AbstractIt's how you deal with failure that determines how you achieve success.

David Feherty

Professional golfer

This study examines the failed internationalization experience of a Brazilian high-tech startup. The research methodology of the study is descriptive and aims to explore whether this startup should re-internationalize, despite an unsuccessful first experience. Based on interviews with the founders, it was found that the initial internationalization took place in an incipient way, in the heat of the moment. The lack of success with the initial internationalization did not shake the directors of the startup, who aim to return to internationalization, now in a consolidated way and counting on the advice of an investor. Despite its bitter first experience, should the startup try again? Through an analysis of the lessons learned from the startup’s initial failure and insights from its consideration of a possible second attempt, this study contributes to the literature on competitiveness, internationalization, and international entrepreneurship.

Introduction

Technology-based startups have been growing exponentially in Brazil (ABStartups, 2018). Faced with a limited market with global potential, a technology startup aims to internationalize early and fast. These high-tech companies provide innovative products and services and operate as pioneers in a small global niche market (Neubert, 2015).

A company born of a small, open economy is often forced to internationalize early and fast to become profitable (Neubert, 2016a). However, early and rapid internationalization is very challenging for entrepreneurs because it requires specific skills and excellent preparation, including, for example, product adaptations (Neubert, 2016b).

This study stems from the authors' research on the themes of entrepreneurship and internationalization, and it focuses on the Brazilian scenario regarding the exponential growth of startups and the need for global technology startups to grow beyond national boundaries. The startup under study unsuccessfully attempted to internationalize shortly after its foundation. For the founders, it was a bitter result. However, years later, with the experience they have acquired and the injection of investment, the founders are considering a second attempt. To internationalize or not to internationalize? That is the question that is again facing the founders, and that is the focus of the present study.

In order to answer this question, the initial experience with the failed internationalization, the current startup context, the economic scenario, and the justification for potential expansion are described in this article. First, we review the literature on internationalization, export barriers, the origin and concept of startups, and related areas. Next, we summarize our descriptive research methodology. Then, we describe the results and discuss the history and current situation of the case. Finally, we conclude the article with a list of key findings and recommendations.

Literature Review

Internationalization

As the globalization of markets progressively develops, our understanding of cultural and social aspects emerges as a fundamental challenge in the process of internationalization of companies, in the search for global markets, and in the attraction and mainly maintenance of these new consumers (Honorato, 2007). Therefore, internationalization, according to Fleury and Fleury (2012) can be defined as a phenomenon that is related to the social actors that participate in the process of globalization, which they are public or private companies, or governmental or non-governmental institutions. Thus, internationalization is considered as the largest dimension of the continuous process of strategy and can be defined as a process involving a company in its operations with other countries (Melin, 1992; Reid, 1981). In this sense, companies can broaden the scope of their operations by insertion in international markets offering multiple products to different nations (De Moraes et al., 2015).

In this way, internationalization allows a company to become more competitive inside and outside its home country (Da Silva et al., 2016). In the process of internationalization, changes in coordination mechanisms associated with institutions and the market end up reflecting cultural exchanges and power disputes between nations and organizations (Lopes et al., 2007). However, for companies that want to expand their products or services to international markets, it becomes essential to gain legitimacy in foreign markets (Da Rocha et al., 2015).

Regarding the classification of internationalization theories, Carneiro and Dib (2007) address two main lines of research: the internationalization approaches based on economic criteria and the internationalization approaches based on behavioural evolution. According to the authors, the economic approach favours rational (pseudo-) solutions to questions arising from the internationalization process that would be oriented toward a decision-making path that would maximize economic returns. The second approach, based on behavioural evolution, assumes that the process of internationalization depends on the attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour of the decision makers, who would be guided by the search for risk reduction in decisions about where and how to expand.

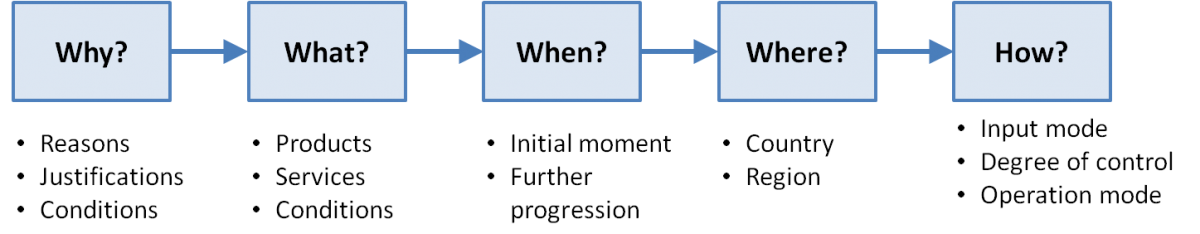

According to Carneiro and Dib (2007), the internationalization process progressively answers six basic questions, as shown in Figure 1 and elaborated in Table 1 according to the theories that help firms find answers to these questions. In the present study, the Uppsala internationalization process model was used, considering that the Uppsala School studies internationalization from a behavioural perspective in which the process of internationalization would depend on the attitudes, perceptions, and behaviour of decision makers, who would be guided by the search for risk reduction in decisions on where and how to expand (Carneiro & Dib, 2007).

Figure 1. Basic questions addressed during the internationalization process (Adapted from Carneiro & Dib, 2007)

Table 1. Answers to the basic questions of the internationalization process according to the Uppsala stages model (Adapted from Carneiro & Dib, 2007)

|

The Uppsala Stages Model |

|

|

Why? |

Market research. |

|

What? |

No restrictions in terms of products, services, technologies, or activities (implicit). |

|

When? |

Initial moment: saturation of the domestic market. Expansion: as knowledge is gradually gained through international experience. |

|

Where? |

For countries with "psychic distance" relative to the smaller domestic market at first, and then gradually increasing. |

|

How? |

In stages of gradual commitment of resources (first export, then sales office until production in the new market). |

Uppsala internationalization process model

Developed by the researchers Johanson and Vahlne in 1977, the Uppsala internationalization process model tries to explain the characteristics of the internationalization process of the firm, assuming a dynamic learning process of the firm (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Thus, internationalization ends up being a result of the relationship of the development of learning, the acquisition of experience, and the commitment of resources (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977).

In addition, internationalization begins in the domestic market and the emergence of new opportunities allows the firm to make new investments in the foreign market (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Rezende (1999) points out that the internationalization process involves learning and successive acquisition of skills to enter the new market. This process occurs in three stages: obtaining information about the country of destination, choosing the product, and choosing a form of entry (Rezende, 1999).

Thus, the internationalization process occurs in a gradual manner and with the growth of information regarding the market to be exploited. This information can be derived through the company's own experience and through research and reports, thus increasing the company's abilities to identify the opportunities and threats of the market, thus establishing strategies for action (Johanson & Vahlne, 1993).

Export barriers

Increasingly, recurrent and essential export practice among countries contributes to capital movements and economic development, given that the world economy functions in an integrated manner and national economies are interconnected. The growth of the world economy depends on the trade between the countries, and the main way for the growth of the economies ends up being the expansion of international trade.

International trade has been playing an increasingly important role in the world economic scenario. In this sense, the liberalization of trade in goods and services, mainly through the dismantling of the barriers imposed on the frontiers of trade between countries, is necessary (Thorstensen, 1998). However, according to Mazon, Jaeger, and Kato (2010), companies venturing into international trade find themselves facing new barriers or at least barriers that are different from those of their domestic market. In this context, Leonidou (1995) states that export barriers are the reason for many failures in the international market, leading to financial losses together with a negative perception of companies in international trade.

In addition, Leonidou (2004) states that the concept of export barriers encompasses all the restrictions that hinder the ability of the company to initiate, develop, or preserve business operations in foreign markets. Machado and Scorsatto (2005) cite that companies whose executives perceive high barriers are less likely to export or, if they did, would remain at preliminary levels of export activity. Leonidou (1995) argues that export barriers can be divided into two main groups: internal and external. According to that author, the internal barriers are those related to the organizational resources and with the capacity and approach that the company possesses with regard to the export business. On the other hand, external barriers, according to Leonidou (1995), are associated with the obstacles that the company faces in its country of origin and the host country in which it operates.

Internal barriers can be subdivided into functional, informative and marketing barriers (Leonidou, 2004). The functional barrier refers to the inefficiencies of the various business functions, such as human resources, production, and finances when it comes to exports (Vozikis & Mescon, 1985). An information barrier, on the other hand, refers to problems in the identification, selection, and contact with the international market due to inefficiency of information (Morgan & Katsikeas, 1997). The marketing barrier essentially extends to product, price, distribution, logistics, and dissemination of the company's activities in the international market (Moini, 1997).

Leonidou (2004) divides external barriers into four sub-items: procedural, governmental, task, and environmental barriers. The procedural barrier highlights the operational aspects regarding the transaction with foreign clients (Kedia & Chhokar, 1986). Government participation and encouragement in the choice of appropriate trade policies for export promotion is necessary. In this sense, Leonidou (2004) affirms that government barriers allude to action or omission by the government of the country of origin. In addition, Leonidou emphasizes two issues pertaining to government influence on export: limited government interest in assisting and encouraging potential exporters and the restrictive role of the regulatory framework in export practices.

According to Uner and colleagues (2013), economically emerging countries have demonstrated major regulatory, regulatory, and incentive barriers that act as a stumbling block to internationalization. Leonidou (2004) points out a third sub-item related to external export: the service barrier. The divergence of habits and attitudes in the various countries around the world is prominent. In this sense, Leonidou (2004) defines it as being related to the company's customers and external market competitors and the effect they exert on export operations.

Environmental barriers include several obstacles, mainly economic and financial. Leonidou (2004) places special emphasis on the following topics: economically deprived foreign markets, foreign exchange risks, political instability and strict regulations in the foreign country, high tariff and non-tariff barriers, foreign business practices, socio-cultural characteristics, and different verbal language of the country of origin.

In alignment with the above, Oviatt and McDougall (1994) reiterate that a company in conducting transactions in a foreign country faces some disadvantages compared to local companies, among them governmental, legal, language barriers and in business practice. However, when properly conducted, cultural differences can lead to innovative practices within the organization and become a competitive advantage (Cox & Blake, 1991).

Startups

Not long ago, “a startup” was synonymous with a small business in its initial stage (Gitahy, 2010). The concept has evolved and, today, experts, investors, and entrepreneurs adopt the idea that startup is basically an enterprise that faces an environment of extreme uncertainty, that is, it is a group of people seeking to undertake business in markets where little is known about key variables. Startups are early-stage organizations focused on a scalable business model (Antonenko et al., 2014). As a source of innovation, a startup uses emerging technologies to invent products and reinvent business models (Kohler, 2016); it is an institution “designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty” (Ries, 2011).

This definition says nothing about the size of the company, so it may be assumed that anyone who is involved in creating a product or service where great uncertainty prevails is involved in a startup. Another important consequence of the definition is that innovation is implied as a key component. It is not about creating something revolutionary, even though it can happen, but at least the activity seeks to bring a new source of value to customers, either by providing a solution in a previously overlooked market or by making use of existing technology. Also, we highlight the fact that startups deal with extremely uncertain environments, with little information, and where it is often not clear who the customer is (Ries, 2011).

As a final note, consider how recently the startup concept became commonplace, especially in Brazil. According to Gitahy (2010), the concept of a "startup" in entrepreneurship gained popularity in the United States starting in 1990, in step with the emergence of the “Internet bubble”. However, it was only in the period from 1999 to 2001 that the term began to be diffused in Brazil.

Research Methodology

The approach used in this research is qualitative and descriptive. The definition of qualitative research for Yin (2015) considers five characteristics: i) study the meaning of the real life of individuals; ii) represent opinions and perspectives of individuals in a study; iii) encompass the contextual conditions in which individuals live; iv) contribute with revelations about existing or emerging concepts that can help explain human behaviour; and v) strive to use multiple sources of evidence instead of relying on a single source. In this sense, qualitative research subjects should be individuals or groups that are involved in similar experiences (Creswell, 2014).

For Sampieri, Collado, and Lucio (2013), the qualitative approach is used when trying to understand the perspective of individuals about the phenomena that surround them, under their experiences, points of view, opinions, that is, how participants subjectively perceive their reality. For Antonello and Godoy (2011), this technique gains prominence among the various existing techniques, due to the subjective context of the individual, based on experiences, based on their feelings, beliefs, ideals, and propositions.

Descriptive research seeks to describe the characteristics of a particular population or the facts and phenomena of a reality, which may provide a greater familiarity with the problem, making it more explicit and favouring the improvement of ideas and considerations of the most varied aspects linked to the fact studied (Triviños, 1987).

Data collection was done in November 2017 using a semi-structured script for interviews with the founding directors of the startup being researched. It was composed of open questions in which the interviewee had the opportunity to discuss the proposed topic without answers or conditions prefixed by the researcher (Minayo, 2012), and it was guided by basic questions about the proposed theme (Triviños, 1987). The semi-structured interviews started with broad questions, so that the interviewee felt free to talk; in addition, the researcher–interviewer did not interrupt the interviewees. The interviews were deep, with an average duration of one hour and occurred in in places of preference of the interviewee. Interviews were only carried out with the consent of the interviewee, a previous appointment was made with each one, in which the objective of the research was presented, at which time a commitment was established between the two parties: interviewer and interviewee.

The choice of interview technique is based on Belk, Fischer, and Kozinets (2013), who suggest that the interview has become popular as a way of collecting qualitative data in research on behaviour in the applied social sciences, whether it is considered open, in-depth, or semi-structured. Triviños (1987) states that the semi-structured interview “favors not only the description of social phenomena but also their explanation and understanding of their totality”.

The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and subsequently analyzed using the technique of content analysis, which comprises a set of communication analysis techniques aiming to obtain – by systematic procedures and objectives of description of speech content – indicators that allow the inference of knowledge regarding the conditions of production or reception of these messages (Bardin, 2011). The content analysis was performed with emphasis on categorical analysis and the enunciation. The categorical analysis is structured based on the interviewees' reports, and the categories of analysis are established to represent similarities between the reports of the majority of respondents and similarities between their behavioural characteristics and their perceptions about the phenomenon that is being studied. The enunciation analysis is the process of segmenting the texts of the interviews, already summarized, into smaller units, which can be phrases, sentences, paragraphs and even topics. The analysis of data was structured by the procedures of organization, treatment and analysis of the data collected to understand them, answer the research questions, and generate knowledge (Sampieri et al., 2014).

Results and Discussion

Case overview: Chip Inside

The Guedes brothers, Leonardo (an electrical engineer) and Thiago (a mechanical engineer), were born in the interior of Rio Grande do Sul, in the south of Brazil, and always had the will to undertake challenges. It was within a research group that they participated in a technology transfer project for animal monitoring equipment. The brothers saw that technology had the potential to become a product and decided to start a company, which they named “Chip Inside”.

Chip Inside Technology develops animal-monitoring products for precision livestock management. The startup was created in August 2010 with the objective of developing “innovative high-technology solutions, integrating embedded electronics and software”. The startup’s solutions focus on the stages of design, development, manufacturing, sales, and after-sales support. In 2018, after eight years of operation, the company has a team of more than 30 employees at the technical, undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels. It is considered one of the most promising startups in Brazil’s technological segment.

The company is currently incubated at Pulsar Incubator in partnership with the Agency of Innovation and Technology Transfer (AGITTEC) at the Federal University of Santa Maria in the south of Brazil. In its portfolio, Chip Inside offers two services: C-Tech HealthyCow and CowMed Assistant. C-tech is a collar that enables a farmer to monitor each of their animal’s rumination, activity, temperature, and reproductive parameters. The C-Tech HealthyCow collar is available for purchase or loan.

The client has the option of paying a monthly fee per animal for a “full monitoring package”. This package enables the C-Tech system, which guarantees the operation or replacement of the equipment, including collar batteries, in addition to providing access to CowMed Assistant.

CowMed Assistant is the first remote health care assistance plan for dairy cattle. CowMed Assistant’s team of veterinarians, zootechnicians, and technicians remotely monitor herds and assist farmers with decision making. Through the C-Tech HealthyCow System, the technical team accesses the property data online and exchanges information with its technical staff on a daily basis. CowMed Assistant is not intended to replace the farmer’s expertise or the expertise of their staff, but it provides information that helps in decision making.

The value of the product is in the information, as the brothers Guedes explain:

“Value is information – value is the database of animals. It is this thing to ask the cow which diet is good for her, which remedy works best. The idea is to have a considerable number of cows monitored so that they no longer need to ask, and can tell the farmer in the future which animal will perform better under certain conditions on such a diet and, if it becomes sick, which remedy more indicated. But, this in a while, because we need to have a lot of cows monitored. Information has value for us, much more than the product or the service. When we sell to the producer, I do not have access to that information, so we prefer to earn a little less now, but have the information.”

Today, the startup’s collars monitor approximately two thousand cows. The projection for the year 2018 is ten thousand monitored cows, and for 2021 it is one hundred thousand cows monitored through CowMed Assistant. For the Guedes brothers there is a great potential demand, given that the national dairy herd is 22 million animals, and that is only considering the potential for growth within Brazil. Even greater growth may be realized through internationalization.

In 2017, the startup became the first company selected to obtain resources from the Criatec 3 investment fund. The startup will receive R$2 million (approximately $800,000 CAD) from the fund over five to six years, during which the fund becomes a minority partner of the company, injects money, and participates in decision making. At the end of the participation period, the fund sells its interest either to the majority shareholders or to new investors. From the investment, the next innovation of the startup is to develop a technology related to artificial intelligence, so that robots can monitor the data of the thousands of cows scattered throughout Brazil without interruption. The funding will also be applied to international trade expansion.

To internationalize or not to internationalize?

To answer this question of whether or not the startup should internationalize, we reflect on our discussions with one of the founders of Chip Inside, Leonardo Guedes, who is currently Director of the startup. He shared his previous experience of internationalizing the startup, the option to try again, and future plans for the company. The analysis of the interview is based on Johanson and Vahlne's (1977) theory of internationalization through learning.

Given the uncertainties and imperfections in a new market, Johanson and Vahlne (1977) argue that the internationalization process should occur incrementally. In this way, the companies initially develop in their internal market and the internationalization ends up being a consequence (Monticelli et al., 2017). This pattern matched the Guedes’ experience:

“We serve, for the time being, the southern region of Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Paraná) and intend to expand to other regions of the country (Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso, and Goiás, for example). From next year, [2018] we intend to resume the process of internationalization of our company.”

From internationalization through learning, the process of internationalization is based on the gradual acquisition and use of knowledge in foreign markets. Therefore, companies invest resources and acquire knowledge in a certain foreign market and the commitment increases as knowledge grows (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), as confirmed by the Guedes brothers:

“Our first contact with Uruguay took place in 2015 at a fair in which we were participating [Expointer]. Thus, the idea came to expand our business to Uruguay. We translated all software and graphics into Spanish. We were founding our company at the time and we wanted to enter the Uruguayan market through Selecta [an international dairy products company]. We did not make any sales during the time we stayed in Uruguay. We had insights that came out of this international partnership, but we ended up making no concrete sale.”

Among the difficulties perceived in Uruguay, Guedes mentions:

“We went to the wrong place because we were starting to put the product on the national market – we had no basis abroad. As much as Selecta wanted to represent us there, the system had just been launched in Brazil. It was much more in the heat of the moment – ‘Let's go to Uruguay! Let's internationalize the brand!’ – than an actual plan to go.”

Faced with frustration, the directors chose to withdraw from Uruguay and keep the business only in the national market. In Brazil, failure still carries a stigma (Minello & Scherer, 2014). Over the last few years, the startup has focused on improving the product and expanding in the domestic market.

Currently, the scenario in Brazil regarding milk cattle is unstable due to the high production levels and the low national demand, which results in a low price for the rural producer. In addition, Brazil imports the lowest value product, mainly coming from Uruguay. These factors indicate that perhaps it is time for Chip Inside to internationalize.

As far as the publicity and sale of the products and services the startup participates in fairs. Because it is an innovative product, newspapers and magazines are keen to publish stories about the company, which ends up being a form of free marketing. In addition, the startup emphasizes product quality and better results for its customers. A satisfied customer will talk favourably about the company to other potential customers. This word-of-mouth marketing demonstrates greater credibility with customers, because people do not trust companies, people trust people. Based on this observation, the management decided to work with other companies in the sector, such as Ourofino Saúde Animal and Cargill. Through such partnerships, the sale of products and dissemination of information increases because they are targeted to the right audience.

Conclusions

Faced with an increasingly technological global economy, the risk is the deepening of economic differences between developed and underdeveloped countries. Countries with few resources run the risk of being further marginalized from economic development, created from innovation centres. In this sense, it is important to promote the expansion of technology startups in the most diverse countries, developing and underdeveloped, to reduce this distance.

This study describes the experience of a startup in the face of internationalization and the desire to return to internationalization. The theoretical basis is centred on the Uppsala model, examining failure and learning in the face of internationalization, and the need for a technology startup to become global. In spite of its initial failure with internationalization, this experience served as learning for a greater maturation of the direction of the startup. Years later, also driven by an investor, Chip Inside's management aims to return to the global market, now with its feet on the ground, given the potential of its product and the limitations of the market.

The results of this study contribute to the field of international research on entrepreneurship through a better understanding of how and why technology startups in developing economies, such as Brazil, can act in the face of the desire for internationalization. Of course, success is obviously the preferred outcome, but failure should not carry a stigma; rather, it should be considered an important learning experience. In addition, the results also increase the managerial practice because they will help the directors of other startups who intend to enter the international market.

Although they were unable to serve the Uruguayan market at that time, the internationalization attempt ultimately served as a form of apprenticeship. Among the positive and negative experiences acquired during this process, some stand out. On the positive side, the startup developed its knowledge of the needs of the Uruguayan market, as well as the country’s customs and regulations. On the negative side, the startup found that it was not prepared to enter the Uruguayan market and suffered as a result of an impetuous decision.

The research was limited to studying a Brazilian startup with a focus on its unsuccessful experience of internationalization and its desire to return to internationalization. Future studies may contemplate a larger sample, comparing experiences of internationalization among technology startups in different cultural contexts, including developed countries. It draws attention to the fact that in replicating the study one must take into account countries that have a smaller psychic distance, such as between Brazil and Uruguay, where perceptions of risk, imperfect information, and cultural barriers may be similar. In addition, it would be interesting to analyze the relationship between the different failure variables regarding the internationalization of technology startups. The attempt of internationalization addressed in this study – although a case failure – can serve as an instructive example for other companies and situations in different countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Agency for Innovation and Technology Transfer (AGITTEC) at the Federal University of Santa Maria for the opportunity to perform the research with the case startup.

References

Antonello, C. S., & Godoy, A. S. 2011. Aprendizagem organizacional no Brasil. Porto Alegre, Brazil: Bookman.

Antonenko, P. D., Lee, B. R., & Kleinheksel, A. J. 2014. Trends in the Crowdfunding of Educational Technology Startups. TechTrends, 58(6): 36–41.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-014-0801-2

ABStartups. 2018. StartupBase. The Brazilian Startups Association (ABStartups). Accessed January 12, 2018:

https://startupbase.abstartups.com.br/

Bardin, L. 2011. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisbon: Edições 70.

Belk, R., Fischer, E., & Kozinets, R. V. 2013. Qualitative Consumer and Marketing Research. London: Sage.

Carneiro, J., & Dib, L. A. 2007. Avaliação comparativa do escopo descritivo e explanatório dos principais modelos de internacionalização de empresas. INTERNEXT – Revista Eletrônica de Negócios Internacionais da ESPM, 2(1): 1–25.

Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. 1991. Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness. The Executive, 5(3): 45–56.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4165021

Creswell, J. W. 2014. Investigação qualitativa e projeto de pesquisa. Tradução de Sandra Mallmann da Rosa (3rd Ed.). Porto Alegre, Brazil: Penso.

Da Rocha, A., Senra, M. W. S., Da Silva, J. F., De Mello, R. D. C., & Alves, L. A. 2015. Building Asymmetric Symbiotic Relationships: International New Ventures and the Multinational Network. Paper presented at the XXXIX Encontro da ANPAD, Belo Horizonte/MG, September 13–16, 2015.

Da Silva, V. A., Scherer, F. L., & Pivetta, N. P. 2016. Influence of Institutional Factors on the Internationalization Process of the Brazilian Industry. Revista Espacios, 37(23): 27.

De Moraes, W. F. A., Leite, Y. V. P., Machado, A. G. C., & Salazar, V. S. 2015. Odebrecht: o estudo das dimensões da internacionalização. Paper presented at the XXXIX Encontro da ANPAD, Belo Horizonte/MG, September 13–16, 2015.

Fleury, A., & Fleury, M. T. L. 2012. Multinacionais brasileiras: competências para a internacionalização. Rio de Janeiro: FGV.

Gitahy, Y. 2010. O que é uma startup? São Paulo: Exame.

Honorato, C. T. 2007. Identificação de competências organzacionais brasileiras no processo de internacionalização e inserção competitiva no mercado global. MBA Dissertation. São Paulo, Brazil: The School of Economics, Business and Accounting, University of São Paulo.

http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/12/12139/tde-30012008-102739/p...

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 1977. The Internationalization Process of the Firm — A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23–32.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490676

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 1993. The Internationalization Process of a Firm: A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitment. In P. Buckey & P. Ghauri, P. (Eds), Internationalization of the Firm: A Reader: 32–44. Londres: Academic Press Limited.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 2009. The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1): 1411–1431.

http://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.24

Johanson, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. 1975. The Internationalization of the Firm — Four Swedish Cases. Journal of Management Studies, 5(1): 305–322.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1975.tb00514.x

Kedia, B. L., & Chhokar, J. S. 1986. An Empirical Investigation of Export Promotion Programs. Columbia Journal of International Business, 21(4): 13–20.

Kohler, T. 2016. Corporate Accelerators: Building Bridges between Corporations and Startups. Business Horizons, 59(1): 347–357.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.01.008

Leonidou, L. C. 1995. Empirical Research on Export Barriers: Review, Assessment and Synthesis. Journal of International Marketing, 3(1): 29–43.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25048577

Leonidou, L. C. 2004. An Analysis of the Barriers Hindering Small Business Export Development. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(3): 279–302.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00112.x

Lopes, F., Silva Filho, R., & Rocha, A. 2007. Proposições Teóricas sobre Modos de Entrada em Novos Mercados caminhos para internacionalização de empresas brasileiras. Porto Alegre, Brazil: Instituto Franco-Brasileiro de Administração de Empresas (IFBAE).

Machado, M. A., & Scorsatto, R. Z. 2005. Obstáculos Enfrentados na Exportação: um Estudo de Caso de Exportadoras Gaúchas de Pedras Preciosas. Paper presented at the Encontro Nacional dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em Administração – XXIX ENANPAD.

Mazon, F. S., Jaeger, M. A., & Kato, H. T. 2010. Percepção das barreiras aos negócios internacionais: aspectos relacionados à internacionalização e expatriação. Perspectiva, 34(126): 33–45.

Melin, L. 1992. Internationalization as a Strategy Process. Jornal de Gestão Estratégica, 13(52): 99–118.

https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130908

Minayo, M. C. S. 2012. Análise qualitativa: teoria, passos e fidedignidade. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 17: 621–626.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012000300007

Minello, I. F., & Scherer, I. B. 2014. The Resilient Characteristics of Entrepreneur Associated with the Business Failure. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 16(38): 228–245.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8077.2014v16n38p228

Moini, A. H. 1997. Barriers Inhibiting Export Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Firms. Journal of Global Marketing, 10(4): 67–93.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J042v10n04_05

Monticelli, J. M., Vasconcellos, S. L., Garrido, I. L., & Calixto, C. V. 2017. Aprendizagem organizacional e teoria neoinstitucional à luz da escola comportamental. Revista Ciências Administrativas, 23(2): 308–321.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5020/2318-0722.23.2.308-321

Morgan, R. E., & Katsikeas, C. S. 1997. Theories of International Trade, Foreign Direct Investment and Firm Internationalization: A Critique. Management Decision, 35(1): 68–78.

https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749710160214

Neubert, M. 2015. Early Internationalisation of High-Tech Firms: Past Accomplishments and Future Directions. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 6(4): 353–369.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTCS.2015.074603

Neubert, M. 2016a. Significance of the Speed of Internationalisation for Born Global Firms – A Multiple Case Study Approach. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 7(1): 66–81.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTCS.2016.076067

Neubert, M. 2016b. How and Why Born Global Firms Differ in Their Speed of Internationalization – A Multiple Case Study Approach. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 7(2): 118–134.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTCS.2016.078168

Neubert, M. 2017. Lean Internationalization: How to Globalize Early and Fast in a Small Economy. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5): 16–22.

http://timreview.ca/article/1073

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. 1994. Toward a Theory of International New Ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1): 45–64.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490193

Reid, S. D. 1981. The Decision-Maker and Export Entry and Expansion. Journal of International Business Studies, 12(2): 101–112.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490581

Rezende, S. F. L. 1999. Expansão Internacional: Impactos da cultura na Escolha do Produto e na Forma de Entrada. In S. B. Rodrigues (Ed.), Competitividade, Alianças Estratégicas e Gerência Internacional. São Paulo: Atlas.

Ries, E. 2011. The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. New York: Crown Business.

Sampieri, R. H., Collado, C. F., & Lucio, M. P. B. 2017. Metodologia de Pesquisa (5th Ed.). Porto Alegre, Brazil: Penso.

Thorstensen, V. 1998. A OMC – Organização Mundial do Comércio e as negociações sobre comércio, meio ambiente e padrões sociais. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 41(2): 29–58.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-73291998000200003

Triviños, A. N. S. 1987. Introdução à pesquisa em ciências sociais: a pesquisa qualitativa em educação. São Paulo: Atlas.

Uner, M. M., Kocak, A., Cavusgil, E., & Cavusgil, S. T. 2013. Do Barriers to Export Vary for Born Globals and Across Stages of Internationalization? An Empirical Inquiry in the Emerging Market of Turkey. International Business Review, 22(5): 800–813.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.12.005

Vozikis, G. S., & Mescon, T. S. 1985. Small Exporters and Stages of Development: An Empirical Study. American Journal of Small Business, 10(1): 49–64.

https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878501000106

Yin, R. K. 2015. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York: The Guilford Press.

Keywords: entrepreneurial, innovation, internationalization, startups, technology