AbstractYou can’t expect to just write and have visitors come to you – that’s too passive.

Anita Campbell

Open marketing as conceptualized in this paper refers to how external parties take part in strategic, integrative marketing activities. To distinguish this more recent trend in marketing from traditional meanings of marketing, the paper provides a typology on roles and role keepers in marketing. Four types of roles and role keepers are outlined: marketing as 1) solely being performed by actors in the supplier company communicating offerings, 2) an activity shared among functions of the supplier company, 3) external parties communicating offerings, and 4) external parties contributing to strategic marketing. Using the concept of 'roles' in marketing helps to structure activities and actors - or roles and role keepers - and provides a basis for understanding that marketing results from what is done, not merely from who performs it. The paper underlines how new ways of conducting business also have implications for a company's marketing beyond its borders.

Introduction

When Day and Wensley (1983)described the strategic orientation of marketing, and hence laid the groundwork for strategic marketing as a key concern, they broadened the marketing concept to include functions both inside and outside of a company. They thereby guided people away from simply targeting customers (consumers) as an operational level problem, a view which had dominated earlier marketing studies. Although marketing in recent years has gained more depth and increasingly included resources and stakeholder concerns, strategic marketing ideas still depart from the individual firm and its circumstances. Recent developments in terms of the collaborative economy and open innovation (Ritter & Schanz, 2019; Öberg & Alexander, 2019; Sanasi et al., 2020)denote how parties both internal and external to a company participate in processes that are not only communicative, but which form a company’s strategy (Whittington et al., 2011).

This paper discusses the inclusion of external parties in marketing, which is referred to as open marketing. Open marketing conceptually links to open source software and open innovation (Dahlander & Magnusson, 2005; Gassmann et al., 2010)in its calling. To indicate its strategic approach, open marketing is compared to a more traditional view of strategic (integrative) marketing, and to marketing as communication efforts on company-centric and external-party levels. The purpose of this paper is to provide a typology on roles and role keepers in marketing, and specifically to conceptualize integrative marketing that includes parties external to a company as open marketing. The following research question is addressed: How does open marketing change the traditional view of marketing?

The paper outlines four types of roles and role keepers: marketing as (i) solely performed by actors in a supplier company that communicate market offerings (operational marketing as referred to, for example, by Day & Wensley, 1983, and Jain, 1983), (ii) external parties communicating offerings (word of mouth and social media exposure, for instance, Marshall et al., 2012; Taylor, 2017), (iii) an activity shared among functions of the supplier firm (that is, strategic, integrative marketing, see Kumar, 2015), and (iv) external parties that contribute to shape offerings and participate in strategic marketing activities (open marketing). The paper focuses empirically on the open marketing idea discussing the concept of roles in marketing.

In the organizational buying behaviour literature, the gatekeepers, decision makers, and others who pursue buying activities have already long been widely recognized (Webster & Wind, 1972; Johnston & Lewin, 1996). Their marketing counterparts, however, have not been as well studied (Kjellberg & Helgesson, 2007; Hagberg & Kjellberg, 2010). The current paper adds to our understanding of marketing in how external parties may perform strategic marketing activities. While literature has either included external parties in the marketing communication discussion (social media and word of mouth), and while it has denoted how marketing in supplier companies reaches beyond mere communication aspects through emphasizing strategic or integrative marketing, less is known about external parties’ activities related to strategic marketing.

Hartwick and Barki (1994)along with Jun and King (2008)investigated the role of users in information system development. Moreover, Song and Thieme (2009)explored the role of suppliers in market intelligence gathering. Examples like these are few, however, and when the roles of external parties are included, the specific actors are normally described and more often related to the innovation literature than to marketing research. The present paper includes several external parties in the analysis of strategic marketing. Using the concept of roles in marketing helps to structure activities and actors included in marketing, and also provides a basis to better understand marketing from what is done, rather than merely from who performs it. The paper underlines how new ways of conducting business also have implications for a company’s marketing strategy.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section explains the concept of roles and role keepers, and develops an analytical tool based on these dimensions. Thereafter I present the data collection method, then provide two empirical examples that portray the roles of external parties in strategic marketing, along with a brief analysis. The analysis section includes a discussion of various dimensions of marketing roles. The paper ends with conclusions, managerial implications, and ideas for further research.

Theory

Roles

The concept of a ‘role’ defines a function performed by someone or a description of what someone does (Parsons, 1951; Gross, 1958; Levinson, 1959; Williams, 1969; Turner, 1985). The current literature indicates a distinction between seeing roles foremost as predefined (Turner, 1985; Ashforth, 2001: for example, the role of a customer), or as dependent on the activities performed (Mead, 1934; Blumer, 1969; Klose, 2020: for example, a customer acting as a co-developer of a solution). Such roles as the latter emerge from role keepers acting on circumstances in a given context (Gross, 1958; Williams, 1969; Goffman, 1983; Laverie, Kleine III, & Kleine, 2002; Harnisch, Frank, & Maull, 2011; Schneider & Bos, 2019), thus shaping their role based on temporal and contextual embeddedness.

Roles can be analyzed in terms of role keepers (the predefined role) and role activities (what the party does), showing how a party can hold a predefined role, while also acting a different one (such as the example of a customer co-developing a solution, Öberg, 2010). The literature has addressed role conflicts and ambiguities (Pettigrew, 1968; Miles, 1976; Singh & Rhoads, 1991)based on how parties may act beyond expectations based on their predefined roles, as well as how the expectations of others may conflict with what the role keeper thinks is its expected behaviour. But while the literature has primarily discussed role conflicts, the reality is that both predefined and activity-based roles can be expected to co-exist. Business structures, including company governance, for instance (Pettigrew, 1968; Yapp, 2004), can expect to guide behaviours towards predefined roles, while other contexts may actually promote parties acting beyond their predefined roles. In this paper, the concept of roles refers to activities of parties, while still defining them based on the position they hold in relation to a supplier company. This means that the party holding a predefined role can also act beyond it.

Analytical Framework

Assuming roles can be either predefined or based on activities of parties, this paper discusses these two dimensions and makes a distinction regarding predefined roles (described as role keepers) between actors as part of the supplier firm (that is, the unit whose products or services are marketed), and parties external to that company. The role keepers are in turn described based on their predefined roles vis-á-vis the supplier company, that is, their roles are based on their position relative to another firm (see Freeman, 1984 on various company stakeholders). The paper discusses the activities they pursue as roles related to marketing as communication, as well as in strategic marketing (see Day & Wensley, 1983; Jain, 1983; Pitt & Treen, 2019). Strategic marketing is defined by Varadarajan (2010) as the:

“organizational, inter-organizational and environmental phenomena concerned with (1) the behavior of organizations in the marketplace in their interactions with consumers, customers, competitors and other external constituencies, in the context of creation, communication and delivery of products that offer value to customers in exchanges with organizations, and (2) the general management responsibilities associated with the boundary spanning role of the marketing function in organizations.”

This resembles how the American Marketing Association (2007)underlined that marketing is a company activity, rather than a function performed exclusively by a marketing department (Homburg, Workman, & Jensen, 2000; Mullins, Walker, & Boyd, 2008; Geiger & Finch, 2009). Kumar (2015)refers to this as integrative marketing, which underlines that marketing reaches beyond marketing or sales staff communicating about a product or service to potential customers.

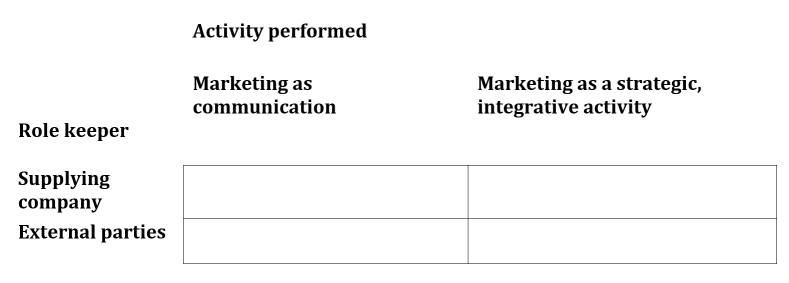

To capture the different dimensions of marketing, the paper thus uses parties’ predefined roles and activities, and distinguishes between the supplier company and external parties, as well as between communication and strategic marketing activities. Figure 1 outlines this framework.

Figure 1. Analytical tool: Roles and role keepers in marketing.

Method

To depict open marketing, I provide two empirical examples below. Their function in the paper is to illustrate various roles in marketing (Siggelkow, 2007), both related to internal and external role keepers and activities pursued. The illustrative function aims to clarify the open marketing concept, rather than claiming to describe all companies’ marketing strategies today. The specific examples were chosen because they represent new, and at the same time quite divergent, ways of working with marketing and marketers. They complement each other in that they demonstrate additional aspects of taking or assigning roles in marketing. For practical reasons, two domestic Swedish examples were selected. Both companies are SMEs, which means that their reliance on external parties for marketing is likely greater than if they were large or international firms. For confidentiality reasons, the companies’ names have been altered.

Data collection

The first example of E-collaboration was studied as part of a thesis, since one of the companies (the IT company) was an external project party for the thesis. During the thesis project, the researcher closely followed the company for three months, investigating customers’ views on customer management systems. Data capturing methods for the research included interviews, participation in informal meetings, and a questionnaire. For this paper, the data collection provided for the thesis was complemented with secondary data including company presentations and a newspaper article review.

In the second example with WebDevelopment, the data collection was based on participatory research (Sarantakos, 1998; Bryman, 2001). The company was studied for four years, including the researcher attending several company meetings per year. In addition to formal and informal contacts with the company owner and participation in business and auditor meetings, I analysed the company’s business plan and other secondary data material specifically for this paper. A secondary data analysis allowed for systematizing the data (Huettman, 1993; Welch, 2000)that had previously been held as informal and non-structured information about the company. It also provided details on the business model and added a broader perspective on external parties and marketing activities. For both examples, primary and secondary data sources allowed the capture of the company’s development from 2006 onwards.

Analysis procedure

The data analysis was processed using a categorization and recombination of data techniques (Glaser, 1992; Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Charmaz, 2000). Specific attention was given to categorizing individual actors’ or companies’ roles, and to deciding whether and how each role contributed to marketing. Extracted roles were labelled in a matrix that connected predefined roles (supplier, intermediate, etc.) with activities performed (see Figure 1). This was done for the individual examples, then during a second step, for the two examples combined. To distinguish between the marketing roles and predefined roles of suppliers, production staff, customers, and so forth, the former is referred to as marketing activities, while the latter is described as predefined functions or role keepers. Analytically, this combines a position-related predefined view on roles with an emergent perspective.

Two Examples

E-Collaboration

E-Collaboration is a joint venture partnership between an IT company and a marketing agency. The IT company started working with the agency because it lacked competencies in communication and marketing, which were considered essential for the systems it develops. Cooperation between them had run for several years, focusing on various projects. The IT company was founded in 1998 to work with small and medium-sized companies in Sweden. The marketing agency, which was founded in 2006, is situated in the same town as the IT company. It consists of two co-owners who are also active in the agency as project and customer manager, and designer, respectively. The two owners work with other marketing agencies and self-employed individuals that provide services in photography, illustration, and copywriting.

The IT company had developed a system for electronic customer interaction management (e-CIM), with the marketing agency as its collaborator. Such a system is like customer relationship management (CRM) solutions in how it organizes and manages a company’s customer base. Yet while a CRM system allows suppliers to collect and systemize customer data, the e-CIM system is also based on mutual interaction between customers and suppliers, where both parties affect what data is actually collected and processed. The system provides marketing tools and builds customer databases, marketing research tools, and implementation for customer communication and response. Through the system, customers impact what products are offered, from design to sales and services. E-CIM solutions also take into account word-of-mouth among customers, and this way passive customers become part of the system, as data is captured from and about potential customers who have not yet made any purchases, based on what they indicate they are looking for.

The specific system developed by the IT company and the marketing agency is directed to shopping centers, nightclubs, and other marketing agencies. The specific aim of the system is for these companies to use it in their interaction with customers: shopping centers visitors, individual stores, night club patrons, and marketing agencies. Marketing agencies also use it in their work with customer companies (those ordering advertising campaigns) and direct customers (those who buy products or services based on the campaigns). They are active in providing data on themselves, their needs and wants, and on what data should be collected for each of these parties. The data is then processed to be used for marketing analyses, thus providing input for wider marketing activities. Shopping centers offer collected data to individual shops, thereby connecting customer input with those who intend to meet customers’ needs.

Looking at the various parties and their roles with E-Collaboration, it seems apparent that both the IT company and the marketing agency work on marketing the eCIM system. Both E-Collaboration companies (the IT company and the marketing agency) offer the system directly to shopping centers and nightclubs, as well as to other marketing agencies. In addition, and related to the broader definition of marketing, consumers at shopping centers and visitors to nightclubs provide information to the eCIM system, with shopping centers and nightclubs acting as customers for such information. The consumers consequently also act as producers in that sense. To complicate the picture further, the party requesting the information (that is, the shopping centers and nightclubs), together with the customers that provide it, impacts what information is collected. Furthermore, shopping centers can provide this service to individual stores in the centers, thus acting as information suppliers to the stores.

WebDevelopment

WebDevelopment was founded in 2006 by a young innovator who had the idea to develop a protective shell for Apple computers. The shell was manufactured from a specific material that would protect the computer, and a great deal of effort was made to design the shell and market it to customers. To give the shell an environmentally friendly niche, a specific plastic consumer package was designed. The idea was that the package could be reused by consumers to create a lampshade. Once that plastic material was found, however, the direction of WebDevelopment’s business changed. While the innovator continued to market the computer shell, operations began to focus on the use and reuse of materials. In addition to the plastic material, other waste products were recycled for new business ideas.

At the time, the innovator also started to collaborate with four other innovators specializing in areas such as product development and design. Together, they created a web-based community for product development built on recycled materials. The core business model consequently came to involve sustainable product development based on community input. External parties were allowed and encouraged to contribute ideas and solutions on how to use the materials provided, as well as how other waste products could be recycled. The innovator and the collaboration partners also established relationships with some fifteen industrial designers and consumer package designers for the purpose of reaching waste materials, accessing design ideas, and collaborating on production and production ideas.

For suppliers of goods, WebDevelopment, its collaborators and users in the web community design and provide solutions for recycling materials. In terms of package materials, goods manufacturers can launch packages as environmentally friendly solutions, thus creating an argument in their product marketing. The package manufacturers in turn use similar arguments with the goods manufacturers. Through partnerships facilitated by the web community, innovators provide package manufacturers with cutting tools to manufacture packages, as reusage sometimes determines how the package is designed in the first place. Package suppliers help to market WebDevelopment’s ideas to goods manufacturers. In addition, manufacturers of both goods and packages showcase their use of recycled material products for marketing purposes, and the innovator enables them to put their brand names on such products. Packages that are recycled into new functions make consumers into producers of new products. Participants in the web community provide new ideas as solutions for how customers can reuse materials. These solutions in turn benefit goods manufacturers, package producers, the companies behind the web community, and consumers.

In addition to packages, the recycling undertaken by WebDevelopment involves other waste products from production. This means that WebDevelopment manufactures or designs goods based on waste material, thus focusing on more than only how consumers can reuse packages. Such waste product solutions are then sold separately through stores. Also, in this product development and design approach, users of the web community contribute ideas, as do manufacturers, collaboration partners, WebDevelopment as a company, and also designers. One innovation that came out of this is a clothespin; another is building blocks made from the waste of formed plastics.

The roles and role keepers in this example include the innovator marketing the ideas of a web community to users and consumers, as well as to potential collaborators. WebDevelopment and its partners also market their products to users, as well as to goods manufacturers and package companies. Users of the web community affect the designs and materials choices, thus contributing to a broader scope of marketing activities that attract additional users, product manufacturers, package producers, and consumers. Manufacturers of goods to be packaged market themselves and also the collaborators and package designers to their customers. In coordination with ideas provided by users and the innovator, manufacturers impact what is produced and also what waste material is available. Package designers are those who market the material to manufacturers of goods to be packaged using the recycled materials. They also contribute with ideas on design and collaborate with the web community on finding solutions. Those offering ideas to the web community are either customers themselves or people who use the web community primarily for reasons connected with creativity.

Analysis

The two examples above illustrate various marketing roles and role keepers. Parties involved (role keepers) include the supplier companies, along with external parties: collaboration partners, direct and indirect customers (that is, customers and customers’ customers), marketing agencies, web users, suppliers to customers, and suppliers’ suppliers. The parties act to communicate the product, provide input for product development and new ideas, decide on ideas to produce, and supply data that is used for the product. Likewise, they act through marketing the product, the companies (E-Collaboration and WebDevelopment), and their products and companies to others. This emphasizes roles that are both related to the communication of offerings and include integrative, strategic marketing activities, such as the creation, delivery, and exchange of offerings, and the maintenance of relationships (Varadarajan, 2010; Kumar, 2015). Hence the roles capture both the resource side and customer interaction side of marketing, as seen in the E-Collaboration example. The activities also extend beyond a party’s impact on product decisions to the dyadic level, and describe how a party decides on products and their design for others. It also blurs the view on who (or whose product or service) is marketed, as seen for instance in the WebDevelopment example, where package and goods manufacturers also marketed themselves through WebDevelopment’s products.

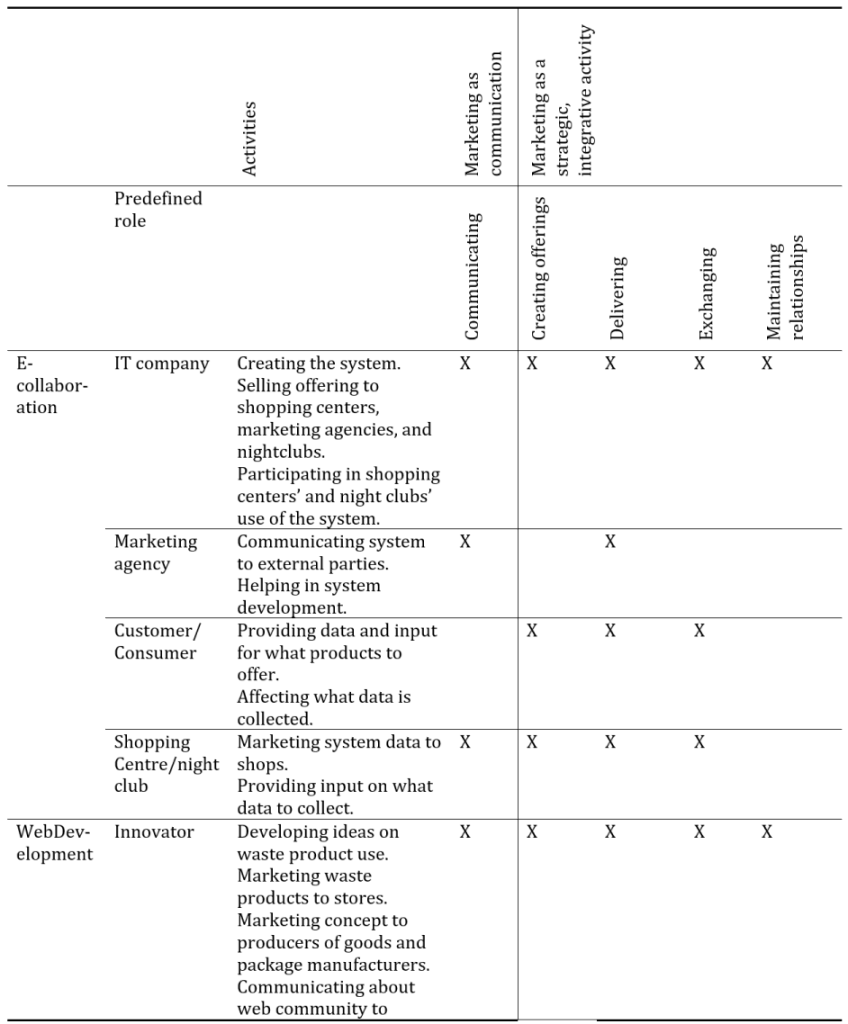

The examples thus demonstrate that roles may be held by supplier firms and external parties. Further, while the ways to conduct business may introduce new role keepers and activities related to marketing, the existing parties also continue with more traditional roles (for example, communications). Table 1 summarizes the marketing roles in the two examples. The division into role keepers and activities follows the framework outlined in Figure 1, while the various activities are inductively captured from the examples. These activities should not be seen as exclusive, but are rather identified to indicate how various parties act within several marketing roles that belong to ‘integrative marketing’, as referred to by Kumar (2015).

Table 1

The two examples above further indicate how a business actor can combine or abandon (Yapp, 2004)a predefined function in the company they work at for an additional temporal role. In many senses, the examples point to how the roles of customers, suppliers, and partners get mixed together. The roles executed include the extensions of predefined functions, parties acting in other roles while remaining with their predefined one, and parties abandoning their predefined function for other roles (see Öberg, 2010 on traditional, added, and transferred roles).

A traditional role in a company describes how the marketing staff of a supplier company markets the company’s products, thus identifying coherence between role keeper and activities performed. Added roles outline how a customer affects the offering provided (Normann, 1991), and also participates in gearing offerings to benefit others, that is, a party acting its expected role while also participating in additional activities. Transferred roles describe how a customer stops being a customer in order to develop products to benefit others, as seen in the WebDevelopment example, and in terms of the shopping center organizations that became suppliers to E-Collaboration, while at other times acting as its customers. Roles defined as activities pursued thus further indicates the coexistence of various roles held simultaneously by a single actor. At the same time, several parties may engage in the marketing role, thus sharing it, not only on the level of performing marketing activities, but also in terms of providing input to shape offerings, for instance, as seen with users of the web community, customers, and the innovator in the WebDevelopment example.

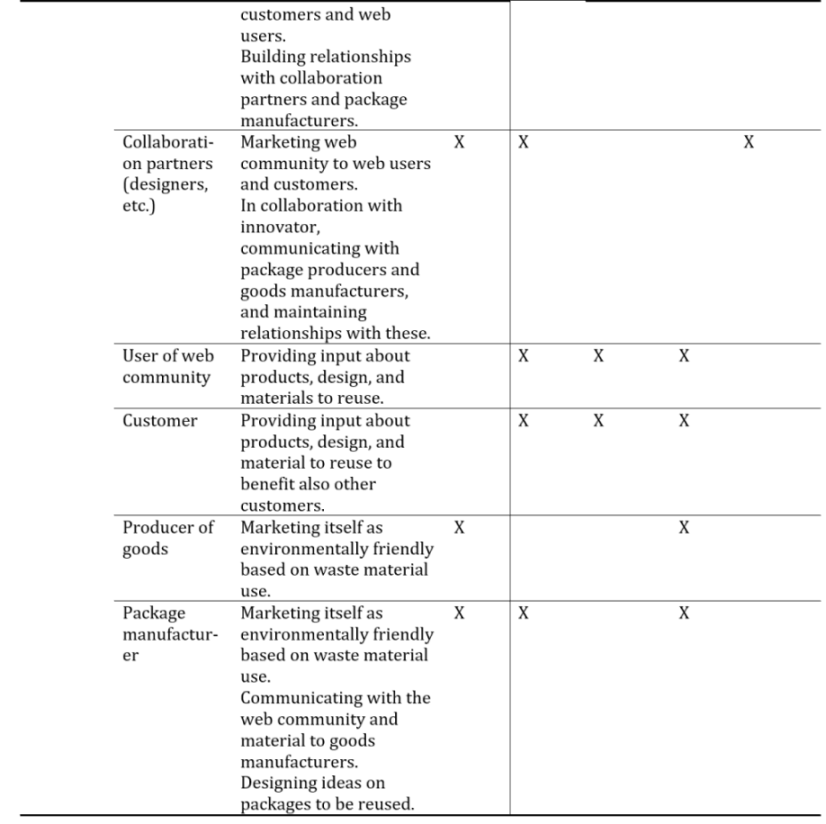

A typology on roles

If returning to Figure 1, a typology of different role keepers and roles can be developed. Marketing can be defined as (i) solely being performed by actors in the supplier company that communicate market offerings (operational marketing as referred to by Day & Wensley, 1983; Jain, 1983); (ii) external parties communicating offerings (word of mouth and social media exposure, for instance, Marshall et al., 2012; Taylor, 2017); (iii) being an activity shared among functions of the supplier firm (meaning strategic, integrative marketing, Kumar, 2015); and (iv) external parties contributing to shape offerings and participate in strategic marketing activities (open marketing). Table 2 summarizes these, to which the discussion below turns.

Table 2

Marketing as communication by supplying firm (operational view)

The operational view of marketing portrays marketers as those communicating a company’s offering. This is how marketing was treated in its early development (Coutant, 1936; Converse, 1945; Bartels, 1951, 1974). It involves marketing as campaigns rather than as integral parts of the company’s operations. It also depicts marketing as operational or tactical, rather than strategic. While marketing and sales staff of supplier firms are central in marketing, there are also, as discussed below, other actors that contribute.

External parties communicating offerings

Early marketing ideas acknowledged intermediates and marketing agencies, and more recently, customers have been seen as communicators of supplier firms’ offerings (Kumar et al., 2007; Taylor, 2017). Marketing can thus be pursued by parties external to a supplier company, where such parties may interact with the supplier company (for example a marketing agency) in campaigns, or share their feedback on the company’s products or services to others in the business ecosystem beyond the actual control of the supplier company (for example customer word of mouth and social media, Marshall et al., 2012; Dessart et al., 2015). This focus is not on an interactive view of marketing, but rather on how external parties participate in marketing to other parties. Word of mouth, for example, denotes that a customer promotes a product or service to other customers (Kuokkanen, 1996; Kumar et al., 2007)in such a way that they act similarly to marketing and sales staff, according to the marketing view described above. The activities that they pursue are communicative in orientation, while as parties in the business ecosystem, they are external to the supplier company. The parties thus act in temporary roles, while still being predefined as customers (and marketing agencies).

Strategic, integrative marketing

When referring to marketing as an integral part of a company (Kumar, 2015), it seems apparent that the role of marketers is shared among various actors in the supplier company. Early literature (Shaw, 1912; Levitt, 1960)depicted marketing activities as being closely related to communication activities. McGarry (1950), for instance, referred to the contractual, merchandising, pricing, propaganda, physical distribution, and termination functions of marketing. Since then, strategic marketing has come to refer to decisions and behaviours related to resource supply, competition, customers and other stakeholders for a company (Pitt & Treen, 2019). Within the company, an integrative view includes staff working on distribution, product, and production, along with service staff, as well as management. This does not, however, mean that everything these parties do counts as marketing. Rather, their roles as marketers relate to specific situations and contexts, constituting more temporal roles.

Open marketing

As described in the previous section activities beyond just communicating business offerings could also be accounted for as marketing (Varadarajan, 2010). When a customer acts as co-producer in services or takes active part in innovation processes, that customer would not be a marketer, because their efforts do not co-produce offerings for others. However, there are situations in which a customer, or other external parties, play a completely different role than as a participant in exchange activities. In these cases, the customer stops being just a customer and instead works on designing the company’s product, for instance.

Research has focused on open innovations (Chesbrough, 2004; Kirschbaum, 2005; West & Gallagher, 2006; De Wit et al., 2007; van de Vrande et al., 2009; Ili et al., 2010)and open source software (Dahlander & Magnusson, 2005). Open marketing echoes the idea of ‘openness’ from these concepts. Yet, open marketing extends the idea of ‘open’ as described in most open innovation literature on inflows and outflows of knowledge, as open marketing is not controlled by a single focal firm. It rather depends on external parties’ active participation in marketing and includes how external parties perform activities that complement what the firm does. It is also different than open source software in being more simultaneous, strategic, integrative, and complex, compared to the often sequential development of open software solutions. Parties in open marketing further include external parties that may not have or intend to have a relationship with the supplier company, such as the web users in WebDevelopment, who were not contracted by any party, and yet provided ideas without being potential customers to the company. Compared with the strategic integrative view of marketing, open marketing increasingly involves parties acting based on their own understanding rather than controls. In the end, there may not be any actual coordination between the different marketing roles.

Thus, in sum, the typology identified above points out complementary, but also alternative ways of considering roles in marketing. These span from traditional to added and transferred roles, from predefined functions to temporal ones, and from coordination by structure to be driven by individual understandings, and reveal roles as both shared and coexistent. Moving from a communications view on marketing to including external parties in strategic marketing reveals that role keepers comprise supplier companies and their collaborators, as well as other external parties that do not intend to have a business relationship with the supplier firm.

Conclusions

The purpose of this paper has been to provide a typology on roles and role keepers in marketing, and specifically to conceptualize integrative marketing that includes parties external to a company as open marketing. The paper distinguished role keepers from the activities pursued by them. We can thus now return to the following question: How does open marketing change the traditional view of marketing? As shown in the paper, open marketing expands marketing both in terms of activities pursued and the types of actors conducting the activities. It means that external parties participate in integrative, strategic marketing, and thereby put focus on both extended roles (Öberg, 2010), and stakeholder participation in marketing.

The implications of open marketing can be thus summarized as follows:

- Within the scope of a predefined role, a role keeper can start fulfilling other activities. Temporary roles may take place together with predefined ones, add dimensions to them, or mean that a predefined role needs to be temporary abandoned for a new role. Open marketing thus increasingly emphasizes the temporality of roles.

- External parties that appear to market offerings have the following predefined functions: parties collaborating with the supplier firm, direct or indirect customers or suppliers to it, or external parties with no actual or intended relationship with the supplier firm. Control over marketing is thus increasingly exchanged for parties that act based on their own understandings. A party may carry out several temporary roles, yet marketing roles may also be shared among several different parties.

Roles in marketing have not been widely researched (Kjellberg & Helgesson, 2007; Hagberg & Kjellberg, 2010). Using the concept of roles in marketing helps to structure marketing activities and actors, and provides a basis for understanding that marketing results from what is done, not merely from who performs it. The theoretical contributions of this paper are as follows: Firstly, the new conceptualizing of ‘open marketing’ is the prime contribution. It captures recent trends in marketing, while also theorizing about the open marketing construct. Secondly, marketing roles can now be seen as more fluid, simultaneous, and shared than previously thought. This enables both researchers and practitioners to expand their current notions of roles, while maintaining that the separation between roles as activities and role keepers helps to create structure as roles become increasingly complex and blurred.

Managerial implications

This paper illustrates various parties’ roles in marketing. It specifically highlights external parties as marketers. Open marketing in this way sheds new light on marketing activities and helps to understand contemporary marketing. Open marketing impacts companies behaviour in the market and in their interaction with others, as well as in creating their offerings, and resource decisions (see Varadarajan, 2010's defintion of strategic marketing). In short, companies need to act much more adaptively in terms of their marketing options. Essentially, a company adopting open marketing becomes an open system with an open marketing strategy.

However, the degree of inclusion of various parties also relates to a company’s business model. To a certain extent, a company can choose to include external parties in its marketing activities, or not. For companies that include external parties, such inclusion may help them reach customers and improve their products. It adds to company strategy and communication.

From a management point of view, designing business models that include external parties or rely on external parties in marketing can positively impact company development and sales. However, including external parties in marketing increases a company’s dependence on such parties, which can serve to make the company more vulnerable. Such vulnerability results from losing part of the control over how the company’s products and services are marketed, and involves a risk that external parties will move the company in an unintended direction, or even promote the company’s products in a negative manner. In addition, and because of competition, certain external parties may make other parties unwilling to enter into business deals with the company. For managers, it is therefore wise to consider what effects various parties’ involvement in marketing may have. A balancing is needed between reaching additional competencies and getting input from users, and the risk of losing sales to other parties. Additionally, there is a simultaneous balancing between control over resources, ideas and communication strategies, and external parties’ willingness to participate.

Further research

This paper illustrated various roles in marketing through two company examples. For further research, it would be of interest to study additional cases, deepen the data collection, and thereby see whether, for instance more studies confirm or add to the findings presented in this paper. In addition, each party’s role could be researched more closely, along with investigating each party’s impact on the marketing and sales of goods or services. Lastly, it would be worthwhile to study the interaction between intra-company and external marketing activities, as well as companies’ decisions to include or exclude external parties in their marketing efforts.

References

American Marketing Association. 2007. Definition of marketing. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

Ashforth, B.E. 2001. Role Transitions in Organizational Life: An Identity-Based Perspective. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Bartels, R. 1951. Can marketing be a science? Journal of Marketing, 15: 319-328.

Bartels, R. 1974. The identity crisis in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 38(4): 73-76.

Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bryman, A. 2001. Social Research Methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Charmaz, K. 2000. Grounded theory - Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc: 509-536.

Chesbrough, H. W. 2004. Managing open innovations. Research Technology Management, 47(1): 23-26.

Converse, P. 1945. The development of the science of marketing - an exploratory survey. Journal of Marketing, 10: 14-23.

Coutant, F. 1936. Scientific marketing makes progress. Journal of Marketing, 1(3): 226-230.

Dahlander, L., & Magnusson, M.G. 2005. Relationships between open source software companies and communities: Observations from Nordic firms. Research Policy, 34(4): 481-493.

Day, G.S., & Wensley, R.J.o.M.F. 1983. Marketing theory with strategic orientation. Journal of Marketing, 47(4): 79-89.

De Wit, J., Dankbaar, B., & Vissers, G. 2007. Open innovation: the new way of knowledge transfer? Journal of Business Chemistry, 4(1): 11-19.

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan Thomas, A. 2015. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: a social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1): 28-42.

Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

Gassmann, O., Enkel, E., & Chesbrough, H.W. 2010. The future of open innovation. R&D Management, 40(3): 213-221.

Geiger, S., & Finch, J. 2009. Industrial sales people as market actors. Industrial Marketing Managment, 38(6): 608-617.

Glaser, B.G. 1992. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

Goffman, E. 1983. The interaction order. American Sociological Review, 48(1): 1-17.

Gross, N. 1958. Explorations in Role Analysis. New York: Wiley.

Hagberg, J., & Kjellberg, H. 2010. Who performs marketing? Dimensions of agential variation in market practice. Industrial Marketing Management, 39: 1028-1037.

Harnisch, S., Frank, C., & Maull, H. 2011. Role Theory in International Relations. New York: Routledge.

Hartwick, J., & Barki, H. 1994. Explaining the role of user participation in information system use. Management Science, 40(4): 440-465.

Homburg, C., Workman, J.P.J., & Jensen, O. 2000. Fundamental changes in marketing organization: The movement toward a customer-focused organizational structure. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4): 459-478.

Huettman, E. 1993. Using triangulation effectively in qualitative research. Bulletin of the Association of Business Communication, 56(3): 42-42.

Ili, S., Albers, A., & Miller, S. 2010. Open innovation in the automotive industry. R&D Management, 40(3): 246-255.

Jain, S. C. 1983. The evolution of strategic marketing. Journal of Business Research, 11(4): 409-425.

Johnston, W., & Lewin, J. 1996. Organizational buying behavior: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Business Research, 35(1): 1-15.

Jun, H., & King, W.R. 2008. The role of user participation in information systems development: Implications from a meta-analysis. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(1): 301-331.

Kirschbaum, R. 2005. Open innovations in practice. Research Technology Management, 48(4): 24-28.

Kjellberg, H., & Helgesson, C.-F. 2007. On the nature of markets and their practices. Marketing Theory, 7(2): 137-162.

Klose, S. 2020. Interactionist role theory meets ontological security studies: an exploration of synergies between socio-psychological approaches to the study of international relations. European Journal of International Relations, 26(3): 851-874.

Kumar, V. 2015. Evolution of marketing as a discipline: What has happened and what to look out for. Journal of Marketing, 79(1): 1-9.

Kumar, V., Petersen, J.A., & Leone, R.P. 2007. How valuable is word of mouth? Harvard Business Review, 85: 139-146.

Kuokkanen, J. 1996. Postpurchase word-of-mouth behavior as a function of consumer dis/satisfaction: A comparison of two explanation models. In P. Tuominen (Ed.), Emerging Perspectives in Marketing. Turku: Turku School of Economics and Business Administration: 91-106.

Laverie, D.A., Kleine III, R.E., & Kleine, S.S. 2002. Reexamination and extension of Kleine, Kleine and Kernan's social identity model of mundane consumption: The mediating role of the appraisal process. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4): 659-669.

Levinson, D.J. 1959. Role, personality, and social structure in the organizational setting. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58: 170-180.

Levitt, T. 1960. Marketing myopia. Harvard Business Review, 38: 45-56.

Marshall, G.W., Moncrief, W.C., Rudd, J.M., & Lee, N. 2012. Revolution in sales: The impact of social media and related technology on the selling environment. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(3): 349-363.

McGarry, E.D. 1950. Some functions of marketing reconsidered. In R. Cox & W. Alderson (Eds.), Theory in Marketing. Chicago: Richard D. Irwin Inc: 263-279.

Mead, G.H. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miles, R.H. 1976. A comparison of the relative impacts of role perceptions of ambiguity and conflict by role. Academy of Management Journal, 19(1): 25-35.

Mullins, J.W., Walker, O.C.J., & Boyd, H.W.J. 2008. Marketing Management: A Strategic Decision-Making Approach (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Normann, R. 1991. Service Management - Strategy and Leadership in Service Business (2 ed.). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Öberg, C. 2010. Customer roles in innovations. International Journal of Innovation Management, 14(6): 989-1011.

Öberg, C., & Alexander, A. 2019. The openness of open innovation in ecosystems - Integrating innovation and management literature on knowledge linkages Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 4(4): 211-218.

Parsons, T. 1951. The Social System. Glencloe: The Free Press.

Pettigrew, A. 1968. Inter-group conflict and role strain. The Journal of Management Studies, 5(2): 205-218.

Pitt, L., & Treen, E. 2019. Special issue of the journal of strategic marketing 'the state of theory in strategic marketing research - reviews and prospects. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27(2): 97-99.

Ritter, M., & Schanz, H. 2019. The sharing economy: A comprehensive business model framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 213: 320-331.

Sanasi, S., Ghezzi, A., Cavallo, A., & Rangone, A. 2020. Making sense of the sharing economy: a business model innovation perspective. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 32(8): 895-909.

Sarantakos, S. 1998. Social Research (2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schneider, M.C., & Bos, A.L. 2019. The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Political Psychology, 40: 173-213.

Shaw, A. W. 1912. Some problems in market distribution. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 26: 703-765.

Siggelkow, N. 2007. Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1): 20-24.

Singh, J., & Rhoads, G.K. 1991. Boundary role ambiguity of marketing-oriented positions: A multidimensional, multifaceted operationalization. Journal of Marketing Research, 28: 328-338.

Song, M., & Thieme, J. 2009. The role of suppliers in market intelligence gathering for radical and incremental innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(1): 43-57.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research - Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Taylor, C.R. 2017. How to avoid marketing disasters: back to the basic communications model, but with some updates illustrating the importance of e-word-of-mouth research. International Journal of Advertising, 36(4): 515-519.

Turner, R.H. 1985. Unanswered questions in the convergence between structuralist and interactionist role theories. In H. J. Helle & S. N. Eisenhardt (Eds.), Perspectives on Sociological Theory. Micro-Sociological Theory. London: Sage Publications: 22-36.

van de Vrande, V., de Jong, J.P.J., Vanhaverbeke, W., & de Rochemont, M. 2009. Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation, 29(6/7): 423-437.

Varadarajan, R. 2010. Strategic marketing and marketing strategy: domain, definition, fundamental issues and foundational premises. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 38(2): 119-140.

Webster, F.E.J., & Wind, Y. 1972. Organizational Buying Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Welch, C. 2000. The archaeology of business networks: The use of archival records in case study research. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 8(2): 197-208.

West, J., & Gallagher, S. 2006. Challenges of open innovation: the paradox of firm investment in opensource software. R&D Management, 36(3): 319-331.

Whittington, R., Cailluet, L., & Yakis-Douglas, B. 2011. Opening strategy: Evolution of a precarious profession. British Journal of Management, 22(3): 531-544.

Williams, D. 1969. Uses of role theory in management and supervisory training. The Journal of Management Studies, 6(3): 346-365.

Yapp, M. 2004. How can "role transition management" transform your company? Industrial & Commercial Training, 36(3); 110-112.

Keywords: Conceptualization, Integrative marketing, Open marketing, roles, Strategic marketing.