AbstractHaving an office in China, we have advantages in the ability to develop games cheaply and the ability to develop games rapidly. The China office is very efficient in terms of speed.

Interviewee and manager of an online game company

This article examines the rapidly-growing online game industry in China, which is a prime example of the changing regional landscape of new creative industries in East Asia. The industry’s evolution in China demonstrates the complexity of the growth of this industry through various knowledge and production networks. Despite the fact that Chinese companies were initially a second mover in this industry and had limited technological competence, they managed to move up the value chain within a few years, from operators of foreign-developed games to game developers. The catch-up process in this creative industry has differed from traditional manufacturing industries, which reflects the responsiveness and close proximity between product and service as key elements of the online game experience. This article conceptualizes this product–service offering in the industry and highlights its requirement for a widespread geographical network, as well as close proximity and responsiveness between elements of the network. In the empirical study of the growth of the Chinese online game industry described here, we argue that Chinese companies have managed to grow by utilizing the strategic control of service, player preferences, and responsiveness in this network, and translating this control into constant incremental improvement of their game development offering.

Introduction

With technical abilities and strong innovation systems, countries can gain competitiveness in economic development (Lundvall et al., 2006; Masuyama & Vandenbrink, 2003). The rapid economic growth of countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia is pushing these economies towards a situation where services and creative industries make an increasing contribution a greater contribution to gross domestic product (Daniels, 2005; Ström & Mattsson, 2006; UNCTAD, 2008).

Since the mid 2000s, there has been a global shift in the geography of production in the creative industry. While established centres of creative industry production in the United States, Japan, and Europe remain strong in creative industries, new regions have focused on the opportunities in newly emerging creative sectors. As a result, “…new forms of cultural production are expanding rapidly in what until recently was commonly referred to as the ‘periphery’ of global capitalism” (Lorenzen et al., 2008). In East Asia, one of the most interesting creative sectors to exemplify this global shift is the rapidly growing online game industry, where technology-intensive services are prominent. There are two main types of online game: i) massively multiplayer online games (MMOG) and ii) casual online games. In MMOG, which initially dominated the market, thousands of people can play a game simultaneously in virtual worlds on computer servers, often over the course of many months. Usually, casual online games are less complex than MMOG and are played on social networks, browsers, and mobile phones. Some of the most successful MMOG have over one million active players, but due to server capacity limitations, they may be distributed over a number of server database partitions, or shards, in different geographical regions.

Revenues for the worldwide online game market in 2012 were estimated at $21 billion USD (DFC, 2013). Japan has traditionally been the East Asian industrial leader in game software for video games, arcade games, handheld games, and mobile phone games (Johns, 2006; Izushi & Aoyama, 2006). However, since the late 1990s, the new online game industry has been the most rapidly-growing segment of the global game industry (Lehdonvirta & Ernkvist, 2011). In the online game sector, the regional leadership of Japanese game companies has been challenged by new companies from Korea and China. Even by 2009 the online game markets in Asia outside of Japan account for over half of the worldwide online game market (Lehdonvirta & Ernkvist, 2011). Korea was initially the largest market in the region, but through rapid growth in recent years, China has become the largest market. The market size for Chinese game market increased to 83.17 billion RMB in 2013 ($13.4 billion USD). Online games dominated the market, with the largest segment being PC online games (53.66 billion RMB), followed by browser-based games (12.77 billion RMB), mobile phone games (11.29 bn RMB), social network games (5.41 billion RMB), and single player games (0.9 billion RMB) (GPC, 2014). In total, an estimated 338 million users were accessing online games though personal computers and 225 million users accessing online games though mobile phones (CNNIC, 2014). Online games have become the focus of "cultural consumption" by China’s younger generation.

The regional shift that has taken place in the supply side of the industry is just as interesting as the demand-side shift. The supply side has been characterized by increasing competitiveness of domestic Chinese online game companies from the private sector. Initially, Chinese game companies were predominately service operators for online games that had been developed by foreign, mostly Korean, online game developers (Chung & Yuan, 2009; Ernkvist & Ström, 2008; Ren & Hardwick, 2009). However, over time, the revenue share of Chinese-developed games in the domestic market has increased, from around 15 percent in the early stages of the industry in 2003 (iResearch, 2005) to a level of 60 to 65 percent (Table1). The recent international expansion during this period represent a new focus of China as an exporter in new emerging creative industries.

Table 1. Chinese market for domestically developed games and export

|

Year |

Market Size of Domestically Developed Games |

Market Size of Foreign-Developed Games (bn RMB) |

Share of Domestically Developed Games (% of total market revenues) |

Chinese Game Export (bn RMB) |

|

2005 |

2.26 |

1.51 |

60% |

– |

|

2006 |

4.24 |

2.3 |

65% |

0.04 |

|

2007 |

6.88 |

3.68 |

65% |

0.06 |

|

2008 |

11.01 |

7.37 |

60% |

0.07 |

|

2009 |

16.52 |

9.10 |

65% |

0.11 |

|

2010 |

19.30 |

13.07 |

60% |

0.23 |

|

2011 |

27.15 |

15.70 |

63% |

0.36 |

|

2012 |

368.10 |

– |

– |

0.57 |

|

2013 |

476.60 |

– |

– |

1.82 |

Sources: CGPA (2009), GPC (2014)

In general, the online game industry is characterized by a few games comprising the majority of the market, a relatively complex and time-consuming development process, and operational service of successful games spanning over many years after initial release (Castronova, 2005; Hosoi, 2004; KGDI, 2006; Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003). Revenues in the industry are typically derived from business models that are based on time or virtual items.With time-based business models, revenues are either derived through monthly, flat-fee subscriptions or through fees based on the amount of time users spend playing the game. With business models based on virtual items, the basic functions of the game are free for the players, but revenues are derived from the sales of virtual items and services within the game.

In China, the creative industry is now the target of increasing interest from private industry and policy makers that had earlier earlier had been concentrated in the manufacturing sectors around the processes of development and economic growth (Hartley & Keane, 2006; Hartley & Montgomery, 2009; Keane, 2007; O’Connor & Xin, 2006). With the growth of the knowledge economy and related services, the creative and cultural industry is seen as a sector of potential growth both in terms of employment and economic contribution, and it is seen as a way for China to transform its material productivity, mainly from manufacturing into innovative productivity in knowledge-intensive sectors (Ernkvist & Ström, 2008; Keane, 2007). Despite the rapid growth of the online game industry in East Asia, the geographical dynamic and industrial development of this new sector of the creative economy in China has thus far received limited attention in academic studies. Some of the few exceptions include Chun and Yuan (2009), who have studied the industry through a Porter framework; Ren and Hardwick (2009), who have analyzed the strategic alliances of foreign game companies with Chinese online game companies; Ernkvist and Ström (2008) and Cao and Downing (2008), who have studied the political economy of the Chinese online game industry; and MacInnes and Hu (2007), who have focused on business models in the industry. However, studies have not yet focused specifically on the how Chinese companies have managed to increase their competitiveness in this creative industry, taking into account how the specific industry context (i.e., the development and service of online games) has shaped this development. As China struggles to strengthen its presence in more creative industry sectors, a closer study of the online game industry, which is at the forefront of this development, could give insights into the dynamics, challenges, and underlying reasons behind this regional shift in the geography of creative industries.

For research to contribute to the conceptualization and understanding of creative industries, “...strategic knowledge in the cultural industries must be situated in the analysis of particular organisational fields; not simply imported from other sectors or industries” (Jeffcutt & Pratt, 2002). The aim of this article is to make a contribution to the conceptualization and empirical understanding of the online game industry and its rapid growth in China. In terms of conceptualization, the aim is to outline the specific organizational field of the online game industry – the network of different actors in the industry and the specific requirements for development, operational service, and consumption of online games in China. In terms of empirical understanding, we seek to answer two major questions in relation to the development of the Chinese online game industry:

- What have been the specific factors behind the rapid growth of the online game market in China since 2001?

- What specific conditions for the increasing competitiveness of domestic companies in the Chinese online game industry have enabled them to increase their development competence?

By combining conceptual and empirical understandings, we aim to study the industry´s growth on a broader scale by examining the complexity of the product and service interaction at the firm-level, an area which we argue is vital for the market acceptance of an online game. The article is based on a number of primary and secondary sources, including interviews with representatives of East Asian game companies and industry actors, governmental reports, company annual reports, company conference calls, and industry reports from analysts.

Online Games: A Complex Creative Industry

Previous research has outlined the conditions for development of video games and offline computer games (e.g., Aoyama & Izushi, 2003; Johns, 2006; Tschang, 2005). However, an online game is different in the sense that it is not a packaged good that is finished after development; rather, it is constantly refined and expanded over several years after the launch. Hence, the game is highly dependent on the operational service capabilities of the game company. The rapid technological change characteristic of the industry and complex product and service interaction call for a holistic network approach in order to capture the development of the industry. The network approach has been developed and used in studies on how companies connect to each other through activity links, resource links, and actor bonds (Håkansson & Snehota, 1995). Although the network approach has been mainly applied to manufacturing, attempts have also been made to extend the approach to service-oriented industries (Bryson et al., 1993; de Vries, 2006; Sharma, 1991; Ström, 2004). Being a newly established and growing industry, the online games industry relies heavily on the network-based approach with a mixture of activities, resources, and actors.

Earlier studies of creative industries have focused on analyzing the employment structures (Power, 2002; Pratt, 1997), structural analyses (e.g. Jeffcutt & Pratt, 2002; Scott, 2004, 2006), and relations between different parts of creative and video game industries (Aoyama & Izushi, 2003; Izushi & Aoyama, 2006) or video game production networks (Johns, 2006). The interconnectedness characterizing many of the creative sectors also exists in the online game industry. Additionally, the online game industry is characterized by urban agglomeration with continued technical and organizational change serving as driving forces (Ernkvist & Ström, 2008). The development of the industry shares many aspects put forward in evolutional economic geography and its emphasis on the nature and evolution of complex network structures that are created on different spatial levels involving companies, individuals, and institutions. (Boschma & Martin, 2010; Glückler, 2007; Maskell & Malmberg, 2007). The fluid coordination environment and tacit dimension of knowledge creation generates spatial structures where local "buzz" is important (Bathelt et al., 2004; Storper & Venables, 2004). Furthermore, the product and service interaction of the industry enhances the relational complexity on different spatial levels. Jeffcutt and Pratt (2002) specifically discuss the complexity of creative industries, arguing that they are characterized by “dynamic contact-zones that are inter-operational and inter-disciplinary – providing a territory that is hybrid, multi-layered and rapidly changing” (Jeffcutt & Pratt, 2002). The uncertainty regarding the market acceptance of creative products means that companies in many creative industries are involved in an interpretative design process in close collaboration with users to determine what combination of design attributes would prove successful (Lester & Piore, 2004). For games, this design approach represents a form of producer-driven co-development process where the game company is involved in an ongoing interpretative design dialogue with the users (Grabher et al., 2008). This design dialogue is more intense and prolonged in the online game industry in which the game is constantly expanded and altered, even after its release, through recurrent expansion packs during the operational lifespan of the game that could last more than a decade.

Nevertheless, the demand environment in the industry and its preferences are difficult for companies to understand and can be highly heterogeneous. Similar to other creative industries, different groups of users have different interpretations of what is considered “cool, beautiful, or exciting” (Lawrence & Philips, 2002). The heterogeneous and complex demand environment of creative industries creates additional challenges in online games within their respective social communities. For online games, successful operation depends on management of the community in order to attract new players and increase the retention of existing players. Bond-based and identity-based attachments to a group have been found to be important aspects of online communities (Ren et al., 2007). These motivations for group attachments are deliberately modified by game companies through game design changes during the development and service of the game. The uncertainty regarding the market acceptance of creative products means that companies in many creative industries are involved in an interactive design process in close collaboration with users to determine which combination of design attributes would prove successful for the online community (Lester & Piore, 2004). For online games, this approach represents a form of producer-driven co-development process where certain user groups act as lead users in an ongoing design dialogue before, as well as after, the launch of the online game service (Grabher et al., 2008; Morrison et al., 2004; von Hippel, 1986). The ongoing dialogue with users during operational service of online games shapes the game companies’ views regarding what constitutes successful performance factors of their games.

Product and Operational Service Interaction of Online Games

<>During the development phase, game companies have the option of either trying to develop a game in-house or license a game developed by an external game developer. For online games developed in-house , companies are reliant on technological as well as creative skills. The development process includes efforts from graphic artists, programmers, game designers, quality assurance personnel, and managers. More complex games, such as the so-called "massively multiplayer online games" (MMOGs), usually have a costly and long development period of two to three years, whereas casual online games are typically less complex and operate under a shorter development time (NCSOFT, 2006; KOGIA, 2008). Employees with extensive experience in developing online games help minimize problems in the complex development process (Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003). In-house game development increases the possibilities for controlling and launching new versions and upgrades of a game, rather than being dependent on licensing agreements. Self-developed games also strengthen the ability of the game company to proactively monitor and counter hacking activities and initiate minor fixes in order to supply a well-operating service experience. Dissatisfaction with game reliability is a major self-reported reason for gamers quitting a game in surveys from China (iResearch, 2005). Self-developed games also enable games and expansion packs to be developed specifically for the preferences of any particular market.

The alternative to in-house game development is to license a game developed by another game company. Usually, this approach requires a substantial upfront licensing fee as well as royalty revenue sharing during operation of the game. Although the upfront licensing fee varies, due to different contracts, the royalty revenue sharing has usually been 20 to 30 percent of revenues for MMOGs, and 20 to 40 percent of revenues for casual games (Shanda, 2008). Although licensing could enable a company to gain access to a game with high technological quality and popular game design, it also exposes the company to some potential operational service problems, which would be more easily handled with an in-house developed game. Usually, the developer of the game retains the source code of the game itself. Game operators who lack access to the source code are reliant on the ability of the developer to update the game and respond to any code and design problems that might arise (Ren & Hardwick, 2009). In our interviews with game companies, the relationship between the game developer and the game operator was considered crucial in order for the operator to rapidly respond to potential problems in the game and to be able to make changes in the game according to the preferences of the local market.

This product and service interaction is evident in the development phase. Game companies often implement design features based on an established notion of user preferences that they have derived from earlier game operation experience. However, the most important part of the product and service interaction occurs during the later part of the development process, when companies carefully adjust their game design and features according to user feedback in alpha and beta testing phases of the game. According to our interview subjects, a game is not launched before the game company is confident that it has made all necessary design changes to meet users’ requests.

Operational Service, Distribution, and Marketing

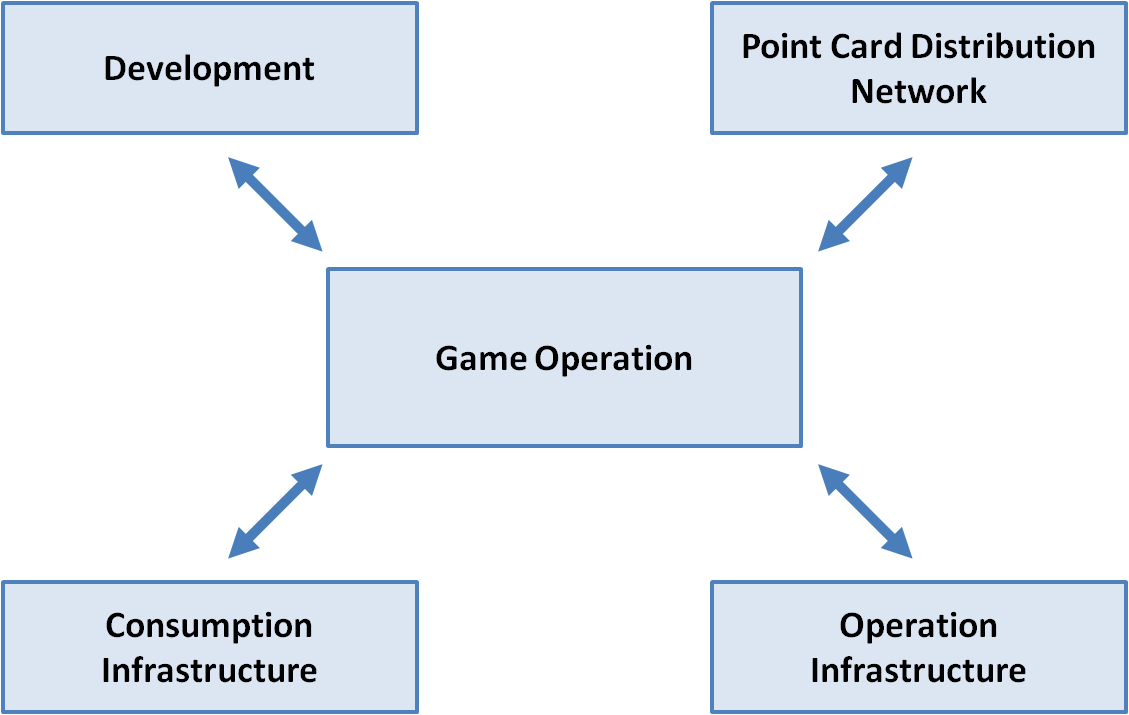

The official launch of a game occurs at the end of the development period after users have provided feedback. Successful online games have a lifecycle of many years after being launched, during which constant service is necessary to retain current users and attract new ones. The network of operating service for games requires seamless interaction between a number of services with different providers, as illustrated in Figure 1 and described in Table 2.

Figure 1. The service network for online games in China

Table 2. Service provider functions for online games in China

|

Function |

Providers |

Services |

|

Development |

External game developer or in-house game development by operator |

· Develop the online game and constantly expand and refine the game design during operation · Fix bugs, cheating and hacks vulnerabilities in the game · Develop new virtual items and services for operator |

|

Point card distribution network |

External game point card distributors or game operator |

· Distribute game point cards that users could use to pay for virtual items and services in the game. · Distribution alternatives: Sales of physical or electronic game point cards through Internet cafés and other venues; sales directly to consumer by credit cards or other payment services |

|

Game operation |

Game operator company |

· Organize special events in the game world to attract players · Service and manage the virtual item trade and economy · 24-hour service to monitor the game and handle player complaints and issues · Various forms of online and offline marketing efforts to attract players · In-game service through game masters · Customer service lines and help desk · Service interaction with other functions: o Constant feedback with external or internal game development function to improve the game, to prevent hacking and cheating, to produce new virtual items and services, and to introduce game expansion packs o Marketing, promotion, and interaction with customers through physical events and Internet cafés o Sales of electronic or physical game point cards through network of Internet cafés or through external distributors o Interaction with provider of technological infrastructure to adapt server and bandwidth requirement with the size of the rapidly changing user base of the game |

|

Consumption infrastructure |

Internet cafés, ISPs, and PCs for consumers. |

· Internet cafés provide a social “third space” for online game consumption |

|

Operation infrastructure (e.g., computer servers, bandwith) |

ISPs, third-party technology providers |

· Provide technological infrastructure for fast and reliable game operation in an environment of a rapidly changing game user base |

Online game companies need to maintain a high level of customer service, and they need to provide constant support in relation to payments, technical issues, and claims. The game company needs to deliver a community service and a sense of belonging to players in order to keep them interested throughout the operational service period. An online community and social interaction for players are as important as the technical abilities of the game. Games should be updated regularly with new content, features, and services in the form of game expansion packs, virtual events, and new game items in accordance with the users’ requirements (Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003; Zackariasson & Wilson, 2004). In such an online community, the motivation for play can be multifaceted. Achievement, relationship, immersion, escapism, and manipulation have all been found to be important user motivations for playing (Yee, 2007). Online games are also important social platforms, with a high proportion of players forming online and offline friendships (Cole & Griffiths, 2007).

This kind of extensive community service is specific to online games and has not been needed in other parts of the game industry. Companies need a specific capacity to deliver services, including close linkages and social relationships with customers and suppliers (Normann, 2000). Innovation in service tends to be continuous and the knowledge creation of service companies is more reliant on the network and tacit know-how gained through interaction with customers whose preferences often are difficult to interpret and poorly specified (Tether, 2005). The ability to create an online game world in which players can enjoy socializing and receive continuous service so they stay and enjoy their game experience is a capability from which leading online game companies derive a large share of their competitive advantages (Fahey, 2005).

A large network of servers is also a prerequisite for game operation. Game companies therefore often use larger external server providers. In order to operate the game cost-efficiently, companies seek to minimize the bandwidth and server requirements of the game, which usually contribute to a significant part of the operational cost of the game, as shown in the annual reports of game companies and a report by Mulligan and Patrovsky (2003).

The financial revenues generated by the games also require an extensive network. The most common way to collect individual game fees in China is still the use of physical game point cards that players purchase, although credit card payments have increased over time, as shown in the annual reports of game companies. The distribution network of these cards through Internet cafés and other market channels is important for a game company to reach as many potential users as possible. Many of the largest Chinese online game companies have created their own distribution networks for game point cards, which have increasingly relied on electronic sales systems at Internet cafés and other distribution points to sell electronic game point cards at higher margins. It has been estimated that the game companies’ distribution costs for physical game point cards are 30 percent of revenues, compared with about 12 percent for electronic sales system and 5 percent for sales directly to the customer through credit card payments (iResearch, 2005). Smaller game companies that lack the resources to create their own distribution networks rely on external game point card distributors in exchange for a share of the revenues (iResearch, 2005). The larger game companies also usually offer a range of games through major game portals, which has the potential advantage of offering economies of scope both in terms of operational service of the games and the marketing and distribution of game point cards. Hence, an integrated service platform could be provided for all the games with cost and quality advantages for customer service.

The Growing Online Game Industry in China

Table 3 describes the factors that have contributed to the rapid growth of the online game industry. The combination of demand-side and supply-side factors have contributed to the growth of the market. On the demand side, the growth of the underlying technological infrastructure for online games, the regulatory landscape of the industry, and the relatively high industry barriers to piracy are factors that have enabled the growth of the industry (Ernkvist & Ström, 2008). On the supply side, factors related to increasing development and operational service competence among Chinese game companies have contributed to the growth of the market.

Table 3. Major factors contributing to the growth of the Chinese online game market

|

Supply-Side Conditions |

Demand-Side Conditions |

|

|

Growth of technological infrastructure

The rapid growth of the broadband infrastructure, personal computers, and Internet cafés in China has contributed to the technological foundation that fuelled the Chinese market for online games (Li, 2003; Qiu & Liuning, 2005). Hence, China’s ambitious information-technology infrastructure plans have, albeit unintentionally, been an important factor behind the growth of the online game market. By 2005, China's personal computer market had become second only to the United States in terms of absolute numbers, with an estimated 67.4 million personal computers in use, although the aggregate penetration in China was only 5.2 per 100 persons by this date (Gartner, 2006).

Internet cafés provide an important venue for online game consumption and, initially, were the single dominating consumption venues for online games in China. They provided cost-efficient access to online games for many young adults, but were also considered important social “third spaces” besides home and school/work in which users can play the games without the control of parents and at the same time socialize with friends (Liu, 2009). Although increasing household penetration of personal computers has intensified competition, and regulation has tightened in recent years, Internet cafés still provide an important venue for consumption of online games (CNNIC, 2009, 2014; Liu, 2009; Qiu & Liuning, 2005).

Reduced piracy and regulatory obstacles

Before online games, companies developing games in Chinae ncountered difficulties due to the presence of legal obstacles and piracy. Console video games have never been able to grow due to a Chinese regulation that makes them illegal. Although offline games for personal computers are legal, the high levels of piracy have been a barrier to development of a domestic industry and the market value for offline games has remained low.

The games themselves reside on costly servers, which make piracy more complicated. Moreover, barriers are also higher because the games themselves involve considerable operational service elements from the game operator, something that piracy servers have more difficulty in offering. Some piracy servers for online games exists, but our interview subjects reported that their impact on the market has been relatively limited so far.

Understanding the legal position of online games in China has also been a prerequisite for growth. The Chinese government has imposed several forms of regulation regarding the design of the games themselves and their services since the inception of the industry. The Chinese government has sought to create a strong domestic online game industry through the use of industry policies that are often ambiguous, and at the same time, government officials have expressed concerns about the societal, cultural, and political consequences of online games (Ernvist & Ström, 2008). Due to a techno-nationalistic policy to strengthen the control of the new medium, and the growth of domestic game companies, foreign companies are not allowed to operate online games in China. Foreign investors are prohibited from owning more than 50 percent of the equity of a Chinese entity that provides content services on the Internet (The9, 2006). Combined with governmental regulatory licensing procedures for online games in China, which have often favoured domestic game companies, this techno-nationalistic policy has supported the transition towards an increasing share of domestically-developed online games in China.

Increasing development and operational service competence

The catch-up process of Chinese game companies is difficult to understand without considering the interaction of online game products and services. Due to Chinese regulations, foreign companies are not allowed to operate online games in China and must make money through licensing or joint ventures with local Chinese game operators. Compared to Korean and other foreign online game companies, many new Chinese game companies were initially far behind in terms of development capabilities, although they are quickly acquiring capabilities in operating and servicing online games. In recent years, this gap in development capabilities between Chinese and foreign companies has been decreasing (iResearch, 2005; Pacific Epoch, 2006).

The growth of domestically-developed Chinese online games that followed was the result of both a technological catch-up process over time, as well as the ability of these companies to turn their operational service skills and knowledge of the local market into a competitive advantage. As a result of the catch-up and expanding Chinese market, the annual reports of leading Chinese online game companies reveal rapid growth in revenues and increasing export in recent years.

Competition to attract the best creative and technically skilled employees is fierce in this environment and employee movement between companies is high. As a newly emerging industry, game developers have been highly focused on the emerging, young creative class in China. A survey from 2007 revealed that the average ages within Chinese game companies were 26 years for employees, 28 years for middle managers, and 30 years for CEOs (Sina, 2008). In order to attract and retain the best talents, several companies offered stock options for key development personnel. The salaries for more advanced development positions such as programmers, producers, and designers are high in relation to the income levels of other industries in China’s metropolitan areas. The lack of experienced game developers was also visible in many of the first efforts by Chinese online game companies to develop their own online games. Several development projects failed and many companies had difficulties developing more technologically complex 3D online games. Over time, the Chinese online game companies increased their experience and some game companies also developed their own proprietary game engines that could speed up the development process. Besides the technological catch-up process, operational service capability has played a key role in the rapidly-increasing competitiveness of Chinese-developed online games. The operational service capability of Chinese online game companies to rapidly respond to market feedback and target local preferences had the effect of increasing the competitiveness of these companies, but this shift towards Chinese-developed online games was accelerated by a shift in the business model for online games. Initially, the online game market was dominated by technologically complex MMOG whose revenues were derived from a time-based model, primarily aimed at dedicated, "hardcore" players. Since 2005, the business model has been making a gradual shift towards more casual online games that generate revenues from the sales of virtual items and services in the game. The business model continued to flourish, but Chinese regulation regarding controversial gambling-related aspects of the model have been developed over time (Ernkvist & Ström, 2008).

Conclusion

The fast-growing online game industry has rapidly become one of the most important sectors within creative industries in Asia during the last decade. The rapid growth of the domestic Chinese online game industry is a perplexing development that is in sharp contrast to the relatively weak competitiveness of China in other creative industries.

In outlining the conditions for the growth of the Chinese online game industry, we have analyzed the industry’s development and the value chain of online games, which has become increasingly complex. This complexity stems from the required interrelation between product development and services in online games, which demands a clear strategy and distinct capabilities both in the area of product development and in determining which services are required to develop, launch, and operate a successful game. The core of the service offering is the ability to constantly develop and support the social community in the game, while product development of the game itself requires access to both technological and creative skills.

The complex product and service interaction of the online game industry means that it is highly vulnerable to disruptions that result in interruption in the interaction of the two parts. A technologically sophisticated game will still fail commercially if it has problems in the operational service, or if the game itself is not continually expanded according to the demands of its heterogeneous player base. Although Chinese online game companies initially lacked competitiveness in the technological aspects of product development, they now enjoy a competitive advantage in the operational service aspects of online games. This competitive advantage refers to both the geographical reach of their service operations and their ability to interpret and respond to the evolving and heterogeneous demand preferences for online games in China. The close relationship between product development and service offering of the company was a prerequisite for the games that were designed from the beginning to be constantly developed according to the interpretation of the users’ changing and heterogeneous preferences.

It remains an area for future research to determine if the online game industry has been a special case in China, or whether this catch-up strategy can be applied to other creative industries as well. What this industry case suggests is that the geographical service network of domestic Chinese companies creates an ability to respond to and interact with users that could provide them with tacit knowledge and comparative advantages in development, even if they have a comparative disadvantage in production technology. Although this approach might not be applicable to all creative industries to the same degree as in online games, the role of user participation and social networks has increased in many creative sectors during the last decade. The increasingly important role of users as co-developers in creative industries and the intensive knowledge flow between users and producers that characterizes many new creative industries might imply that elements of the catch-up process in the online game industry is applicable to other creative industries as well.

This research has necessitated the closer analysis of the industry network that connects the interaction of product development and service operations in the evolution of new creative industries. Research that focuses only on supply conditions in the development of creative products might overlook the role of access to and interaction with the local and heterogeneous market for the development of creative industries over time. Given that this study is an initial attempt to increase the understanding of the growth of the Chinese online game industry, further research on this rapidly-expanding sector of the creative industry in Asia is needed.

References

Aoyama, Y., & Izushi, H. 2003. Hardware Gimmick or Cultural Innovation? Technological, Cultural, and Social Foundations of the Japanese Video Game Industry. Research Policy, 32: 423-444.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00016-1

Boschma, R., & Martin, R. 2010. The Aims and Scope of Evolutionary Economic Geography. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography (PEEG) 1001, Utrecht University, Section of Economic Geography.

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. 2004. Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge Creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28: 31-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

Bryson, J.R., Keeble, D., & Wood, P. 1993. Business Networks, Small Firm Flexibility and Regional Development in UK Business Services. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5: 265-277.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08985629300000016

Cao, Y., & Downing, J. 2008. The Realities of Virtual Play: Video Games and Their Industry in China. Media, Culture & Society, 30(4): 515-529.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0163443708091180

Castronova, E. 2005. Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

CGPA. 2009. “年中国游戏产业报告摘要版” [China Gaming Industry Report]. Beijing: IDC and China Game Publishers Association.

CNNIC. 2009. Statistical Survey Report on the Internet in China. Beijing: China Internet Network Information Center.

CNNIC. 2014. Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Beijing: China Internet Network Information Center.

Chung, P., & Yuan, J. 2009. Dynamics in the Online Game Industry of China: A Political Economic Analysis of its Competitiveness. Revista de Economia Política de las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación, 11(2).

Cole, H., & Griffiths, M. 2007. Social Interactions in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Gamers. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(4): 575-583.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9988

Daniels, P.W. 2005. Services, Globalization, and the Asia Pacific. In Daniels, P.W., Ho, K.C., & Hutton, T.A. (Eds), Service Industries and Asia-Pacific Cities: New Development Trajectories. New York: Routledge.

DFC. 2013. DFC Intelligence Forecasts Worldwide Online Game Market to Reach 79 Billion by 2017. DFC. May 1, 2014:

http://www.dfcint.com/wp/?p=353

Fahey, R. 2005. Interview: NCSOFT President and CEO TJ Kim. May 1, 2014:

http://www.gamesindustry.biz/feature.php?aid=13751

Ernkvist, M., & Ström, P. 2008. Enmeshed in Games with the Government: Governmental Policies and the Development of the Chinese Online Game Industry. Games and Culture, 3:98-126.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1555412007309527

Gartner. 2006. Emerging vs. Mature: Market Classification by PC Will Drive Efficient Sales Growth. Gartner Research.

Glückler, J. 2007. Economic Geography and the Evolution of Networks. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 619-634.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm023

GPC (China Game Publishers Association Publications Committee). 2014. 年中国游戏产业报告摘要版 [China Gaming Industry Report]. GPC.

Grabher, G., Ibert, O., & Flohr, S. 2008. The Neglected King: The Customer in the New Knowledge Ecology of Innovation. Economic Geography, 84(3): 253-280.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.tb00365.x

Harltley, J., & Keane, M. 2006. Creative Industries and Innovation in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(3): 259-262.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367877906066872

Hartley, J., & Montgomery, L. 2009. Creative Industries Come to China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 2(1): 1-12.

Hosoi, K. 2004. Business Model of Successful Online Games: Research on Video Games as "Digital Art Entertainment" Project. Kyoto Graduate School of Policy Science, Ritsumekan University.

Håkansson, H., & Snehota, I. 1995. Developing Relationships in Business Networks. London: Routledge.

iResearch. 2005. China Online Game Research Report 2004. Shanghai: iResearch. May 1, 2014:

http://english.iresearch.com.cn/html/Default.html

Izushi, H., & Aoyama, Y. 2006. Industry Evolution and Cross-sectoral Skill Transfers: A Comparative Analysis of the Video Game Industry in Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning A, 38: 1843-1861.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/a37205

Jeffcutt, P., & Pratt, A.C. 2002. Editorial: Managing Creativity in the Cultural Industries. Creativity and Innovation Management, 11(4): 225-233.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8691.00254

Johns, J. 2006. Video Games Production Networks: Value Capture, Power Relations and Embeddedness. Journal of Economic Geography, 6: 151-180.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi001

Keane, M.A. 2007. Created in China: The Great New Leap Forward. London: Routledge.

KOGIA. 2008. White Paper on Korean Games. Seoul: Korea Game Industry Agency.

Koo, S. 2006. Attack of the Clones. Gamasutra. May 1, 2014:

http://www.gamasutra.com/php-bin/column_index.php?story=8399

Koo, S. 2007. 9you, T3 Make Up, Kick Out Homewrecker. May 1, 2014:

http://www.gamasutra.com/php-bin/column_index.php?story=8745

Lester, R., & Piore, M. 2004. Innovation: The Missing Dimension. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Lawrence, T.B., & Phillips, N. 2002. Understanding Cultural Industries. Journal of Management Inquiry, 11(4): 430-441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1056492602238852

Lehdonvirta, V., & Ernkvist, M. 2011. Converting the Virtual Economy into Development Potential: Knowledge Map of the Virtual Economy. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Liu, F. 2009. It Is Not Merely about Life on the Screen: Urban Chinese Youth and the Internet Café. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(2): 167-184.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676260802590386

Lorenzen, M., Scott, A.J., & Vang, J. 2008. Editorial: Geography and the Cultural Economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(5): 589-592.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn026

Lundvall, B-Å., Intarakumnerd, P., & Vang, J. 2006. Asia’s Innovation Systems in Transition. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

MacInnes, I., & Hu, L. 2007. Business Models and Operational Issues in the Chinese Online Game Industry. Telematics and Informatics, 24(2): 130–144.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2006.04.002

Maskell, P., & Malmberg, A. 2007. Myopia, Knowledge Development and Cluster Evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 7: 603-618.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm020

Masuyama, S., & Vandenbrink, D. 2003. Towards a Knowledge-based Economy, East Asia’s Changing Industrial Geography. Singapore: ISEAS.

Morrison, P.D., Roberts, J.H., & Midgley, D.F. 2004. The Nature of Lead Users and Measurement of Leading Edge Status. Research Policy, 33: 351-62.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2003.09.007

Mulligan, J., & Patrovsky, B. 2003. Developing Online Games: An Insider’s Guide. Indianapolis: New Riders Publishing.

NCSOFT. 2006. NC Soft IR Report August 2006. May 1, 2014:

http://www.ncsoft.net

Normann, R. 2000. Service Management: Strategy and Leadership in Service Business, 3rd edition. Chichester: Wiley.

O’Connor, J., & Xin, G. 2006. A New Modernity, The Arrival of ‘Creative Industries’ in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(3): 271-283.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367877906066874

Pacific Epoch. 2006. Online Game Report 2006. May 1, 2014:

http://www.pacificepoch.com/

Power, D. 2002. Cultural Industries in Sweden: An Assessment of Their Place in the Swedish Economy. Economic Geography, 78:103-27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2002.tb00180

Pratt, A.C. 1997. The Cultural Industries Production System: A Case Study of Employment Change in Britain 1984-91. Environment and Planning A, 29: 1953-74.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/a291953

Ren, Y., Kraut, R., & Kiesler, S. 2007. Applying Common Identity and Bond Theory to Design of Online Communities. Organization Studies, 28(3): 377-408.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840607076007

Ren, Q., & Hardwick, P. 2009. Analysis of Strategic Alliance Management – Lessons from the Failure of Korean and Japanese Licensed Games in China. International Journal of Chinese Culture and Management, 2(1): 1-14.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJCCM.2009.023596

Scott, A. 2004. Cultural-Products Industries and Urban Economic Development, Prospects for Growth and Market Contestation in Global Context. Urban Affairs Review, 39(4): 461-490.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1078087403261256

Scott, A. 2006. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Industrial Development: Geography and the Creative Field Revisited. Small Business Economics, 26: 1-24.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-004-6493-9

Shanda. 2008. Annual Report 2007, 20-F SEC Filing. May 1, 2014:

http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1278308/000095010308001729/dp1045...

Sharma, D.D. 1991. International Operations of Professional Firms. Lund: Student litteratur.

Sina (2008): ”从业人员年龄分析”. May 1, 2014:

http://games.sina.com.cn/n/2008-01-07/1700230323.shtml

Storper, M., & Venables, A.J. 2004. Buzz: Face-to-Face Contact and the Urban Economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(4): 351-370.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnlecg/lbh027

Ström, P. 2004. The ‘Lagged’ Internationalization of Japanese Professional Business Service Firms: Experiences from the UK and Singapore. Göteborg: Department of Human and Economic Geography, School of Economics and Commercial Law, Göteborg University, Series B, No. 107, 2004.

Ström, P., & Mattsson, J. 2006. Internationalisation of Japanese Professional Business Service. The Service Industries Journal, 26(3): 249-265.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02642060600570810

Ström, P., & Erkvist, M. 2012. Internationalisation of the Korean Online Game Industry: Exemplified through the Case of NCSOFT. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation, 6(4): 312-334.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJTG.2012.050962

Tether, B. S. 2005. Do Services Innovate (Differently)? Insights from the European Innobarometer Survey. Industry and Innovation, 12(2): 153-184.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13662710500087891

The9. 2006. The9 2006 Annual Report (10K).

Tschang, F.T. 2005. Videogames as Interactive Experiential Products and Their Manner of Development. International Journal of Innovation Management, 9(1): 103-131.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1363919605001198

UNCTAD. 2008. The Creative Economy Report 2008. Geneva: United Nations Commission on Trade, Aid and Development.

von Hippel, E. 1986. Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts. Management Science, 32(7): 791-805.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.7.791

Wirtz, J., Lovelock, C., & Islam, A.K.S. 2002. Service Economy Asia: Macro Trends and Their Implications. Nanyang Business Review, 1(2): 7-18.

de Vries, E.J. 2006. Innovation in Services in Networks of Organizations and in the Distribution of Services. Research Policy, 35:1037-1051.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.05.006

Yee, N. 2007. Motivations of Play in Online Games. Journal of CyberPsychology and Behavior, 9: 772-775.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772

Zackariasson, P., & Wilson, T. L. 2004. Massively Multiplayer Online Games: A 21st Century Service? Proceedings of the Other Players Conference, IT University of Copenhagen, 6-8 Dec.

Keywords: China, Korea, MMOG, network, online gaming, product and service, service innovation

Comments

With business models based on

With business models based on virtual items, the basic functions of the game are free for the players, but revenues are derived from the sales of virtual items and services within the game.

Play happy wheels for free on PC.

https://happywheels3d.com/