Introduction

As with many local public services, childcare is currently witnessing a profound change (Pestoff, 2006). Amid widespread budget cuts, families increasingly need to devise alternative solutions for childcare provision. At the same time, managing work and family life responsibilities is a challenge for working parents, in particular for women, who still carry most of the family work (Ashforth et al., 2000). In order to cope with the increasing challenges of balancing work and family duties, alternative forms of welfare are indeed emerging in the public and private sectors (Osborne et al., 2013). Governments are exploring new forms of partnerships to involve citizens in the provision and governance of public services and to encourage the emergence of workplace initiatives (Hein & Cassirer, 2010; Brandsen, Verschuere & Steen, 2018). Furthermore, forms of public-private initiative for the provision of these type of services are also being encouraged by recent European initiatives (see for example, Barcevičius et al., 2019)

At the same time, new forms of socializing care that leverage community networks and “alternative” social arrangements have been proposed as a viable solution to these challenges, not in view of replacing welfare state provisions, but rather for complementing them. In this changing landscape, the private sector, organizations, and companies, often supported by national or local government Work-Life Balance programs, are promoting new welfare policies. This goes along with family-friendly practices based also on co-participation in order to promote gender equality and retain employees (Connelly et al., 2004; Grosser & Moon, 2008; Lewis, 2018), as part of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives (Carroll, 1999, Wang et al., 2016).

This paper intends to contribute to the ongoing debate on innovative socio-technical practices in organizations by exploring how collaborative childcare services might be deployed in work settings. Our case study targets knowledge-based organizations that are considered one of the key pillars of today’s knowledge economies, while being characterized by flexible working time arrangements and short-term work contracts (Correia de Sousa & van Dierendonck, 2010). Although scholars have provided many different examples of direct contributions by parents to the value created by childcare facilities (Pestoff, 2012), previous studies are mainly focused on traditional forms of co-production, and the potential role of technology in supporting the co-creation of public value has not yet been investigated. In this paper we present a specific case study of an organization experimenting with new forms of collaborative welfare policies. Specifically, the organization implemented some family-friendly practices based on the active participation of employees in co-producing and co-delivering childcare, supported also by digital tools for collaboration and information sharing.

Background

Childcare for working parents and government innovation

Childcare provision is crucial to modern societies and a required step towards equalising opportunities in employment between women and men (Connelly et al., 2004; Lewis, 2018). However, despite the expansion of childcare across the globe, there is further need to provide affordable and flexible childcare services, making childcare more accessible to working parents.

Generally, public authorities are encouraged to “promote” childcare facilities, to develop policies to reduce work-family conflict, and prevent labour market discrimination resulting from family responsibilities (Hein & Cassirer, 2010). However, there are big differences among countries in how much governments and their citizens consider supporting childcare for working parents as a public rather than a private or personal responsibility (Hein & Cassirer, 2010; Pestoff, 2012). In countries where there is little government support for childcare centres, the costs for working parents can be particularly high, thus exposing additional pressures that lead to inequality.

Sharing Networks and Collaborative Practices in the Workplace

The 2008 global financial crisis has encouraged the development of a multitude of self-organized networks and co-produced initiatives where communities of citizens have been trying to address their needs collectively by sharing knowledge, goods, and services (Selloni, 2017). The proliferation of new social and political arrangements that span alternative forms of participatory democracy to alternative markets based on reciprocity are difficult to classify. Still, as pointed out by Vlachokyriakos and colleagues (2017), a number of values distinguish these new arrangements from the traditional economy. Namely, the new market networks focus on cooperation vs. competition, reciprocity vs. isolation, horizontal participation vs. centralized control, and pluralism vs. monoculture.

Sharing economics has also made its impact in the workplace. A form of sharing practice that has become increasingly popular is coworking (Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018) which is characterized not only by the sharing of office spaces and facilities, but also by connecting and sharing social resources, supporting knowledge, and idea exchanges. The integration of sharing practices in the provisions of welfare services is an attempt to provide multiple answers to the problems of traditional welfare by leveraging collaborative practices, co-production, and the use of digital platforms (Morgan & Zeffane, 2003; Pestoff, 2012; Schiavo et al., 2019).

Values and challenges of childcare in the workplace

Work-life balance is an important issue for modern organizations because it mediates several outcomes, including job and life satisfaction (Baral & Bhargava, 2010; Anafarta, 2011; Haar et al., 2014). Traditionally, several welfare policies have been developed to provide a balance between work and private life, based on the assumption that work and life outside of work are separated, as well as that people should have them in balanced proportions (Grzywacz & Carlson, 2007). Recently, a different approach has been proposed, in which work and nonwork life boundaries are integrated together in such a way that welfare policies should support the integration of multiple life roles, and thus the integration of work and personal life (Sirgy & Lee, 2016).

The shift from “work-life balance” to “work-life blending” has influenced welfare policies targeting childcare provision, moving from traditional childcare services (for example, assisting with access to external childcare facilities) to more innovative solutions that emphasize the co-participation of employees themselves. For example, Patagonia, an American company marketing outdoor clothing, was one of the first companies to promote innovative on-site childcare, integrating a pedagogical approach inspired by the company’s values of unstructured play and exploration (Chouinard & Ridgeway, 2016). Connelly and colleagues (2004) discussed how employees working in organizations that provide on-site childcare feel more productive and are more satisfied with their job, they are more likely to return to work after the birth of their child, feel more involved in their child’s daily activities, and have a higher level of commitment to the company. From a company’s perspective, employee-based childcare can promote improvements in worker productivity, as well as reductions in absenteeism, turnover, and recruitment costs, thus benefitting the company towards maintaining a competitive position in the industry. However, on-site childcare facilities require a considerable investment and recurring costs, and, for many companies, the costs may still outweigh the benefits.

On the other side, studies (among others, Rothausen, 1998; Perrigino et al., 2018) have investigated the so-called work-family backlash. This features negative emotions, attitudes, and behaviours associated with work-life balance policies, including on-site childcare provisions. Positive and negative effects of work-life balance policies are mediated by the type of job (Perrigino et al., 2018; Kossek & Lautsch, 2018).

In this study, we contribute to knowledge about the acceptance and adoption of work-life balance initiatives by presenting a case study of two initiatives that, beyond just providing support for childcare, tried to involve employees as co-producers of the service. We analysed the values and challenges of these activities as seen from the perspective of both management and employees, and investigated the support provided by digital technology to facilitate the provision and the acceptance of these initiatives.

A Case Study of Two Initiatives

The case study was conducted within a medium-size knowledge-based organization with almost 400 employees based in North Italy, in the autonomous Province of Trento. The organization holds a Family Audit certification that qualifies an organization’s commitment to a favourable work-life balance of its employees. The certification requires that organizations and companies identify solutions to help improve work-life balance through direct involvement of their employees.

Within this framework, the organization already had experience in the provision of work-life balance initiatives and, to some extent, also the employees were actively involved in some of the implemented activities. For example, summer camps were regularly held in the organization’s premises in which employees’ children could spend the day in educational and entertaining activities, while their parents were at work. During these activities, employees are encouraged to organize and conduct some of these activities with children. Their participation is informally valued while there is no compensation for these tasks, but the time spent is considered as part of their working time. From the point of view of the HR Department, these cross-generational initiatives and the participation of employees were considered as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility plan.

Background and Organization of the Study

The study is organized as an action research intervention in which the researchers both actively participated in the study, while also observing in a participatory way its effects (Stringer, 2013; Coghlan 2019). We framed our study following the Grounded Design approach (Rohde et al. 2017; Wulf et al., 2018) as a case study to understand the design and appropriation of a specific form of service in support of work-life balance, using a digital tool in support of it.

In 2018, one of the research groups in the organization had been involved in a European project called Families_Share (

https://families-share.eu) with the goal of co-designing services and supporting a digital platform for facilitating collaborative childcare initiatives in the workplace. In accordance with the HR department, a decision was taken to create a living lab (Dell’Era & Landoni, 2014). As a first step, institutional stakeholders and employees were involved in order to better understand their attitude toward collaborative forms of childcare. This preliminary study reported by Leonardi and colleagues (2019) identified perceived values and potential barriers of social and organizational arrangements, describing the mediating role of interpersonal trust, social exchange, and reciprocity. The second phase of the investigation consisted in action research inside the organization, as described in this paper below.

The digital tool

One of the outcomes of the first step of the project was to (co-)design and develop an app to support managing the parent groups and decision-making process related to the design and implementation of activities (time schedule, role assignment, registration of children, and so on). The application includes features for building a community around childcare activities, and for supporting the cooperative management of these activities. In particular, the app functionalities available are: i) group creation, ii) membership management, iii) activities creation, iv) management of shifts among volunteers, v) information about children attending the activities (age, special needs).

The action research

As the second step of the case study, two different forms of collaborative on-site childcare initiatives were activated within the organization in close collaboration with the HR department. One (Summer Labs) was based on a mixed collaboration between external professionals (paid by the organization) and the involvement of employees for proposing scientific activities or supporting more mundane activities such as serving food. The other types of activity (the Afternoon Labs) were fully organized and self-managed by the employees, while the organization gave support in term of working spaces and time flexibility. The two activities differed also on the governance approach adopted: Summer Labs were characterized by a prevalent top-down approach from the organization’s management to the employees, while the Afternoon Labs adopted a bottom-up, grassroots collaborative governance involving employees and management.

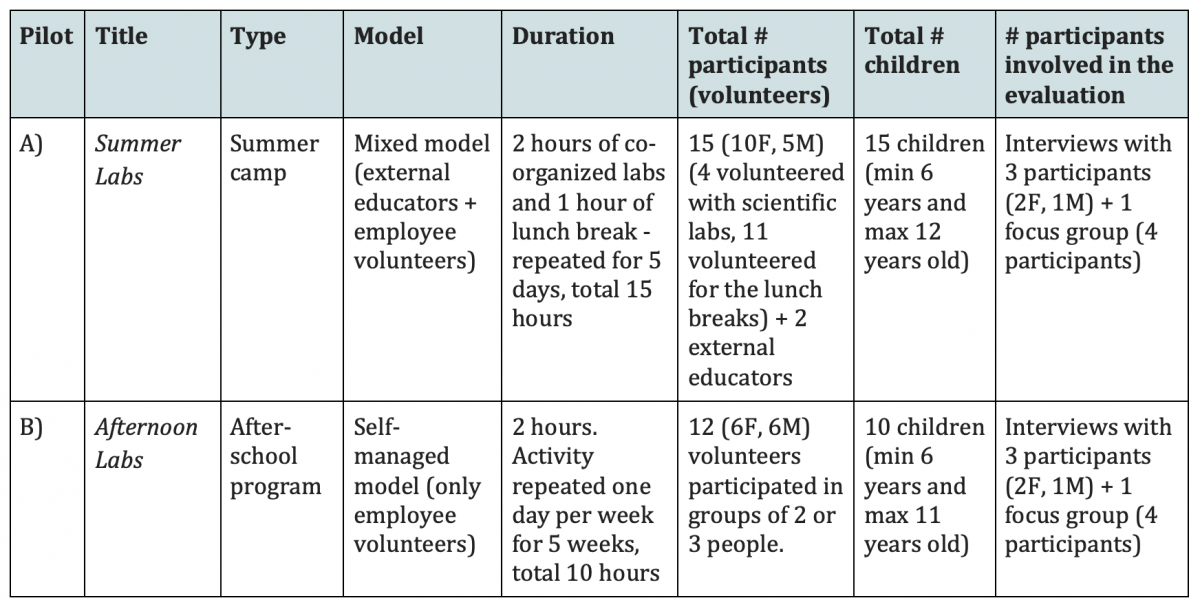

Table 1. Main characteristics of the two collaborative childcare activities investigated in the case study.

Specifically, the characteristics of the two initiatives are summarized in Table 1 and described as follows:

A. Summer Labs: one-week long educational and recreational activities organized for employees’ children during the summer school break. They were run by external childcare professionals with the involvement of employees. Four employees participated as volunteers proposing educational activities, in some cases based on their professional competencies (for example, educational robotics), and in other cases based on other skills (for example, origami). Another 11 employees were involved in more mundane activities, such as providing support during lunch breaks. Volunteering was not set as mandatory for enrolling kids. The organization provided the physical space and covered the costs for the insurance and the external educators. The employees’ participation and coordination were managed by exploiting a digital platform and encouraged by a community management team.

B. Afternoon Labs: after-school activities hosted in a specific dedicated room at the organization’s premises and during the working hours of Friday afternoon. These activities were entirely organized and coordinated by employee volunteers without the support of external childcare professionals (but with the support of the community management team). Each activity was managed by groups of two or three employees. Ten children registered in the activity and participated in the 4 Afternoon Labs. Participation was considered part of working time and the organization provided the physical space and paid the costs for insurance coverage.

Figure 1. Photos from childcare activities described in the case study.

Evaluation: Methods and participants

The evaluation activities consisted of 6 in-depth individual interviews and 2 focus groups (with 4 participants each; different employees participated in the interviews or in the focus groups - see Table 1). In total, 14 employees (knowledge workers, aged 40-50, 6 males and 8 females) were involved on a voluntary basis. All of them participated in the activities of either the Summer Labs, the Afternoon Labs, or both. Thirteen were parents of children participating in these activities, whereas 1 of them volunteered without having any children taking part in the activities.

The 6 semi-structured in-depth interviews explore dimensions related to the childcare experience, including overall evaluation, benefits and criticalities observed, impact on personal work/life balance, and individual consideration of the sharing experience. In parallel, we ran two focus groups (one for each childcare initiative) investigating opinions related to the activities, how the tasks were shared among the group, which challenges they faced and their use of the digital platform. The interviews investigated more personal aspects of co-participation in childcare experience, while focus groups explored social dimensions and group dynamics around such participatory practices. Furthermore, the qualitative data include notes taken by researchers during the observations and discussions carried out with two HR staff members assigned to the project.

Results

The themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis were divided according to the two main perspectives: the point of view of employees, and the point of view of the organization.

Employee perspectives

Wellbeing and work-life integration

These activities had a positive impact for all participants on their personal wellbeing, helped improve the quality of the organizational context, and contributed to the development of a more inclusive workplace. Participants remarked that these activities represent a good opportunity to manage work-life balance. Yet, the positive impact was considered more for employees living close to the organization’s premise. For those living further away, the effort of commuting may reduce some of the perceived benefits. For most parents, the childcare initiatives were very convenient when matching their work schedule (for example, summertime or other vacation periods, unexpected closures such as in case of strikes). Another aspect that emerged as important was the positive value of organizational wellbeing (Cartwright & Cooper, 2009). For example, participants reported that a more blurred division between personal and professional life may break down the strict division of work and life and create a more inclusive and positive working environment. Another example was the increased sense of community reported by the participants: new relationships are built with colleagues. Shared childcare experiences in the workplace foster trust and a sense of reciprocity. Nevertheless, some participants noted that these effects might also be a barrier to access workplace childcare services, since some employees may prefer to keep work and life separated. These employees might be willing to use a standard childcare service organized in the workplace, but might refrain from participating in such sharing activity if they feel the pressure to actively participate as volunteers too.

Parent involvement

The participation of parent employees in the delivery of care on-site has been in general positively valued. As already remarked by employees during the co-design activities (Leonardi et al., 2019), a strong value of on-site childcare is that children can participate more actively in their parent’s daily routine and can have the opportunity to get familiar with their parent’s workplace and professional life. In this sense, collaborative childcare activities allow parents to spend more time with their children, especially during the school breaks, and to be more involved in their lives. The motivations of participating parents were related to their willingness to share their professional competences, such as their area of expertise or their research topic, translating their knowledge into something that their children can also understand and appreciate. Yet, preparing for and carrying out labs is both demanding and difficult in the task of identifying activities suitable for groups of children of different ages. This aspect convinced several parents to volunteer for more mundane support activities as needed (like helping during lunch time), rather than proposing to lead or assist with educational activities.

Recognition of participation

Some volunteering parents felt that their participation was not properly recognised by the organization, at least not in a formal manner. Although participation was indeed taking place within working hours and employees were authorized by management, the participants suggested that this aspect should be formalized in the organization’s internal regulation. For example, employees may have a certain number of hours allocated for community volunteering activities, which can be proposed as internal on-site activities that promote work-life balance, along with other external activities.

The limits of participation

Although the co-production of childcare services in the workplace was considered an intriguing idea, completely self-organized childcare activities by the employees have been thought appropriate only for shorter stay childcare activities, involving a limited number of children (5 to 10) for more limited amounts of time (few hours or an afternoon, as in the study). Several participants noted that in case of week-long activities like a summer camp, the presence of external educators is much needed. This was motivated by the higher effort required to plan and manage week-long activities, and by the lack of skills required by participants to manage large groups of children, possibly including children with behavioural/emotional difficulties, for long periods of time. In this respect, the presence of professional educators during the week-long Summer Lab was considered important such that the participating employees regarded their participation as a significant opportunity for personal growth.

Managing conflicts among children is considered as a sensitive issue in particular because it takes place in the working environment where volunteering parents are also colleagues. This means that power relations and hierarchies are in some ways implicitly in place even during these kinds of activities.

Nevertheless, participants did not suggest completely removing the role of employees’ participation. Synergy between the professional educators and the volunteering employees was thought to enrich the educational value of the experience for the children. This means professional educators can support employee volunteers in the ideation and implementation of educational activities. As these will be partly based on the particular skills of employees at the organization, it may provide a unique opportunity for children and a valuable way to connect with their parents. On the other side, professional educators can equally benefit from the support of workplace volunteers for managing their regular activities, such as lunch breaks or outdoor activities, thereby reducing the cost of on-site service.

The role of technology

Overall, 11 participating employees (41% of the total) downloaded the app and actively used it for managing activities during the childcare initiatives. The app was regarded to be more useful for self-organized activities, rather than for supporting activities that involved the presence of professional educators. For the Summer Labs, several actors worked together in the process of organizing activities in various roles (the HR department, the social cooperative of educators, as well as many employees, both parents and volunteers).

Furthermore, the needed planning activities were more and more complex (requiring organization of lunches, activities spanning several days, issues related to insurance and so on). Because of this complexity and the physical proximity of the actors involved, face-to-face meetings were easier and more effective. Nevertheless, the app proved useful for impromptu planning and coordination of small tasks among the volunteers, such as coordinating the schedule of educational activities, or the lunch duty shifts. For these cases, face-to-face meetings would have been time consuming and inefficient, while having a mobile channel able to support last minute scheduling was valued positively.

In line with findings described in Leonardi (2019), we witnessed employees' concerns about the introduction of technology. They criticized the idea of having to use another social media and expressed concerns of “bureaucratizing” the participation process with a tool that requires users to follow predefined procedures. One of the added values for employees to participate in childcare activities was felt to be the informal interaction with colleagues, and the opportunity to relate to the organization’s management in a friendlier way. Employees also appreciated the opportunities offered by the app of efficiently organizing shifts among colleagues in a way that could be quickly updated for any changes to the schedule of activities.

Organizational perspectives

Collaborative childcare has been identified by HR departments, as well as by organizational governance as an opportunity that matches the interest of organizations toward work-life balance initiatives, the increase of employee participation in welfare initiatives (“participative welfare”), and the strengthening of employees informal social networks (workplace as a “community of people”). These positive aspects emerged in the case study as discussed above. Nevertheless, along aspects that can be considered as enablers for the adoption of collaborative childcare, several potential barriers also emerged from our study.

Logistic issues

One problematic aspect that often surfaced in discussions with HR representatives regarded the budget. Although the initiative’s cost may be reduced by employees participating as volunteers, and even more in the case of totally self-organized activities, these types of initiatives are anyway more expensive than the typical work-life benefits offered by companies. This is the case in particular if the time of HR staff and working hours of volunteering employees are properly accounted. Another potential barrier concerns the types of duties of the employees. For instance, collaborative childcare services might be more difficult to attend by staff with working shifts, or by employees in front-end service positions with customers. This may prevent the possibility of organizing workplace childcare with such modalities, or it may provide only the reality of unfair access to it inside an organization.

Legal and insurance aspects

Insurance and legal aspects are critical, specifically because young children are involved. Beyond simple budget issues, the possibility of negotiating insurance coverage for children in a workplace is not simple. It requires the need of properly equipped spaces and access to proper infrastructure that are not always available in a workplace context. It also needs an assumption of responsibility by the management team. From the legal point of view, it requires dealing with family privacy issues to an extent than an organization or its employees might be ready.

The role of technology

From the point of view of the organization, the app, which was designed specifically to support employees’ collaboration, received ambivalent responses. From one side, it was considered useful, at least in principle, by alleviation their supervision effort on employees’ collaboration, and as a tool that might encourage employee engagement. As discussed above, the additional effort needed by HR staff to manage this service for work-life balance emerged as a major concern. The app may thus also serve as a tool for monitoring activities as well as to effectively communicate norms and regulations. From the other side, the use of the app by the HR representative was very limited and mediated largely just by the researcher involved in the study.

Communication challenges

Another barrier was the difficulties in efficiently communicating opportunities to employees and quickly assessing their needs in terms of work-life balance. This represented a main critical feature for employee engagement, and for a proper mapping of employees needs. The making of a map can turn in a mismatch between employee needs and what the organization offers. For instance, the organization examined in this case study uses an online survey to map the needs of parents in terms of childcare. But there is often a mismatch between the collective needs and the participation of employees to initiatives proposed by the organization aimed at addressing those needs.

Conclusion

Our case study was based on the implementation and analysis of two different initiatives of collaborative childcare in the workplace. This was part of a wider program of work-life balance pursued by the organizations and encouraged by local administration policies. The two childcare initiatives differed on the duration and degree of involvement of employees, and on a combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches. Both situations provided an opportunity for employees to experience support for a better blending of work and family life, by being involved in a community of co-working parents and actively participating in childcare activities. As already discussed in the literature (Connelly et al., 2004), this experience tends to have a strong positive value for all the employees, not only the ones involved in the initiatives.

Despite initial enthusiasm for the program, the study highlighted some problematic aspects too. Participation might be too demanding in terms of time, effort, and emotional involvement for the employees. Sharing practices require active and cohesive communities of peers in order to create and coordinate sharing initiatives (Vlachokyriakos et al., 2017). At work, these networks include colleagues and are characterized by heterogeneity of relationships and potential conflicts between them (Berman, 2002). For organizations too, despite the reduction of external costs, it requires much effort in terms of dealing with logistic and legal aspects. Completely self-managed activities might be too demanding to be sustained for long periods and require a community of highly motivated employees, who are willing to commit to multiple cohorts of young children. A mixed model that balances the support of external professional competences in childcare with a limited involvement in terms of on-site support and involvement in educational activities by employees seems to maximise the benefits and minimize the drawbacks.

Our study confirms that collaborative childcare can be an effective way to implement work-life balance services. Offering it also provides an opportunity to improve other aspects of organizational wellbeing, such as a greater sense of community. Nevertheless, the cost and effort to sustain such practices should not be under-estimated. There is a need to provide adequate activity space and comply with specific regulations for the presence of children in an organization’s premises, as well as to negotiate insurance and assume specific responsibilities among employees. Furthermore, it is worth noting, that together with an increase in organizational wellbeing, this approach raised the request for a more formal and structural way of recognizing employees’ participation, together with a request for wider recognition for the value of volunteering by employees.

Regarding the role that digital technology might play, our study provided evidence of the need to support this form of collaborative practice, while its actual use was hindered by the possibility of face-to-face meetings, and previous negative experiences with other digital tools for office productivity. Nevertheless, the app was used and considered useful for planning and executing small and simple tasks on a schedule. This may provide some initial evidence that a transition to the app may happen in the longer term, overriding a negative “familiarity effect” coming from other tools, which prevented the app’s full use by employees in this study. A different aspect concerns the (lack of) use of the app by HR staff. While the app was considered useful to monitor and regulate self-organized activities by employee-volunteers, it was not designed in a way to facilitate integration with the organization’s existing IT infrastructure.

Lastly, considering government innovation and the role of public authorities, public bodies devote significant efforts at making childcare more available. Companies, as well as labour unions and civil society groups, are and should be central to this effort. While there is still considerable progress to be made, the active involvement of both public and private sectors, as well as a more direct involvement of parents/employees in the management of childcare activities can be considered as a promising approach for improving and extending childcare services. In this respect, the creation of innovative and flexible childcare arrangements based on public–private partnerships, such as the ones presented in this study, might show how to leverage resources from peer support and highlight the value of collaborative networks to harness and share efforts to provide workplace childcare.

In conclusion, the experience and results reported in this case study contribute to the ongoing debate on collaborative practices in the workplace. They provide informed suggestions on how to handle infrastructure top-down and bottom-up approaches in a way that creates a socio-technical environment for shared childcare in the workplace. This work investigates how childcare services can be reimagined thanks to the synergy between local authorities’ programs, the endorsement of companies and organizations, and the direct participation of voluntary employees. Perceived values and potential barriers of social and organizational arrangements around such innovative caring practices were presented, in the hope that these insights can guide companies and practitioners in further unveiling the potential of collaborative and shared practices in the workplace. The results reported in this case study are also relevant to government and public authorities as examples with insights for implementing innovative forms of childcare solutions based on public-private partnerships and collaborative engagement for greater work-life balance.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in the paper was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement N° 780783 (FAMILIES_SHARE).

Anafarta, N. 2011. The relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(4): 168-177.

Baral, R., & Bhargava, S. 2010. Work‐family enrichment as a mediator between organizational interventions for work‐life balance and job outcomes.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(3): 274-300.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011023749Barcevičius, E., Cibaitė, G., Codagnone, C., Gineikytė, V., Klimavičiūtė, L., Liva, G., & Vanini, I. 2019. Exploring Digital Government transformation in the EU. doi:10.2760/17207, JRC118857.

Berman, E.M., West, J.P., & Richter, Jr, M.N. 2002. Workplace relations: Friendship patterns and consequences (according to managers). Public Administration Review, 62(2): 217-230.

Brandsen, T., Verschuere B., & Steen, T. (Eds). 2018. Co-production and co-creation: Engaging citizens in public services. Routledge.

Bouncken, R.B., & Reuschl, A.J. 2018. Coworking-spaces: how a phenomenon of the sharing economy builds a novel trend for the workplace and for entrepreneurship. Review of Managerial Science, 12(1): 317-334.

Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C.L. (Eds.). 2009. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-Being. OUP UK.

Chouinard, M., & Ridgeway, J. 2016. Family Business: Innovative On-Site Child Care Since 1983. Patagonia.

Coghlan, David. 2019. Doing action research in your own organization. SAGE Publications Limited.

Correia de Sousa, M., & van Dierendonck, D. 2010. Knowledge workers, servant leadership and the search for meaning in knowledge‐driven organizations.

On the Horizon, 18(3): 230-239.

https://doi.org/10.1108/10748121011072681Dell'Era, C., & Landoni, P. 2014. Living Lab: A methodology between user‐centred design and participatory design. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2): 137-154.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Carlson, D. S. 2007. Conceptualizing Work—Family Balance: Implications for Practice and Research.

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 9(4): 455-471.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422307305487Grosser, K., & Moon, J. 2008. Developments in company reporting on workplace gender equality?: A corporate social responsibility perspective.

Accounting Forum, 32(3): 179-198.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2008.01.004Haar, J.M., Russo, M., Suñe, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. 2014. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3): 361-373.

Hein, C., & Cassirer, N. 2010. Workplace Solutions for Childcare. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

Kossek, E.E., & Lautsch, B.A. 2018. Work–life flexibility for whom? Occupational status and work–life inequality in upper, middle, and lower level jobs. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1): 5-36.

Lewis, J. (Ed.). 2018. Gender, social care and welfare state restructuring in Europe. Routledge.

Leonardi, C., Schiavo, G., & Zancanaro, M. 2019. Sharing the Office, Sharing the Care? Designing for Digitally-mediated Collaborative Childcare in the Workplace. In Proceedings of Communities and Technologies C&T 2019.

Morgan, D., & Zeffane, R. 2003. Employee involvement, organizational change and trust in management. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(1): 55-75.

Osborne, S.P., Radnor, Z., & Nasi, G. 2013. A new theory for public service management? Toward a (public) service-dominant approach. The American Review of Public Administration, 43(2): 135-158.

Pestoff, V. 2012. Co-production and Third Sector Social Services in Europe: Some Concepts and Evidence.

VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(4): 1102-1118.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9308-7Rohde, M., Brödner, P., Stevens, G., Betz, M., & Wulf, V. 2017. Grounded Design—A praxeological IS research perspective.

Journal of Information Technology, 32(2): 163-179.

https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2016.5Rothausen, T.J., Gonzalez, J.A., Clarke, N.E., & O'Dell, L.L. 1998. Family‐friendly backlash–fact or fiction? The case of organizations on‐site child care centers. Personnel Psychology, 51(3): 685-706.

Schiavo, G., Villafiorita, A., & Zancanaro, M. 2019. (Non‐) Participation in deliberation at work: a case study of online participative decision‐making. New Technology, Work and Employment, 34(1): 37-58.

Selloni, D. 2017. New forms of economies: sharing economy, collaborative consumption, peer-to-peer economy. In CoDesign for Public-Interest Services, Springer: 15-26.

Stringer, E.T. 2013. Action Research. SAGE Publications Limited.

Vlachokyriakos, V., Crivellaro, C., Wright, P., Karamagioli, E., Staiou, E.R., Gouscos, D., Thorpe, R., Krüger, A., Schöning, J., Jones, M. & Lawson, S. 2017. HCI, solidarity movements and the solidarity economy. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 3126-3137.

Wang, H., Tong, L., Takeuchi, R., & George, G. 2016. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview and New Research Directions.

Academy of Management Journal, 59(2): 534-544.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.5001Wulf, V. (Ed.). (2018). Socio-Informatics: A practice-based perspective on the design and use of IT artifacts. Oxford University Press.