. Whereas the stage-gate process relies on a “funnel” of articulated sequences expressing a progressive reduction from an initial stock of potential ideas and concepts, in this article, we suggest that crowdsourced projects are more akin to a process that articulates a succession of broadening and funnelling periods that represent information requests and deliveries. We use the metaphorical terminology of “the sacred and the profane” to illustrate the interaction of sophisticated and ordinary ideas between the “sacred” experts from Fiat and the “profane” lay people associated with the project. Lessons learned from the Fiat Mio case suggest how both organizations and Internet users may benefit from successful crowdsourcing projects.

Introduction

Imagine that you are a carmaker and you want to modernize your practices in product innovation. Despite all your technological progress in production, your integration of key systems, and your adoption of a state-of-the-art management style, the way you produce cars is similar to other industries: you create a first version, test it, gather feedback, produce a new version, test it again… repeating this cycle until finally you are ready to produce and sell the finished version to your customers. Essentially, this series of iterations or loops of building, testing, gathering feedback, and revising (Cooper, 2006) is still used in the majority of industries. However, what might happen if you invite your customers to co-create a car with your engineers and designers over the whole process? Would the pace still remain the same? How could you motivate and engage people in this task? Put simply, what is the best way to work with the crowd to innovate?

Starting from a single idea – to collaboratively create a car with Internet users – Fiat foresaw a favourable circumstance to achieve two goals: create a product and engage consumers. To emphasize that consumers would feel that the product belonged to them, Fiat named the project Fiat Mio, or “My Fiat” in English. The Fiat Mio project was not a competition to find the best idea or reward a winner. Right from the beginning of the project, Fiat executives felt it was improbable that lay people could come up with an idea that would surpass the quality of ideas from the experts. Nonetheless, Fiat invited consumers and their first-hand experience with cars in the hopes that they might bring novel ideas that might never have occurred to design and production experts.

In the form of "the crowd", consumers are being recognized as a new source of innovation, as evidenced by the recent crowdsourcing efforts of diverse companies and brands, such as Boeing, Eli Lilly, Du Pont, Procter & Gamble, Doritos, and Kit Kat (Huston & Sakkab, 2006; Brabham, 2008; Lafferty, 2012). Through crowdsourcing campaigns, consumers can act as co-creators by bringing their knowledge, skills, and willingness to learn and experiment while engaging in an active dialogue with the sponsor companies (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2000). In the crowdsourcing literature, very few studies, if any, have examined a large-scale project in the automobile industry or have detailed different phases of the process exploring how different levels of participation are demanded from the crowd. There is also a lack of examples on how firms adopt mechanisms to provide purposeful content to the crowd to enrich their contribution to the process and, on the other hand, how organizations may overcome cognitive fixation, meaning the tendency for experts to fixate on past examples or success, leading to less innovative ideas (Smith et al., 2013; Le Masson et al, 2006).

In this article, we examine the crowdsourcing process used by Fiat Brazil in the development of a prototype concept car. After a brief description of our methodology and the case itself, we present and analyze our results using the metaphorical terminology of “the sacred and the profane” to illustrate the role played by experts and lay people during a crowdsourcing project. Despite the fact that the product created would never be commercialized, the process itself is more relevant than its final result, as is demonstrated by the accordion model, the new approach to manage large crowdsourcing projects, which we propose based on our analysis of this case. We conclude by discussing the implications of the accordion model for Fiat Brazil and other companies engaging in crowdsourcing projects.

Our Case Study Methodology

Our methodological approach is based on an in-depth case study that is both intrinsic and instrumental. It is intrinsic because the case itself – the Fiat Mio project – deserves a deep investigation due to its originality and its pioneering characteristic in the automotive industry, particularly in South America. It is instrumental because the analysis of this particular case will allow us to advance the understanding of a broader issue: the management of large-scale projects involving a crowd of Internet users (Stake, 1998).

The data collection involved two main sources. First, we examined a large number of written materials, particularly those posted on the website of the Fiat Mio project and a book published by Fiat, but also other books, academic manuscripts, and articles in the press. Second, we performed a number of interviews with three major participants in the project. These respondents represent the two main branches of the process: the organization that created the project and the advertisement agency that conceived three phases of the project: mapping scenarios, concept ideas, and concept design. On a daily basis, the agency oversaw the traffic of data on the web-based platform and was also the link connecting Internet users with Fiat and vice versa.

The data analysis was mainly based on visual mapping techniques (Langley, 1999). We represented the different phases visually, with components and mechanisms identified in a processual-based logic.

The Fiat Mio Crowdsourcing Project

Fiat Brazil started to sow the seeds of crowdsourcing and open innovation in 2006, when the organization created a "tournament of ideas" in cyberspace. As part of their celebration of a 30-year presence in Brazil, Fiat began a discussion on its website, inviting people to freely imagine the future by posting photos, videos, comments, etc. The initial aim was to promote a marketing survey, however, as popular interest surged, it was transformed into a marketing campaign. In the same year, coincidentally, Fiat presented its first Fiat Concept Car (FCC I), which was developed by the design team of the Fiat Style Center. Two years later, the second prototype (FCC II) was presented at the 2008 edition of the Sao Paulo Auto Show. The Fiat Mio project was intended to create the third prototype, which Fiat Brazil would exhibit at the 2010 Sao Paulo Auto Show, as described in this video. The project began with the simple idea of using a crowdsourcing approach to design a new concept car, and it progressed through five additional phases, which ended with the launch of the prototype. Once enough content was generated and discussed by the crowd, the firm withdrew to treat the data internally, afterwards releasing a new briefing and a new challenge, to be collectively and continuously solved.

Phase 1: Original Idea

Seeking inspiration to build the third Fiat Concept Car (FCC III), one of the Fiat executives reported learning that automobile manufacturers tend not to respond to consumers’ real needs because some of their demands are lost during the long time lag between marketing surveys and the final launch of the product. Meanwhile, one executive from AgênciaClick Isobar, Fiat’s advertising agency in Brazil, sent copies of the book What Would Google Do? (Jarvis, 2009) to certain Fiat executives to stimulate their thinking about enhancing Fiat’s approach to innovation based on the lessons from Google.

Intrigued by how such new approaches could influence the way carmakers produce cars, this Fiat executive had an insight: to develop a collaborative co-creation process for a concept car where, through a blog on the Fiat website, people who wanted to participate could share their ideas. The idea of this project was discussed among other Fiat executives, and an opportunity for Fiat to enhance its communication approach with its clients was also identified. As a result, the advertising agency was given the task of developing a communication plan for this co-creating process addressed to stimulate the participation of Internet users worldwide. The agency would also help to guide the flow by giving the crowd references, through images and texts, regarding what was feasible. The advertising agency came up with a proposal, which divided the project into three main phases: Mapping Scenarios, Concept Ideas, and Concept Design. Based on our observations of the overall process, we identified two additional phases: Modelling and Launch.

Phase 2: Mapping Scenarios

One of the main goals of this initial stage was to generate a key question that would steer discussions on the open platform and that would later be available on the Fiat website for crowdsourcing participants. Fiat outsourced research to six automotive journalists to investigate “the car of the future and the future of cars”. Their mission was to interview specialists and map future trends and scenarios. The result of their work was an extensive report that was later summarized and presented during a workshop organized by Fiat.

Developing the open question was the final part of the Mapping Scenarios phase; when the question was posted on the Fiat Mio platform on August 2009, the crowdsourcing project was officially online. Fiat and the advertising agency released the following open question on the platform to guide customers’ discussions:

“In the future we are building, what must a car have in order for me to call it mine, without ceasing to serve other people?”

Phase 3: Concept Ideas

With the release of the Fiat Mio collaborative platform, the aim was to stimulate Internet users worldwide to participate by adding their ideas to the project, as well as to comment and vote for the ideas of others. Posts were published three times a day, and incentive reminders were sent by Twitter inviting followers to access the Fiat Mio website and collaborate. Originally, Fiat expected to receive about 500 comments, but instead they received 7,078.

Fiat's advertising agency managed the web-based platform, and a single brand content editor condensed all the information received from the crowd. In tandem with Fiat engineers and designers, this editor classified and segmented the information so that Fiat could understand the desires expressed by users. This editor acted to some extent as a bridge, connecting the professionals and lay people – “the sacred and the profane”. All of the content was filtered by the editor and, in conjunction with designers and engineers from Fiat, 21 topics of discussion were distilled (e.g., cabin space, fuel efficiency, noise cancelling, onboard biometrics) and they also served as the skeleton to be fleshed out during the next phase.

Phase 4: Concept Design

After these 21 topics had been identified, they were posted on the website for further consideration by Internet users who were participating in the project and also others who could, at any time, become part of this community. Each topic was open to individual discussion for a period of 10 days to clarify the path that designers and engineers should take. Following each question, there was explanatory text that was often accompanied by a secondary question, as the following example illustrates:

“Cabin and passengers: How many seats and doors should the Mio have? (To respond to these subjects and define the space specifications in the Mio, one must consider the following question: is the most common configuration of four to five passengers the ideal one, or would it be better to try something smaller, up to two passengers? What vehicle is missing among the wide range of options available on the market today?)”

To ensure that the suggestions would be realistic, Fiat provided 281 posts over the course of the project, including reference images and texts regarding what could be inspiring and feasible. The brand content editor guided the production of this content in collaboration with Fiat's designers and engineers. With the purpose of giving life to a prototype and in line with the suggestions submitted, the designers at Fiat started to research images, concepts, and references that would serve to produce the first sketches. They found that two concepts summarized Internet users’ aspirations: i) an organic and winding style and ii) a defined, squarish design. These orientations generated different drawings, which were grouped under two different lines: the Sense Line (i.e., organic) and the Precision Line (i.e., minimalistic). Internet users were asked to answer precise questions and then vote for their preferred option. They were also asked to indicate their preferences for proposed new technologies and design details.

Phase 5: Modelling

The dialogue did not stop when Fiat's designers began to build the prototype. Throughout the modelling phase, Fiat continued to encourage participation in the platform until the designers judged that they had enough elements to begin modelling the prototype. Fiat designers interpreted suggestions given by the crowd and presented them with options on which to vote and comment. Again, once the designers and engineers were satisfied with the features arrived at by votes and comments, they were then able to move on to another phase. The website announced:

“The unveiling of our collaborative concept car is right around the corner. Nonetheless, your participation will continue up to that moment. Now we want to show you 4 paint settings for the FCC-III to look even better when it premieres at the Auto Show. Which one do you prefer?”

Phase 6: Launch

The prototype took six months to build and it was delivered in time to be exhibited at the Sao Paulo Auto Show. Invitations were sent through Twitter, and an intensive advertising campaign encouraged participants – “the people who made it” – to see the result in person at the showroom. Fiat Cars named the crowdsourcing participants “Fiat Mio Creators”. In December 2010, hundreds of Fiat Mio Creators stood beside the mock-up at the auto show, and some of them gave testimonials about their participation, as shown in this video.

Following the launch, a Fiat executive we interviewed affirmed that the project has changed the way everyone at Fiat works. Another executive remarked that “the project sent the whole automotive industry to the “psychoanalysis couch” (Silva, 2010), while another Fiat executive we interviewed said that, in Fiat Brazil, everyone agrees that “surprising innovations come from the periphery; as they are embodied, an innovative project then moves towards more central positioning in the organization”. Fiat Mio was initially designed to be a tiny project that would involve only a handful of car aficionados around the factory, but it quickly took shape and moved from a peripheral to central concern at Fiat.

Fiat Brazil thus reinforced its connection with its customers – and hopefully gained new ones. The Fiat Mio platform continued to accept suggestions and comments by extending the period for receiving data from its consumers about their likes, preferences, habits, etc., for future use. However, both Fiat and the crowdsourcing participants were aware that the concept car might not be built as a mass-market vehicle, or might not even be commercialized. Thus, the prototype was regarded mostly as a map of consumer wishes, and some of the new features could ultimately be integrated into new cars available for purchase. As one Fiat executive said: "There are small things that don't cost much and bring great satisfaction to consumers, but haven't been given much attention. A lot of their ideas will end up going into our cars" (Wentz, 2009).

Analysis and Findings

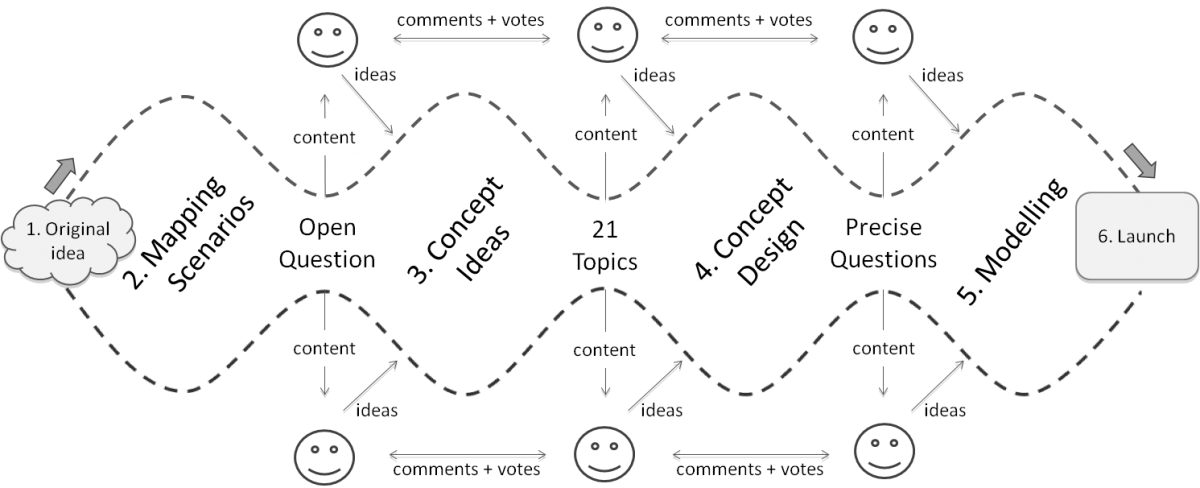

Figure 1 illustrates the six phases of the Fiat Mio project, the interaction between Fiat and Internet users, as well as the interaction between Internet users over the process. In phase 1, the original idea was generated, and the project progressed through the other phases until the completion and the launch of the prototype. The central, accordion-like shape presents broad and narrow areas that represent moments where Fiat requested and received ideas from the crowd. The shape of the figure shrinks at intervals, representing moments where Fiat digested the ideas received and then released another challenge to the crowd. For instance, at the end of the Mapping Scenarios phase, the team came up with an open question, leading to the Concept Ideas phase.

The dashed lines bypassing the shape represent the permeable boundaries separating the organization from its market environment. The illustrated faces represent crowdsourcing participants that received content from the firm – videos, references, and inspirational posts – which helped them to provide more constructive ideas to the process and to comment and vote on the ideas of others.

Figure 1. The accordion model showing the phases of the Fiat Mio crowdsourcing project

While analyzing the phases of the Fiat Mio project, we identified that this succession of broad and narrow areas, or opening and closing periods, inspired us to give it the label of the "the accordion model". The funnelling process is non-linear: an initial idea or briefing is released to the crowd, and the crowd responds to this challenge, leading to an expanding phase of idea generation. That process may reveal new trends or directions, which narrows towards another briefing or challenge to be tackled again by the crowd, and so forth. In short, when triggered by provoking questions and inspiring content, the crowd provides ideas to the process. The organization thus analyses the ideas provided by the crowd. After one or more iteration, if the organization judges that there is enough content, the project can move to another phase. Otherwise, another idea-generation phase may be triggered to generate more content. This opening-and-closing, or "accordion", process progresses until the production of the prototype.

The accordion model differs from the classic stage-gate model (Cooper, 1990) and the open innovation process (Chesbrough, 2003) where, as time progresses, both praxis progressively converges until the product is achieved. Whereas the stage-gate process relies on a linear and convergent “funnel” of articulated sequences expressing a progressive reduction from an initial stock of potential ideas and concepts, the accordion model relies on alternating periods of broadening and funnelling, where ideas are collectively generated, commented on, and selected. The difference between this linear funnelling of the stage-gate model versus the non-linear funnelling of the accordion model relies on the idea-generation mindset: in the stage-gate model, ideas are progressively eliminated, but in the accordion model, ideas are constantly and collectively multiplied. As a result, by observing the Fiat Mio project, we have identified some key characteristics that distinguish the accordion model from the classical stage-gate process: (1) the management of a lively community of users that enables (2) a rich dialogue between the “sacred” high qualified personnel of Fiat and the “profane” crowdsourcing participants who may ultimately be potential consumers.

1. Managing a lively community of users

Regarding the inspirational posts provided by Fiat, by supplying the crowd with references and purposeful content, Fiat’s advertising agency was attempting to both foment participation and improve the knowledge of crowdsourcing participants, which would be useful to enrich the discussion and receive more realistic ideas. Consequently, the crowd was prompted to provide better solutions related to the problem briefed by Fiat. Plus, we observed that, by doing this, Fiat filled the three key conditions that allow the emergence of groups (Sartre, 1985) or self-selected virtual communities: i) the interdependence between members, or web users, because participants were stimulated to see, comment, and vote the ideas of the others; ii) the awareness of a common goal, the Fiat Mio; and iii) the organization of crowd interaction, which Fiat guided and nurtured in cyberspace. This social interaction also met the needs of Internet users searching for networking and eventual recognition of the value of their ideas. For organizations, the act of attracting, gathering, and stimulating communities of users, lay people, consumers, and eventually some experts from the crowd through a well-managed social interaction plan could be a successful tool for marketing and customer relationship management in the long run. Ultimately, we could consider that a successful crowdsourcing project would help to identify emerging groups of individuals from the collective by engaging them into a common goal, thereby bringing both experts and non-experts together.

2. Promoting a rich dialogue between the “sacred and profane”

This interaction between “the sacred” (Fiat designers and engineers) and “the profane” (crowdsourcing participants, lay people) embodied by the Fiat Mio was constructive for many reasons. First, the investment made in providing relevant content provided benefits because it helped to improve customers’ subjectivity and to reduce cognitive fixation, or “something that blocks or impedes the successful completion of various types of cognitive operations, such as those involved in remembering, solving problems and generating creative ideas” (Smith, 2003), that expert professionals are likely to undergo (Bayus, 2013). On the other hand, the individuals from the crowd benefited, because the eventuality of “working outside” the company helped some of them to develop a network and obtain some visibility according to the success of their ideas.

Second, regarding information exchange, by providing clear, relevant, and purposeful content to crowdsourcing participants, the organization optimized the quality of the ideas provided by the crowd in terms of feasibility and innovativeness, therefore, making the ideas useful for experts. By both posting a challenge and providing inspiring content related to the solution desired, the crowd provided, with their ideas, free association of uses and applications that appeared innovative and original for the “sacred” experts’ eyes.

And, finally, crowdsourcing also destabilized and brought a slight amount of cognitive dissonance into Fiat Brazil, which, according to one executive interviewed, “it was also important for us to understand changings and trends in the market environment”. This interaction between “the sacred and the profane” also favoured the dialogue between sophisticated and ordinary ideas that, for Fiat, helped them to rethink some of their own organizational routines and paradigms.

Lessons Learned

For executives of Fiat Brazil, the project brought valuable lessons:

- An external collaboration process cannot function effectively without an organizational willingness to adapt. The collaborative process established outside the company required an in-house collaborative mindset across several departments, such as R&D, design, engineering, marketing, and communication. Every team was eager to hear what Internet users had to say.

- The need to leave out some good ideas was a source of frustration for both the organization and the crowdsourcing participants. Many of the ideas were mutually exclusive; it would have been impossible to act on every good suggestion. In projects with high levels of participation and many good suggestions, many contributors can become frustrated if their ideas are not included.

- The product may not be the real outcome. Some executives realized that the prototype itself was almost not relevant. Instead, it represented the outcome of a lively discussion, a relationship built between Fiat and its consumers that, ultimately, made Fiat learn how to better communicate with people, by also assimilating their knowledge. Perhaps the most meaningful legacy of the Fiat Mio is the communication platform built between Fiat and consumers and the large amount of data that Fiat collected from the crowd. The organization also obtained synapses, links, solutions, and new ways of working that they never would have developed on their own.

- The Fiat Mio project gave the company new perspectives on problems and caused them to rethink some of their paradigms. According to a Fiat executive: “When we have simplistic and naive points of view about something that has become deeply technical and complex for us, we have undergone a kind of disconnection; and I think this is a good thing.” On the other hand, Internet users were enthusiastic about co-creating a crowdsourced car. As one participant said: “That’s it! It’s Mio! If the idea came from you, if you have participated, even from the outside, you feel like you’re in the factory working.” Many of the participants also became briefly well-known as being the owner of a specific idea materialized in the prototype.

Conclusion

In this article, we aimed to present how Fiat managed a large crowdsourcing project to create a concept car and also filled a gap in the crowdsourcing literature, because very few studies, if any, have reported a large crowdsourcing project in the automobile industry. We presented the accordion model, which revisits the classical stage-gate model by proposing a non-linear funnelling development. This new approach includes the presence of a lively community of users, which enables a rich and iterative dialogue between experts and lay people, the “the sacred and the profane”. As with any emergent phenomenon, other processes and characteristics of crowdsourcing are still barely known, which provides a vast field of subjects for further research.

From the lessons learned by the case, future research should focus on how the organizational structure may change prior to or after a crowdsourcing project. For instance, a need to engage knowledge brokers may arise, as was seen in this case when Fiat engaged its advertising agency into the core of the project. It would also be relevant to understand how to take advantage of the likelihood that some experts may emerge from the crowd: how crowdsourcing could be eventually seen as a recruitment tool. As each phase is constrained and enabled by choices that were made in a previous phase, it would be equally important to further investigate how to deal with crowd frustration before it may turn against the organization, which may trigger the so-called crowdslapping effect (Brabham 2009) if many ideas are not used. Finally, another field of research should investigate how to quantify the “legacy” of a crowdsourcing project in terms of the amount of the consumer data collected for the future development of products or services. We believe that the accordion model is indeed adjustable and applicable to other sectors of the industry, given that its phases demonstrate the steps to follow in a crowdsourcing project. Future research could also validate empirically the application of this proposed model.

Acknowledgements

This study was developed thanks to the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council through the Ideas Generation Project, and by the Canadian Space Agency through the Open Innovation Research Project.

References

Bayus, B. 2013. Crowdsourcing New Product Ideas over Time: An Analysis of the Dell IdeaStorm Community. Management Science, 59(1): 226-244.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1599

Brabham, D. C. 2008. Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases. Convergence, 14(1): 75-87.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1354856507084420

Brabham, D. C. 2009. Crowdsourcing the Public Participation for Planning Projects. Planning Theory, 8(3): 242-262.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1473095209104824

Chesbrough, H. W. 2003. The Era of Open Innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring: 36-41.

Cooper, R. G. 1990. Stage-Gate Systems: A New Tool for Managing New Products. Business Horizons, 33(3): 44-54.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(90)90040-I

Cooper, R. G. 2006. The Seven Principles of the Latest Stage-Gate Method Add Up to a Streamlined, New-Product Idea-to-Launch Process. Stage-Gate International. September 1, 2014:

http://www.stage-gate.net/downloads/working_papers/wp_23.pdf

Huston, L., & Sakkab, N. 2006. Connect and Develop: Inside Procter & Gamble's New Model for Innovation. Harvard Business Review, 84(3): 58-66.

Jarvis, J. 2009. What Would Google Do? New York: HarperBusiness.

Lafferty, J. 2012. Lay’s Joins Growing Trend of Brands Crowdsourcing Through Facebook. AllFacebook. September 1, 2014:

http://allfacebook.com/lays-crowdsourcing-chips_b95110

Langley, A. 1999. Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4): 691-711.

http://dx.doi.og/10.5465/AMR.1999.2553248

Le Masson, P., WEIL, B., & Hatchuel, A. 2006. Le processus d’innovation: Conception innovante et croissance des entreprises. Paris: Lavoisier.

Prahalad, C.K., & Ramaswamy, V. 2004. Co-creation Experiences: The New Practice in Value Creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3): 5-14.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

Sartre, J.-P. 1985. La critique de la raison dialectique, Tome I. Éditions Gallimard.

Silva, A. 2010. Fiat Mio: A História de uma Revolução (The Story of a Revolution). Sao Paulo: Agência ClickIsobar.

Smith, S. 2003. The Constraining Effects of Initial Ideas. In P. Paulus & B. Nijstad (Eds.), Group Creativity: Innovation through Collaboration. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195147308.003.0002

Smith, D., Manesh, M. M. G., & Alshaikh, A. 2013. How Can Entrepreneurs Motivate Crowdsourcing Participants? Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(2): 23-30:

http://timreview.ca/article/657

Stake, R. E. 1998. Case Studies. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.). Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry: 445-454. California: Sage Publications.

Wentz, L. 2009. At Fiat in Brazil, Vehicle Design Is No Longer by Fiat. Advertising Age, September 1, 2014:

http://adage.com/article/global-news/fiat-turns-social-media-consumers-c...

Keywords: automobile industry, Brazil, crowdsourcing, Fiat, marketing, Open innovation, project management